File Hills Indian Residential School

File Hills Indian Residential School

The File Hills Indian Residential School (1889 – 1949) was run by the Presbyterian Church from its opening in 1889 until the United Church of Canada took over in 1925. The school was located north of Balcarres on the boundary of the Okanese reserve, and adjacent to the File Hills Agency Indian reserves on Treaty 4 land. The school could initially accommodate 25 children. By 1948 enrollment was up to 100 students, an overcrowded situation. The plumbing was deemed unsanitary, and the building a fire hazard. The school closed in 1949. Children close by attended day school, while others were sent to Brandon or Portage la Prairie residential schools.

See http://vitacollections.ca/sixnationsarchive/3180398/image/2729094 News clipping Searching for Ways to Heal

Douglas Bear’s illness and his parent’s struggle to bring him home

Letter from a Chief Ben Pasqua complaining that boys were tending sheep and not learning

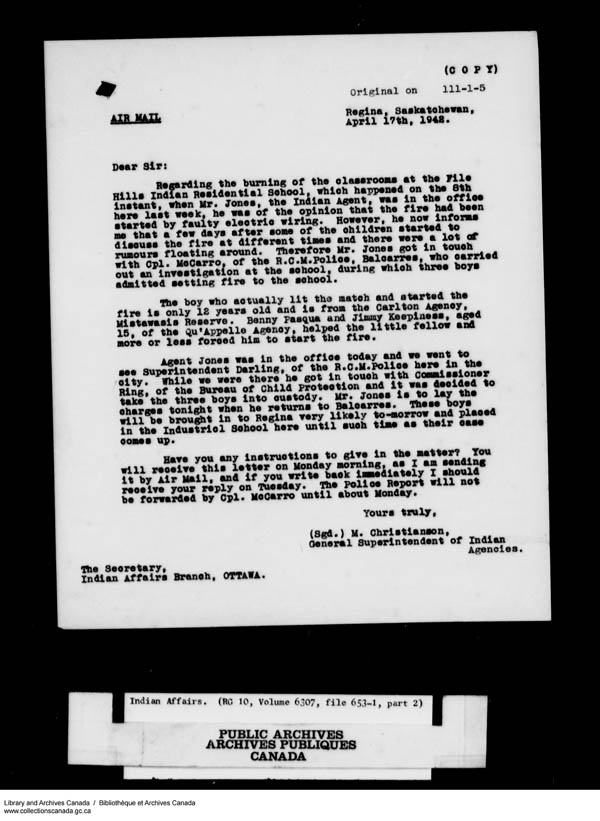

Classroom destroyed by deliberately set fire. Five boys charged.

Survivor Stories

Melvina McNabb was seven years old when she was enrolled in the File Hills school, and “I couldn’t talk a word of English. I talked Cree and I was abused for that, hit, and made to try to talk English. I would listen to the other little girls and that’s how I picked up English. It was very hard for me because I didn’t know why these staff were hitting me.”6 (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, p. 623)

Melvina McNabb suffered a … injury at the File Hills school in the 1930s. “I was working in the laundry with no supervision. This was my first time working there. The girls were all scrubbing. No one was watching me. I stepped on this lever, this extractor that dries clothes. It was going slow but it still caught my arm.” She was hospitalized and left with a twenty-five-centimetre scar on her arm.168 (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, p. 349)

Students had differing memories of the role that religious training played in the schools. For some, it was their greatest legacy. Elsie Ross, who attended the File Hills, Saskatchewan, school during this period, recalled, “We did very good ground work in religion and Christian belief. Mr. Rhodes was our instructor and principal. He was very good at teaching us religion. I am eternally grateful for that because I have a firm standing in Christian beliefs to this day. That was good.”120 Bernard Pinay, another File Hills student, felt that “religion was never driven to us. If we wanted to go to church, usually they had it on a Sunday, we could make an excuse and they wouldn’t say nothing.”121 (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, pp. 318-319)

Pauline Creeley had similar school memories about File Hills, Saskatchewan: “The worst part I used to have to scrub the cement floor every day, sometimes twice a day. It was very hard on the knees. In those days there was no such things as kneeling pads or mops with long handles. I used to kneel on my hands and they would get very sore.”31

For Alice Star Blanket, the laundry room at File Hills was the one place that I dreaded to work in because it was a place where you were required to work hard, like hard labour. They kept us very busy here; there was washing of lots of clothes and bed clothes to be laundered, hanging them up outside, folding them up and carrying these clothes and bed clothes to the rooms upstairs. There were big machines in the laundry room that we had to man and they were big noisy things like they have in the hospitals, big washers and dryers.32 (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, p. 335)

