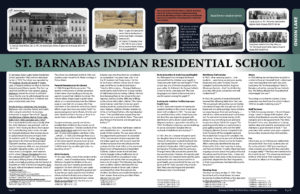

St. Barnabas Indian Residential School | Onion Lake

St. Barnabas Indian Residential School | Onion Lake

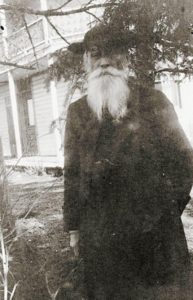

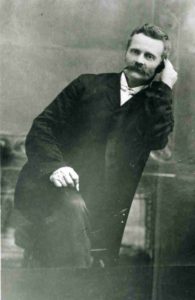

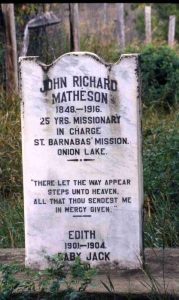

St. Barnabas (Onion Lake) Indian Residential School opened in 1892 and was destroyed by fire in 1943. The school was operated by the Anglican Church of Canada at Onion Lake, (Treaty 6) on what is now the Saskatchewan/Alberta border. The then lay catechist (and fluent Cree speaker) John R. Matheson started the school in a Mission house that he and his wife had paid for and constructed. It initially held 10 children both First Nation and settler who attended voluntarily. The school was built after Rev. Henry Ellis became principal in 1917. The school was destroyed by fire in 1943 and students were moved to St. Alban’s College in Prince Albert.

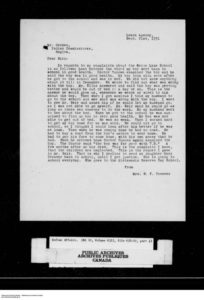

Mrs. Dreaver’s letter regarding the death of her son at St. Barnabas School:

September 21, 1931: “Last October the third my boy went back to school in good health. Doctor Duncan examined the boy and he said the boy was in good health. My boy took sick soon after he got to the school and was in bed. We did not know anything about it till in December. We wrote to find out what was wrong with the boy. Mr. Ellis answered and said the boy was getting better and would be out of bed in a day or so. This is the answer he would give us, whenever we wrote or wired to him about the boy. Then when I got anxious I told my husband to go to the school and see what was wrong with the boy… When he got to the school he was surprised to find my boy in very poor health. My boy was not able to get out of bed. He was so weak. Then I worked hard to get my boy home for he was sick. He could not go to school, so I thought I could look after him better if he was at home. Then when he was coming home he had no coat. He had to buy a coat from the boy’s matron to wear home…When he arrived home Doctor Duncan again examined the boy. The Doctor said, ‘the boy was far gone with T.B.’ A few months after my boy died. This is the complaint I have that the children are neglected. … This is why I decline to send my daughter Mary Dreaver back to school, until I get justice. She is going to school everyday [sic]. She goes to the Mistawasis Reserve Day School.”

________________

Dreavers of Mistawasis (see Saskatchewan Indian, December 05, 1972, “A Saga of Service“) Chief Joe Dreaver (see Saskatchewan Indian, October 1970, “Chief Joe Dreaver: Indian Statesman, Patriot And Soldier” By: Sol Sanderson) was son of Chief George Dreaver and the grandson of Chief Mistawasis a signee of Treaty #6. (see http://www.creenationsheritagecentre.ca/chief-mistawasis.html). Saskatchewan Indian

________________

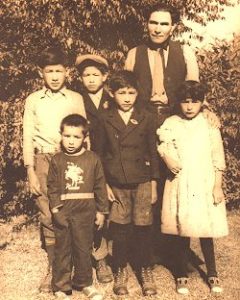

An Intergenerational Story by Alvina Dreaver Why My Dad Went to Jail

I remember a way back in years, about fifty years ago. I was about five years old at that time. There was flu going around. A lot of children died.

Three of my sisters died within two days. Nancy and Gladys died at home on the Muskoday Reserve. Beatrice died at the Onion Lake residential school. The news of her death did not reach my parents for about two weeks. Beatrice was buried at Onion Lake. My dad wanted to build coffins for the burial of my two other sisters but he needed some lumber. To get the lumber he needed, he wanted to sell one of his steers. To sell the steer he had to get a permit from Mr. Simpson, the farm instructor. But the farm instructor refused to give him a permit.

My dad went ahead and sold one of the steers anyway to a farmer in the Birch Hills district. He then bought the lumber and white material he needed to make the coffins. He made the coffins and buried my sisters.

