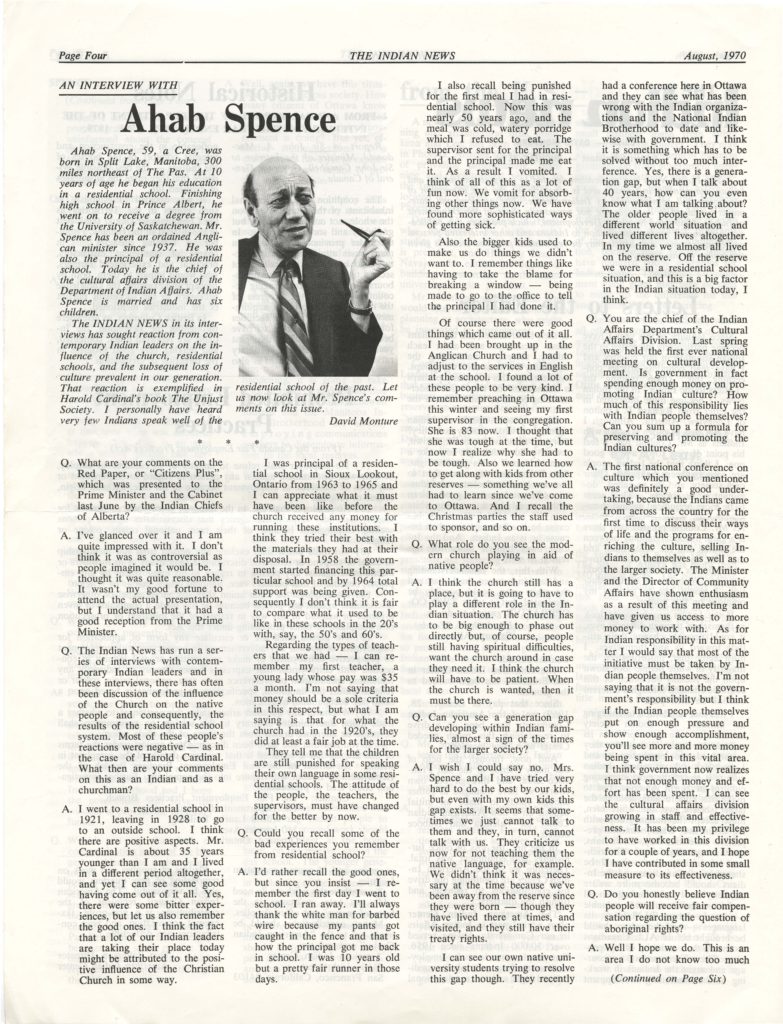

Prince Albert (All Saints) Indian Residential School

Prince Albert (All Saints) Indian Residential School

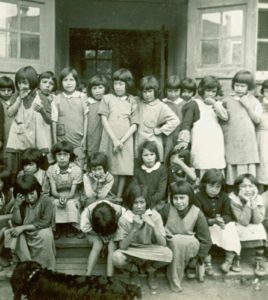

Prince Albert Indian Residential School was an amalgamation of St. Alban’s Indian Residential School and All Saints (Lac La Ronge) Indian Residential School. It was intended to be a temporary solution but ended up operating for 50 years.

Prince Albert Indian Residential School was an amalgamation of St. Alban’s Indian Residential School and All Saints (Lac La Ronge) Indian Residential School. It was intended to be a temporary solution but ended up operating for 50 years.

St. Alban’s Indian Residential School in Prince Albert (Treaty 6), managed by the Anglican Church of Canada, was a replacement school for students from St. Barnabas Indian Residential School (Onion Lake) after it was destroyed by fire in 1943. The girls were quartered at St. Alban’s and the boys at the military camp (All Saints). In 1951, all St. Alban’s students were moved to All Saints in Prince Albert, which was officially named Prince Albert Indian Residential School in 1953.

The Lac La Ronge (All Saints) Indian Residential School (1907 – 1947), operated by the Anglican Church of Canada, moved to Prince Albert in 1947 after it was destroyed by fire.

