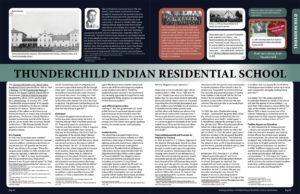

Thunderchild (St. Henri) Indian Residential School | Delmas

Thunderchild (St. Henri) Indian Residential School | Delmas

The Thunderchild (Delmas/St. Henri) Indian Residential School operated from 1901 to 1948 at what became Delmas, outside and west of the Thunderchild Reserve on Treaty 6 land. In January 1901, Chief Thunderchild wrote on behalf of his people to protest the building of a Roman Catholic school on his reserve. “We feel that as a majority of the Indians on the Reserve are Protestant there is no reason why it should be placed here …The Roman Catholic Mission is situated immediately outside of the Reserve and we see no reason why the school should not be there…”1 The Roman Catholic Church (RCC) agreed to build the school at their mission property instead. The RCC Oblate missionaries (Oblates of Mary Immaculate) operated the school, which was founded by Fr. Henri Delmas. Fr. Delmas worked with the Sainte-Angèle mission but the name was changed to Delmas in 1905.

The railway was built through Thunderchild Reserve in 1904, which brought an invasion of white settlers. In 1909 and 1910 Thunderchild and another Reserve were relocated by Ottawa (Source). This source claims that Father Delmas was asked by the inhabitants of Thunderchild and Moosomin Reserves to intervene on their behalf with the federal government because they wanted to relocate. However, Lawyer Eleanore Sunchild says, “the First Nation was forcibly relocated in the early 1900s due to a vote achieved by manufactured consent.” (Source).

____________________________________________________

Sister’s Refusal to Include Farming in

Curriculum

In 1929, the Acting Principal, a Sister, advised the federal government that she was strongly opposed to farming instruction and that parents were too. They didn’t want their children working on a farm. In 1934, in response to the government’s further inquiry on the issue, Father A. Naessens explained to Deputy Minister Scott that at Delmas, the Sisters were practically running the Institution, and “they have been frequently told about the wishes of the Department with regards the training of the older boys in farming; but they seem to have objections towards complying with these instructions in that respect.” However, if directed to do so, the Sisters would arrange for farming to be taught. Scott responded that the principal ought to have control of his school, and that a prairie school that did not provide instruction in farming was not likely to “remain a factor in our educational programme.” The school did end up with a small farm operation with 16 hectares under cultivation.