Many students recalled being overworked. In an interview, Bernard Pinay said he had nothing against File Hills School. The only thing is I didn’t get much schooling because I spent a lot of time working on the farm. I still think the FHIRS [File Hills Indian Residential School] owes me about five or six years of wages, working on the farm there. Our supervisor, he was the one that was supposed to do that but he didn’t, I did.102

Of his years at File Hills, Alvin Stonechild said:

At our young age, we worked hard, a great deal of manual labour was carried out by we boys at our young age, like working in the gardens. We tended to rows of vegetables so the children could eat vegetables for a good part of the school term. We stored these vegetables in root cellars which we cleaned out from time to time. I can say that I had six years of work experience even though we were driven like slaves. One could term this kind of work as child labour.103 (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, p. 343)

In keeping with a United Church policy opposing the cadet program in schools, the church disbanded its cadet corps at the File Hills, Saskatchewan, school in 1931. Russell Ferrier, the superintendent of Indian Education, asked the principal to reconsider his decision. Ferrier thought the church policy of opposition to cadet training was limited to the public school system. “Residential schools,” he argued, constituted “another proposition, and I believe you will find that a cadet corps at an Indian institution will assist greatly with both the esprit de corps and the discipline.”145 Principal F. Rhodes responded that military training was not popular with the boys. He said there was already more military discipline in a residential school than in a public school, as File Hills boys were “constantly under supervision.” He went on to remind Ferrier that the school had no facility for drills. It was necessary to remove the table and the benches from the dining room in order to hold cadet drills during the winter. He concluded by pointing out that the school had made several requests in the past for funding for a gymnasium or a playroom, but, to date, nothing had been done.146 (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, pp. 368 -369)

Former File Hills, Saskatchewan, student Ivy Koochicum chafed at the inequality she saw: “They got the cream and we got skim milk.”74 (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, p. 498)

On one occasion, the students at the File Hills school came across barrels of apples that were meant for the staff. Over time, the students worked their way through the apples. When the deed was discovered, they were strapped and sent to bed without a meal.105 In fair weather, the boys at the school would trap gophers and roast them over open fires to supplement their diets.106 (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, p. 505)

Pauline Creeley, a former File Hills student, “used to steal bread for the boys; put them in the milk cans. I would watch them eating the bread as they made their way to the barns. I didn’t care if I got caught but I never got caught.”111 (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, p. 506)

Some students remembered the daily clothing as being uncomfortable. Ivy Koochicum, who attended the File Hills school in Saskatchewan in the 1920s, said, “We wore slips and bras made out of flour sacks. We had loose dresses; they used to make them; they were just plain with a belt. Then we wore black stockings with boots. The boots were ill-fitting in that they were very tight.”15

Pauline Creeley attended File Hills in the 1930s. She recalled:

Our boots were not warm. We only had one pair of cotton stockings. Our coats were made of heavy melton [a heavy woollen fabric], which were warm. We had mitts. I cannot remember if we had sweaters. We had big bloomers. Our uniforms were made like a jumper with a dress underneath. They were not warm. On Sundays, we had a black-and-white outfit, midi and a jumper, sleeveless dress with a white blouse under. That was our Sunday best which we wore to church only.16 (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, p. 513)

It was not uncommon for runaways to have their hair cut short or shaved off, in addition to being strapped. Alice Star Blanket attended the File Hills, Saskatchewan, school in the 1930s. She recalled that runaways at that school were “punished with a strap, shave their hair off, get bald heads.”45 (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, p. 525)

When a boy was caught in the act of attempting to burn down the File Hills school in 1932, he was immediately strapped on his hands. The principal wished to send him to the Regina Detention Home. The local Indian Affairs inspector, W. Murison, reported, “This boy is of very low mentality; as a matter of fact he cannot be considered normal.” The Indian agent favoured taking a lenient approach to the case. Murison said he feared that directly discharging the boy into the care of his parents would “act as an incentive to other boys to attempt the same thing in order to bring about their discharge.” Therefore, he suggested transferring him to another school, and, from there, discharging him to his home. Officials were unwilling to take the correct step directly and immediately—in this case, returning a boy to his family when the school was incapable of caring for him—for fear of appearing weak or vulnerable. Among the reasons why Inspector Murison opposed having the boy sent to the Regina Detention Home was the fact that the case would first have to be brought before a juvenile court. This would have involved an expense that he knew Indian Affairs was “anxious to avoid.”87 (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, p. 529)