Survivor Stories

When James Roberts became the first Aboriginal administrator of the Prince Albert residence in 1973, he remarked that when he had attended the school as a boy, he had not liked the fact that he and his fellow students “were not allowed to speak their own native language.”8 These examples make it clear that in schools across Canada, children were told that it violated school policy to speak their own language. (Vol. 5, p. 104)

________________________________________

________________________________________

Sam Ross recalled putting up a fight when the Indian agent came to his family’s home in northern Manitoba to take him to residential school in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan.

Sam Ross recalled putting up a fight when the Indian agent came to his family’s home in northern Manitoba to take him to residential school in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan.

I remember hiding under the bed there; they pulled us out from under the bed, me and my younger brother. We ran, you know, we cried a lot and but that didn’t help better; they took us out. They took us out to the truck; all four of us. My other two brothers walked to the truck. But me and my late, younger brother, we fought all the way, right up, right to the station, train station, CNR station.61

As in Sam Ross’s case, the truck ride was sometimes followed by a train ride. (Survivors Speak, p. 25)

View http://wherearethechildren.ca/en/stories/#story_25 Where are the Children interview with Samuel Ross

________________________________________

When Betsy Olson went home after three years at the Prince Albert school, she had difficulty adjusting to reserve life. And, the food we had the first day was a rabbit, a rabbit, and I couldn’t eat it. I told my sister, “I can’t eat this. is is Peter Rabbit. I can’t eat Peter Rabbit,” I told her, ’cause Peter Rabbit was our favourite story in our books there, and I couldn’t eat Peter Rabbit. All the wildlife we had for about a month, Mom had to buy white man’s food to feed me ’cause I couldn’t eat our, our way of eating back home. I couldn’t eat soup. I couldn’t eat fish. I couldn’t eat bannock. Couldn’t eat nothing. I had to, so Mom had to get extra money to try and buy extra food just for me.378 (Survivors Speak, p. 107)

Betsy Olson described class work at the Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, school as a torment, in which her “spelling was always 30, 40, it was way down. And when we did spelling, sometimes I freeze, I couldn’t move, I just scribbled because I couldn’t move my hand. I can’t remember to spell b, or e, or c. My mind was a blank. I could not bring any letters out. I just freeze.”421 (Survivors Speak, p. 121)

________________________________________

Even when it was not fatal, running away was frightening. Isaac Daniels ran away from the Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, school with two older boys. Their escape route involved crossing a railway bridge. Partway across, Daniels became too frightened to continue and turned back.

And it was already late, it must have been about 11:00, 12:00 o’clock. So, I said to myself, well, I’ll go back, I’ll go back, follow this track all the way, I’ll go back to residential school. So, so that, that was already the sun was coming up by the time I got back to the residential school. And I was just a young fella, you know. So, anyway, I couldn’t get in. Dormitory locked, doors were locked, so I went around the corner, and I slept on the, by my window there. I just have a window, and I used to sneak in and out from the, through the window there. So, I must have sat down there, and I must have fell asleep.471 (Survivors Speak, p. 136)

Isaac Daniels said an older boy robbed him of money that was intended for his sick brother. “He said, ‘You got any money?’ I said, ‘No.’ ‘Let me see it,’ he said. ‘No,’ I said, ‘I don’t have no money.’ Well, he beat the heck out of me, threw me down right in the washroom there, took my wallet, took all my money.”639 (Survivors Speak, p. 171)

________________________________________

Earl Clarke recalled how at the Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, school, many of the boys would start fooling around when the lights went out in the dormitory. Eventually, he said, the supervisor would come out and line up the boys he suspected to have been making noise. He would then “take them down to the end of the hall, and would get out a, a leather strap, just like a conveyor belt type of material. And the kids would come hopping out, crying, bawling, you know, little, little ones ’cause the little ones would get forced to go first.”508 (Survivors Speak, p. 144)

________________________________________

Linda Head was initially excited about the prospect of a plane trip that would take her to the Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, school.