__________________________

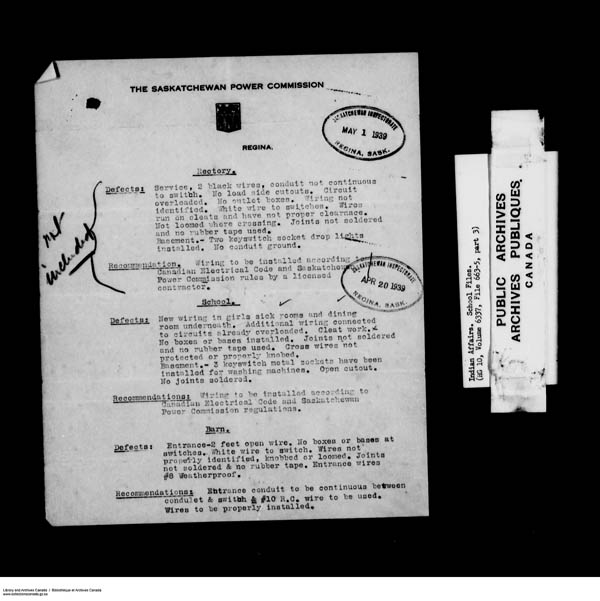

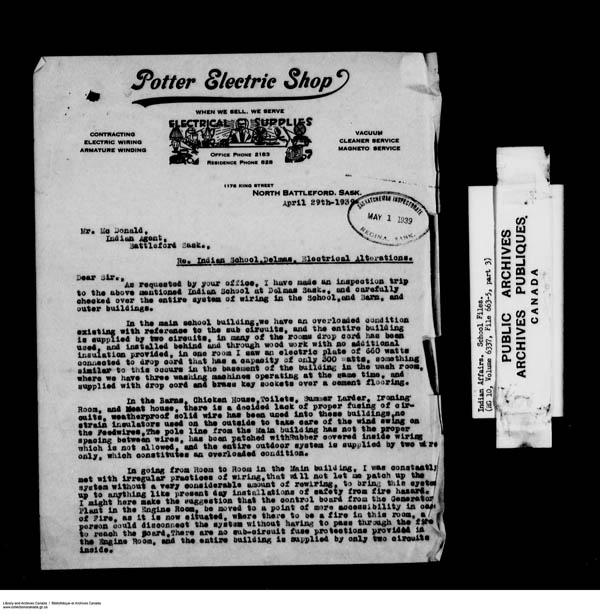

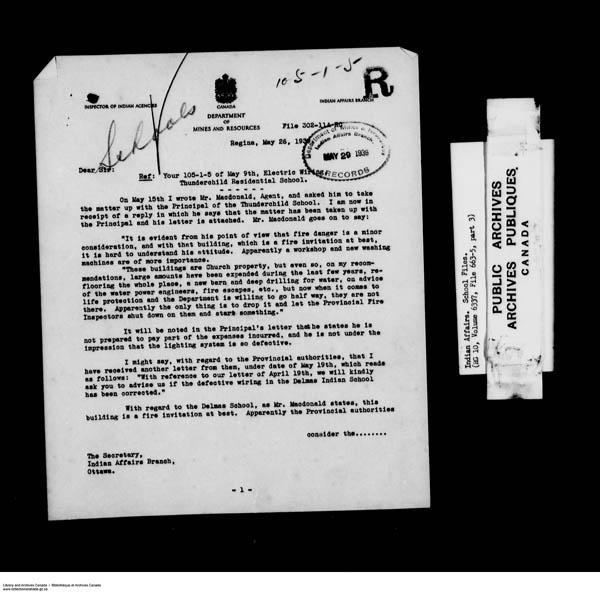

Electrical/Wiring issues in school reported in 1939

In 1939, the electrical wiring was reported as defective and was

repaired.

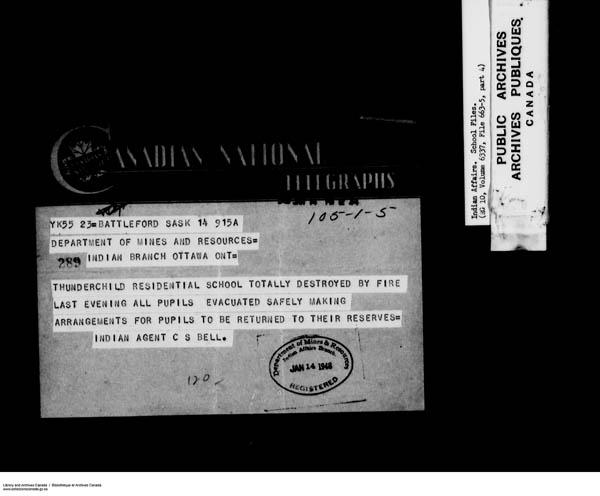

Fire Destroys School in 1940 (Same year All Saints in Lac La Ronge burned)

Four boys suspected of starting the fire, but not enough evidence to lay charges.In 1940, R. A. Hoey recommended that the government close [the] school because it was “in poor state of repair.” (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, pp. 463-464) In 1948, the school was destroyed by fire and was not rebuilt. Several boys were investigated, and two were suspected of setting the fire though there wasn’t enough evidence to convict them. Several boys had previously made threats to burn down the school. According to a 1993 account of a former student, “the fire was set by four boys who warned the rest of the boys in advance. The girls were not told, because the ‘girls’ dormitories were on the other side and so they had lots of time to get out.’”

_______________________________________________________

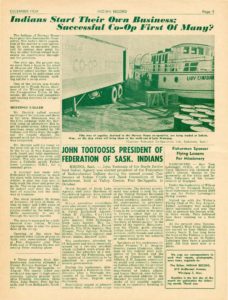

John Tootoosis, a Cree leader of great renown attended the Delmas Residential School in Saskatchewan beginning in 1912. Tootoosis recalls the day “the black-garbed priest” came to talk to his parents, and his discovery that his father intended to send John and his brother to the boarding school at Delmas to learn “to read, write and count and to be able to speak the language of the white men,” skills he had often needed. His father wanted a better future for his children. His mother, however, “looked on silently.” After four years, Tootoosis was frustrated because he wanted to learn as his father had wished, but his days were filled with religious instruction and physical labour. He decided to educate himself “reading and committing to memory everything he could lay his hands on, in English and in Cree”(109) (Source: Scott, J. S. (2004). Residential schools and Native Canadian writers. In P. H. Marsden & G. V. Davis (Eds.), Towards a transcultural future: Literature and human rights in a ‘post-colonial world. ASNEL Papers 8 (pp. 236-237). New York, NY: Rodopi.)