About a month later, the RCMP came to our home. Mr. Simpson was with them. He showed the police where we lived. They took my dad away because he had sold a steer without a permit. My dad spent three months in jail.

(As told to Shirley Bear, Alvina Dreaver is the daughter of Gilbert James Bear, and his wife Kathleen Maude, both deceased)

__________________________________________

Annie Bird was “secured” and taken to Onion Lake St. Barnabas IRS in 1924 at 14 years of age. Annie married Edward Ahenakew (nephew of Canon Rev. Edward Ahenakew) and they became the parents of eight children including Freda Ahenakew of Ahtahkakohp First Nation who after moving to Prince Albert resided at St. Alban’s, while attending Prince Albert Collegiate Institute (PACI). In her final year at PACI she married Harold Greyeyes.

Annie Bird was “secured” and taken to Onion Lake St. Barnabas IRS in 1924 at 14 years of age. Annie married Edward Ahenakew (nephew of Canon Rev. Edward Ahenakew) and they became the parents of eight children including Freda Ahenakew of Ahtahkakohp First Nation who after moving to Prince Albert resided at St. Alban’s, while attending Prince Albert Collegiate Institute (PACI). In her final year at PACI she married Harold Greyeyes.

______________________________________

Fires in 1928 and 1943

_____________________________________

Survivor Stories

Allen Sapp was born in 1928 on the Red Pheasant Reserve in Saskatchewan. He spent several years at the Anglican boarding school at Onion Lake. He described it as a lonely and unhappy experience.

“No one ever abused me physically or sexually but the way we were disciplined was not like home. We were forbidden to speak Cree—the teachers and everyone connected to the school spoke English—but Cree was the only language I knew.

If we were caught speaking Cree to one another we would be punished. One particular day I was caught speaking Cree to one of my classmates and told that I would have to go up and remain in my room. That afternoon there was a cowboy movie showing in town and I so wanted to go to that movie. I sat in my room and cried.”68 (Vol. 1, p. 624)

The Life and Art of Allen Sapp

_______________________________________

Once, at the Anglican school in Onion Lake, Ula Hotonami was strapped by the laundry superintendent for joking with a student in the hallway. The principal encountered her shortly afterwards and asked her why she was crying. When she explained what happened, the principal told her to go into his office.

And he put me in his office, and he had told me, “You wait there,” and so I, I waited in his office. We were never allowed in his office, like, not, and he, he went down to the laundry room, and must have went and talked to her. Within two weeks she was gone, anyway. So, I don’t know. His name was Mr. Card and that. And so he told me, “You can miss school ’til the swelling goes down.” So, I was thinking what’s going on here, like, you know, why, why do I have to miss school now? I can’t go to work. I can’t go to school. And so I asked him, “Well, what am I gonna do? Like, I have to go to school and that.” And he told me, “Well just, you, you can’t do anything, anyway. You can’t hold anything in your hand,” he said, “they’re all swollen.” Like, my hand was just puffed up, like, from the strapping that I got.531 (SS. p. 150)

_________________________________________

In 1923, the parents of Edward B., a student at the Anglican school at Onion Lake, Saskatchewan, received the following letter: “We are going to tell you how we are treated. I am always hungry. We only get two slice of bread and one plate porridge. Seven children ran away because there [sic] are hungry, two from Saddle and one from Frog Lake, and two from Snake Plain, 3 girls and 4 boys because are always hungry too. I sold all my clothes away because I am hungry too. Try and send me some money, $2.50, please to buy something to eat and send me pictures those I left in the wagon.”120

The letter ended up in the hands of F. C. Mears, a parliamentary press gallery reporter, who forwarded it to Deputy Minister Duncan Campbell Scott. He brushed off the complaint and said the student had “no cause for complaint.” He also wrote, “Ninety-nine per cent of the Indian children at these schools are too fat.”121 Indian Affairs eventually identified the boy and informed his father that “your boy is being well fed and clothed.”122 In reality, there had been ongoing concerns about the quality of food at the school, and Scott knew that. Just two years earlier, school inspector Sibbald had reported negatively on the quality of the bread and the fact that the children had no milk to drink. A follow-up report by Indian agent L. Turner had concluded that, although the food was adequate, “there was nothing to drink upon the tables.” He recommended that the principal be instructed that “these conditions must be improved.”123 Scott himself had issued instructions that the food at the school be improved.124 It does not appear that a news story on the issue was ever published, despite the fact that the parents, or their acquaintances, had taken the issue to the press. (Vol. 1, p. 507)