“My dad kissed me, and up I went, I didn’t care [laughs] ’cause this was something new for me.” The plane landed on the Saskatchewan River. “There was a, a car waiting for us, or the truck. But I got into the car, and the boys were in the truck, like an army, an army truck. They stood outside the, outside, you know, at the back, not inside.” The students were driven to the school, which was located in a former military barracks. And we all, there was a crowd when we got there, a crowd of, you know, other students, and we went to the registration table. They gave us, told us which dorm to go, and, and there was a person standing, but the kids were, you know, lining up, and this person took me to the line. And when the line was full, I guess when we were, they took us to the dorm…. We had our numbers, and a bed number. And she told us to settle down. Well, I wasn’t understanding this ’cause it was English, but I followed, you know, watch, watch everybody, and … she took my hand, and guided me to the bed, and the number showed me what number I was, number four, and we had to find number four. So that’s how it was then.

My stuff, I had to set it down, then I, I was under, under the bed, not the higher up, I had the lower bed. So, I was just lying around there … the music was loud, the radio. Everybody was talking in Cree, some of them in Cree, some of them in English, well a little bit of English. And my cousins … we were in together some of them, some of us at the same age, so they came over and talked to me. I said, “Well, here we are.” Here I was missing home already.”78 (Survivors Speak, p. 34)

________________________________________

Wendy Lafond said that at the school, “if we wet our beds, we were made to stand in the corner in our pissy clothes, not allowed to change.”188 (Survivors Speak, p. 60)