From his time at residential school, Tootoosis recalled that sometimes some children did not want to eat … [because] there were these big iron pots on the stove, that’s where they boiled clothes before washing … This one spring the meat was probably thawing and about to get bad. Didn’t they go and boil the meat in these pots and that’s what they tried to feed us. It was very difficult to eat the food (as cited in Goodwill and Sluman, 1984:100). Source: Métis History and Experience and Residential Schools in Canada, p. 133

John Tootoosis said that for Aboriginal children, the residential school experience was “like being put between two walls in a room and left hanging in the middle. On one side are all the things he learned from his people and their way of life that was being wiped out, and on the other side are the white man’s ways which he could never fully understand since he never had the right amount of education and could not be part of it. There he is, hanging in the middle of two cultures and he is not a white man and he is not an Indian.14” (Canada’s Residential Schools: The History, Part 1, Origins to 1930 p. 214)

In 1912, twelve-year-old John Tootoosis Jr. and his younger brother Tom were herding their family’s sheep on the Poundmaker Reserve in Saskatchewan, when they caught sight of a wagon outside their parents’ home. A priest was in earnest discussion with their father, who was far from impressed by residential schooling, though he could see the value in formal education. Former students, alienated from their families and their traditions, were already referred to on the reserve as “the crazy schoolers.” In the end, their father’s concern that the boys learn to read, write, and figure won out. He told them to eat a quick meal and put on their warm clothing; they were being sent forty kilometres away to the Delmas boarding school (also called the Thunderchild school).135 The boys enjoyed the wagon ride, but were surprised and overwhelmed by the nuns who met them on their arrival. In coming days, they discovered they would be punished for speaking Cree and risked further punishments for making mistakes in English. Many students retreated into themselves, but John Tootoosis became adversarial.

In his mind, there was too much religion, too much work, a limited and inedible diet, and not enough education. He survived, in part because of the time he spent with his family in the summers. But, just when he was looking forward to further education, he was told that, at age sixteen, the government was not going to pay for any additional education for him. He returned to the reserve and, with his father’s support, slowly began to work his way back into the life of the community.136 After leaving residential school, John discovered to his frustration that his English was not serviceable. Having been taught by native French speakers at the Delmas school, he could not understand the English that was spoken in Prairie communities, and his English was burdened with both a Cree and a French accent.137 In language strikingly similar to that of Edward Ahenakew, Tootoosis gave an early critique of the residential school legacy. He said that when an Indian comes out of these places it is like being put between two walls in a room and left hanging in the middle. On one side are all the things he learned from his people and their way of life that was being wiped out, and on the other side are the whiteman’s ways which he could never fully understand since he never had the right amount of education and could not be part of it. There he is, hanging in the middle of two cultures and he is not a whiteman and he is not an Indian. They washed away practically everything from our minds, all the things an Indian needed to help himself, to think the way a human person should in order to survive.138 (Extracted from Canada’s Residential Schools: The History, Part 1, Origins to 1930, p. 190)

_________________________________

Solomon Pooyak observed, “All we ever got was religion, religion, religion. I can still fall on my knees at seventy-two years of age and not hurt myself because of the training and conditioning I got at Delmas.” (Source: They came for the Children, p. 26)

_________________________________

Henry Beaudry, originally of Poundmaker First Nation and great grandson of Chief Poundmaker, was born in 1921 and was a former student of Delmas Indian Residential School. Video below documents Henry’s life story. Henry passed away in 2016.

In the video, Henry Beaudry describes his experience as an imprisoned soldier, and illustrates the bravery and contributions of First Nations soldiers in the Second World War.

Theresa Sapp

The night the residential school burned to the ground — and the students cheered. CBC Story