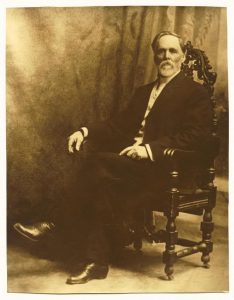

Reverend Dr. Hugh McKay

Reverend Dr. Hugh McKay was principal of Round Lake Indian Residential School from 1884 to 1921. The school had started out as a one-room log cabin on the Qu’Appelle River in 1884 and had closed due to the Northwest Resistance of 1885. By 1888, Mckay had expanded the original one-room log cabin school to accommodate a capacity for 50 students and had applied for funding from the government. (NCTR Report Volume 1, Part 1, p. 607)

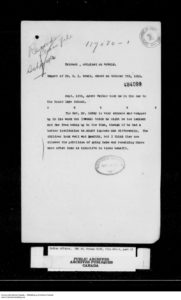

In a report dated October 7th 1915, Indian Affairs medical official Dr. O. Grain complains that though the students at the Round Lake, are progressing, they were “allowed the privilege of going home and remaining there more often than is inductive to their benefit.” Principal McKay was then reminded by S. Stewart, assistant secretary, that students at that school were limited to “one months [sic] holidays each summer and they should not be allowed to go home at other times during the year.” (Indian Affairs, School Files, RG10, Vol 6332, File 661-1, part1)

Agent Taylor then reported in his inspection done January 31, 1916, that “Girls clean and fairly well dressed. Boys hair very long and not too tidy or clean. Conditions at this school are not good. The staff appear to be pulling against the Principal. I asked Principal why children were not in school. He said he had told the parents if they did not send their children he would have to close the school. This don’t seem good enough. It has been very cold weather, but at least most of the children could have been got in without any hardship.” At the time of his visit, there were only 14 boys and 11 girls present. (Indian Affairs, School Files, RG10, Vol 6332, File 661-1, part1)

Much to the annoyance of the local Indian Agent and other DIA officials, McKay took a flexible approach toward attendance. In addition to a month’s vacation in July and time at Christmas, he frequently granted leaves to children so they could help their parents during planting and haying, and he let them visit their homes whenever their parents came for them. The Indian Agent complained that on any given day as many as half the children were absent. “I go to a great deal of Trouble getting the Children in and Mr. McKay lets them go every time Parents come for them,” he wrote in 1917.

During McKay’s lengthy tenure as principal (1884–192[1]), boys were expected to work at least two hours doing manual labour and were paid ten cents an hour for additional work. “A boy who can drive a team may find lucrative employment on the farm, 10 cents an hour is allowed, and thus the older boys may prepare to go out on their own farms with a good outfit when 18 years of age,” McKay reported in 1911.[12] Farmers in the vicinity would also hire boys as help. Girls had the jobs of cooking, sewing, and cleaning, as well as some dairy work: “The older girls can manage a dairy and make butter and loaf bread; they are all taught to sew, knit, use the sewing machine, cut out and make dresses and garments, can make boys’ clothing, moccasins, also do patching, quilting, darning and fancy work.”

(From http://thechildrenremembered.ca/school-locations/round-lake/)

In June 1919, a group of older boys, believed to be former students of the Qu’Appelle and Round Lake schools in Saskatchewan, were caught going into the girls’ dormitory of the Round Lake school. According to the Mounted Police officer called in to investigate the incidents, “From what I can see the girls are trying to protect these boys, and it is a hard job to get much information from them.”59 In response, the school principal, H. McKay, “secured the windows and fanlights by nailing on lumber, had padlocks put on the doors and other things that I thought would make the sleeping rooms secure.” There was not enough evidence to prosecute the boys, but they continued to remain in the vicinity of the school. McKay thought of having one of them prosecuted but refrained because “he is one of my boys, and so much about him that I admire, his music, his song, his free-hand drawing, his aable and seeming kind disposition, I feel surely there is some other way beside having him placed behind the bars.”60 Indian Commissioner W. M. Graham was not impressed with McKay’s leniency, saying it demonstrated that the “supervision of the school is not what it should be.” He requested that the Mounted Police issue warnings to the boys suspected of breaking into the school.61(Vol.1, Part 1, p. 652)

Hugh McKay, the superintendent of Presbyterian work among Aboriginal people, concluded that Aboriginal people were “a people that is becoming extinct, a poor people suffering for want of the necessaries of life and dying without any sure hope for the life to come.”19 McKay criticized the federal government for failing to implement its Treaty promises and for failing to alleviate the hunger crisis on the Prairies.20 (Vol. 1, Part 1, p 679)

Go back to Round Lake Indian Residential School supplementary pages

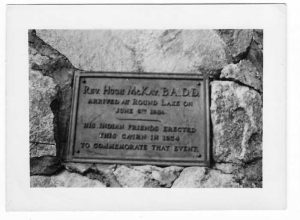

![Mrs. McKay, and nephew of the late Rev. McKay on the occasion of the unveiling of the cairn erected in memory of Rev. Hugh McKay, missionary to the Indians and former principal of Round Lake Residential School] 93.049 P1169](http://www2.uregina.ca/education/news/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/0c9f813e809c619f29c0126f52d73945-187x300.jpg)