________________________________________

________________________________________

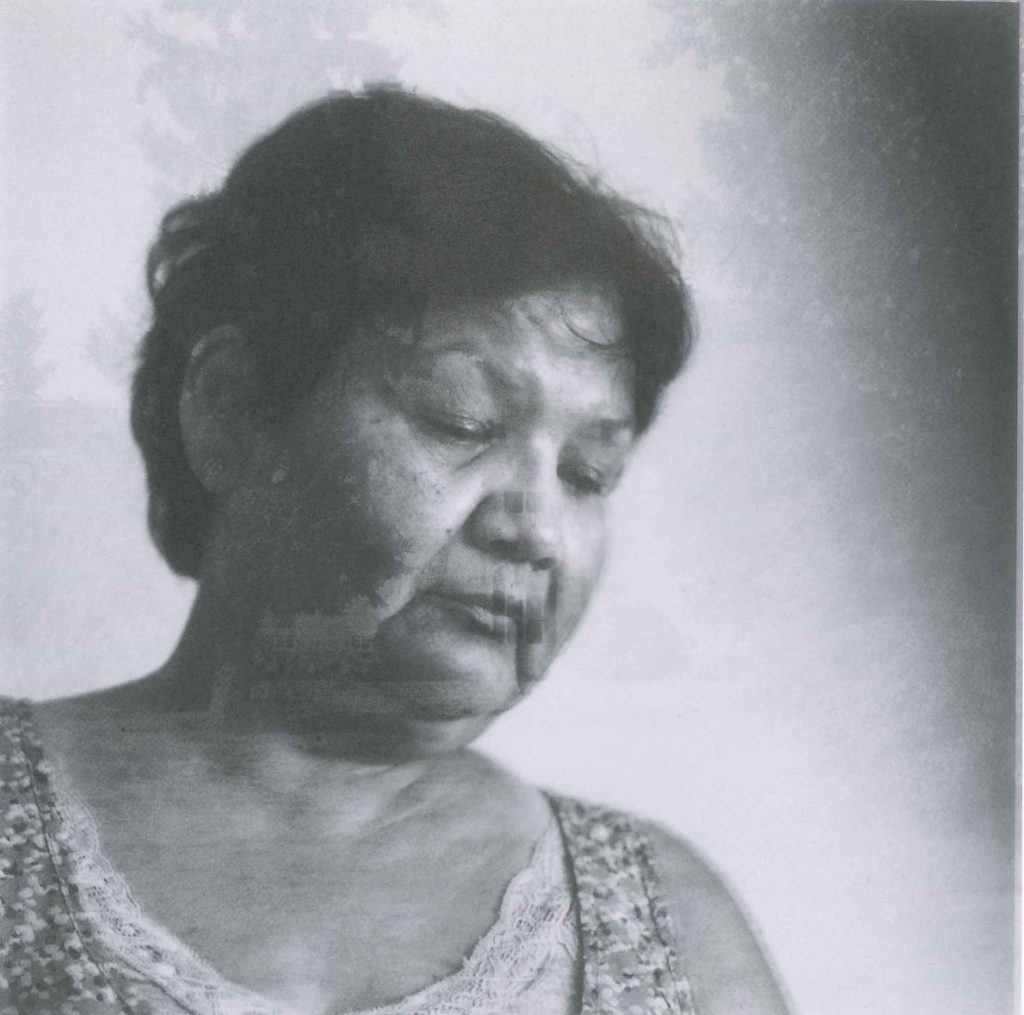

Bernice Logan, 76

Involvement

Teacher and supervisor. All Saints residential school, Prince Albert, Sask., 1949-52 and Shingwauk Home, Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., 1952-55

Currently

Advocate for former teachers of residential schools, Tangier, N.S.

The Anglican Church was advertising for young people to come and give a few years of their life to help these Indian children to work in the Indian residential schools. It was appealing to me to go and work with Indian children.

… We loved it. We enjoyed working with the children. They were well-behaved kids to work with. They were very artistic.

There were different reasons why the children were there. Nobody went out and tore the children from their parents.

… When I heard all this negative reporting, I thought, there’s no way I can let that go unchallenged. I know there were some staff accused of sexual assault, I know that’s happened. That does not mean all the staff out there were dysfunctional and abused the children. They’re calling it a trauma, the darkest chapter in Canadian history. … This is not true.

… We were always proud of everything that we did.

[But now]we’re the criminals.

Jamie Komarnicki The Globe and Mail

___________________________________________

Elder Daniel Nippi

While attending the residential school in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, Daniel was abused sexually by two nuns, a priest, and an older youth. He also suffered physical beatings. On leaving school he displayed many of the symptoms of RSS outlined by Brasfield (2001). He spent the majority of his time from age 16 to 40 in prison for alcohol-related offences, assault, and sexual assault. The only emotion he remembers feeling during this period was anger. He had recurrent dreams and flashbacks about his residential experiences. Daniel reports that he received cognitive behavioural therapy but that this was only partially effective. He eventually turned to Native (Saulteaux) spirituality, and he credits this with saving his life. Pimatisiwin 4(1), 2006

______________________________________________

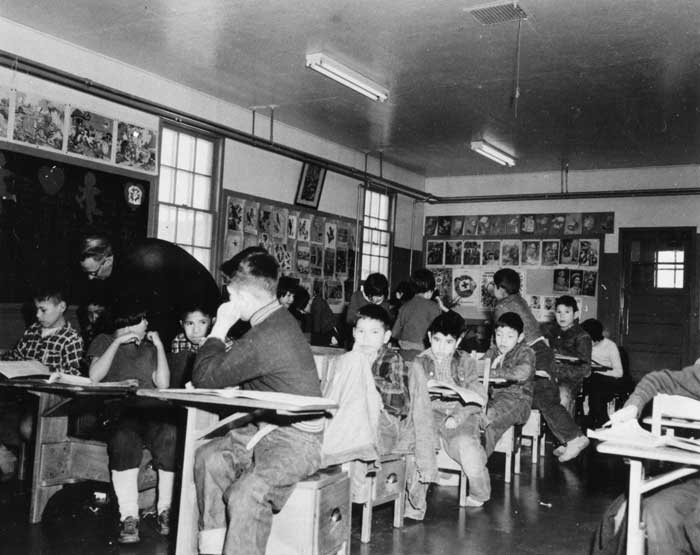

Boarding School Life

By Shirley Bear

This was not a happy school. I was shocked by all the fighting and bullying went on. I learned to keep my mouth shut when I knew who did things they were not supposed to do. But it didn’t help. Usually the whole dormitory was punished until they found out who was guilty. Some of the staff were pretty mean too and did things that were not right – such as pulling ears, slapping heads, and hitting knuckles.