__________________________

Michelle Good author of Five Little Indians:

Toronto Star: “When I was still quite little, my mother told me of her friend, Lily, a fellow inmate at the St. Barnabas Residential School in Onion Lake, Saskatchewan. This was not the story one would expect about school chums. No, this was the story of how a little girl, taken without consent from her home and community, hemorrhaged to death from tuberculosis while her little classmates stood by helpless.” Michelle Good_ ‘Imagine the terror of the children’ — ‘Non-Indigenous Canada, this is the time to raise your voices’

Toronto Star: “When I was still quite little, my mother told me of her friend, Lily, a fellow inmate at the St. Barnabas Residential School in Onion Lake, Saskatchewan. This was not the story one would expect about school chums. No, this was the story of how a little girl, taken without consent from her home and community, hemorrhaged to death from tuberculosis while her little classmates stood by helpless.” Michelle Good_ ‘Imagine the terror of the children’ — ‘Non-Indigenous Canada, this is the time to raise your voices’

————-

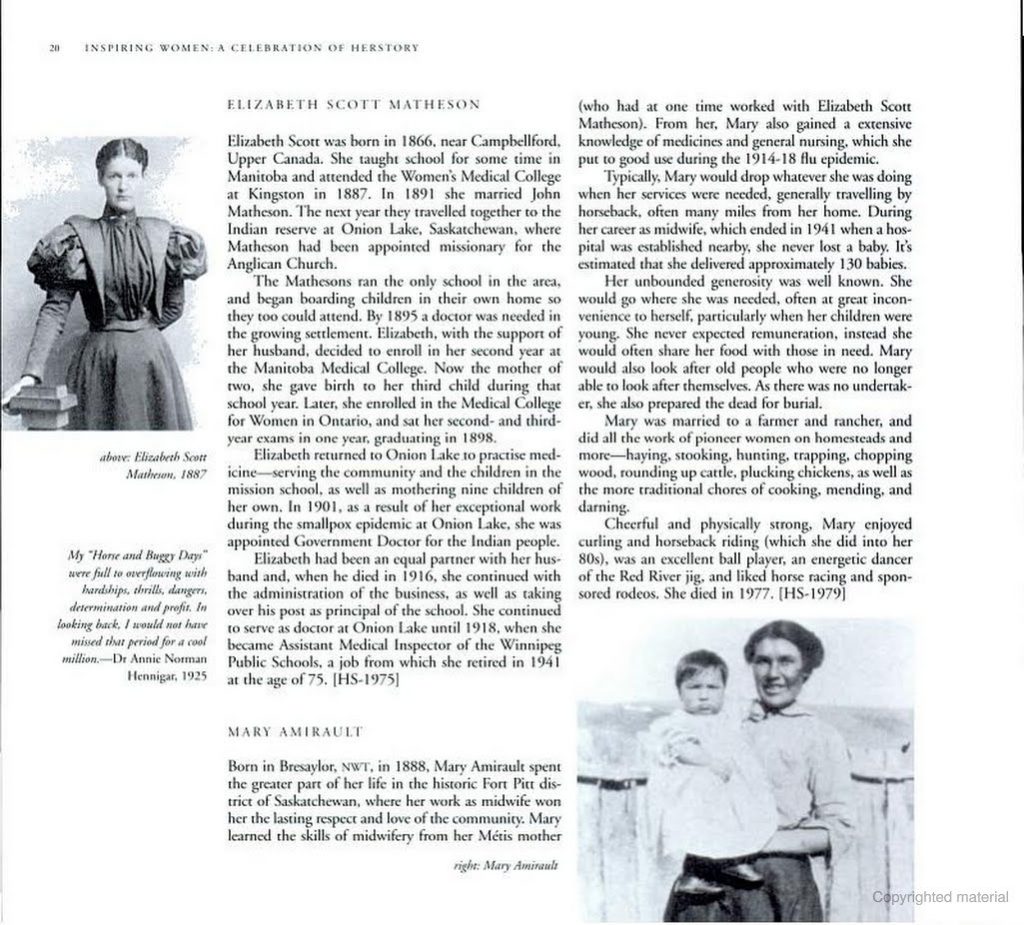

Matheson Family – Four members buried at Onion Lake

See The Doctor Rode Side-Saddle: The Remarkable Story of Elizabeth Matheson, Frontier Doctor and Medicine Woman By Ruth M. Buck https://uofrpress.ca/Books/T/The-Doctor-Rode-Side-Saddle