The residential schools had no resources to accommodate students with disabilities. Such students might find themselves subject to bullying and discriminatory treatment from both staff and students. One such student attempted to kill himself at the File Hills school in 1939. After interviewing him, the director of the Psychopathic Department of the Regina General Hospital, Dr. O. E. Rothwell, reported, “He is undoubtedly deaf and has considerable difficulty in the school classroom, and as a result of this he claims that the teacher would get out of patience with him at times and ‘Boxed his ears,’ I believe he said. He is quite emotional and cried when telling about it.” Rothwell wrote that the boy was teased by the older boys because of his disability, adding that they also would “impose upon him.” He recommended that the boy be sent to a different school.15 Dr. A. B. Simes, the medical superintendent of the Qu’ Appelle Indian Health Unit, concluded that the boy was not intent on taking his own life, but rather that “he wished to stir up dissatisfaction against the school and staff, with the hope that he would be discharged.”16 In the end, the boy was returned to the File Hills school.17(The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, pp. 573-574)

Of her time at the File Hills, Saskatchewan, school, Millicent Stonechild stressed the way that the children were sustained by friendships.

When we are getting discouraged and in need of healing, we must remember those people who helped us. In particular, I think of my friend, Mabel Star. There was much laughter amongst the children, a sustaining factor. We also comforted one another from the loneliness. In September, we took turns crying. In spite of some of the ‘bullying’ that went on, we established life long friendships.3

As her memories suggest, there were also bullies at the schools. The groups the students formed to protect themselves might turn on other smaller students, or on students who did not fit in with them. (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, p. 571)

Melvina McNabb recalled how, in the 1930s, she and friends defended themselves against a group of bullies at the File Hills school. They were these ladies who were mean to us. We had to do what they asked of us or we would get punished. For instance, there was this one lady who was the same age as I who set the fire or water hose on us in our beds. We were all soaking wet. We couldn’t tell on her because we would get pounded by her bigger sisters. That was abuse in itself. As we got older, we made a plan all of us, fifteen year olds. All right now, who’s going to do the fighting? As usual, I was chosen to be the fighter. We made a big circle and we put this lady in the middle of the circle. Boy! Did we ever lambaste her! She’s not going to boss us anymore. That’s how that part stopped. She quit.12 (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, p. 573)

Ivy Koochicum, who attended the File Hills school in the 1920s, said that decades after she left, she still had nightmares about life in the school. “The part I would like to forget about is how cruelly we were treated. We were treated cruelly not only by the staff but by the pupils. There was name calling and fighting. There was one family that was very mean. There was nothing we could do. We just took it.”13 (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, p. 573)

Charlie Bigknife recalled his first day at the File Hills, Saskatchewan, school:

First thing I knew, I was ushered into a room, which they called the playroom, I didn’t know at the time. The farm instructor whose name was Mr. Redgrave and who was an old sergeant from the First World War came in with a sheep’s shear and cut my 4 braids off and threw them on the floor. After a while along came a young boy rolling a horse clippers into the room and that horse clippers bounced over my head and gave me a bald head. After he got through, he said, “Now you are no longer an Indian” and he gave me a slap on the head.4 (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, p. 599)

…the loss of Aboriginal language skills was reported as a sign of progress. In 1893, school inspector T. P. Wadsworth wrote that, according to the principal of the File Hills school in what is now Saskatchewan, the children spoke only English, even at play, and that “one little fellow has forgotten almost entirely his native dialect.” In addition, none of the students had wished to attend “the sun dance held on the reserve near the school.”39 (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, p. 621)

Bernard Pinay, who attended the File Hills school in the 1930s, said, “I never had a culture before I went to school. I didn’t have any for them to take away.”76 At the school, there was no tolerance for attempts to discover or revive cultural practices. “When we were in boarding school we never tried to do any of the Old Indian Ways because the staff and the school were really dead against it. There was nothing we could do about it; some tried but they always got hell. So I can’t really name what the ceremonies were because we really never had any.”77 It was only after he left the school that he was exposed to, and participated in, Aboriginal spiritual practices.78 (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, p. 640)

Photo Gallery

B’yauling Toni’s Moccasins of Remembrance Bike Tour at Okanese First Nation August 5, 2021

https://my-site-102728-103753.square.site/byauling-toni