I remember being hungry most of the time as the meals were not very good. We had supper so early and we would be really hungry by breakfast time.

We were made to go to church twice a day and three times on Sundays, but I never really learned anything.

The one thing I will never forget was when I told the principal that I could not speak Cree.

It happened like this. My older brother, Albert, had run away from school and had gone back to the reserve. I got called to the office. There, the principal told me that I was heard saying in Cree that I was going to run away too if my brother didn’t come back.

I told him, “I’m sorry Mr.Mayo but I couldn’t say that in Cree because I don’t talk Cree”.

He said “Don’t be stupid, all Indians speak Cree”.

Then he jumped up, grabbed his strap and hit me all over the back, arms and legs, and head. It was the worst strapping of my whole life. I didn’t understand it. I saw other students strapped for speaking Cree, now I was being strapped for NOT speaking it.

He thought I was lying but what I said was true. I was brought up in a home where my mom spoke only English, my dad spoke both English and Cree so they spoke only English to us kids.

Thank goodness, Mr.Mayo was only a substitute principal and we only had to put up with him for a few months.

The next principal, Rev. A.J. Serase, was an angel. After he came, the whole system changed. He was just like a father to all the students. He was the minister who married my husband and me. He has passed on now, but he will always be a special person to me.

H was part of the good times. I made so many good friends and I am always glad to see my old schoolmates whenever I meet them. I learned a lot about sharing and having compassion for others – I think the good times outnumber the bad times. Or maybe I am just getting too old to remember.

Song by Joseph Naytowhow who was taken to Indian residential school at a young age

Traditional Knowledge Keeper Joe Naytowhow Shares His Story About The RCMP Barracks from Wikiupedia on Vimeo.

____________________________________

St. Michael’s Indian Residential School (1963-1965)

Prince Albert Indian Residential School (1965-1974) “I fought like hell all the time. The nuns would try to drag us away and they’d try to touch me. But I fought back, so they’d throw me in the cellar as punishment. But I loved it down there. It was quiet and dark and no one could bother me. … This nun used to take a broomstick and shove it down there. She did it to all of us. How can you sing to God and treat us like that?”

_______________________________________

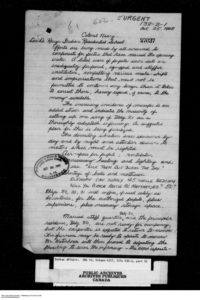

- Increasing incidence of mumps is added strain and indicates the necessity of setting up one wing of Bldg. 21 as a thoroughly adaptable infirmary

- air-space per pupil; ventilation

- unnecessary heating and lighting and use “LOCK THEM OUT DURING THE DAY”

- The ‘scale of issue” to pupils of toilets, basins, etc. in the infirmary has to be reduced, but the movement of sick pupils to washrooms can be distributed over longer periods than possible in dormitories

- The drill hall and its lean-to’s have been my biggest disappointment. If you will refer to my diagram submitted long before work commenced you will appreciate my surprise on seeing:

*young mountain of coal on the main floor of the gym…along with stacked lumber and a conglomeration of useful and useless …materials effectively shuts off use by the children and makes it necessary to provided covered play space elsewhere – but not in the dormitories

*carload of coal was dropped in the door of the “coal” lean-to

*a garage with an imposing wide door where the laundry was indicated

*the laundry sited and outlets cut in the concrete so far over that the toilets intended for the girls were obliterated…

*workshop occupies the space where the bake-oven might have been

*principal has an office-cum-bedroom in one of the rooms intended for sewing and repairing…

- more kitchen equipment is necessary to remove the Rube Goldberg cartoon features

- the local school superintendent (Mr. Piercy) told me that the children were being badly fed. I was able to assure him that unheralded inspection of meals at all times has satisfied me that the children get plenty of good food

- Formerly, like the dining room [wing 33] were “heated” (maybe not) by two small stoves with long hot chimneys of tin pipe–an unsuitable installation where horesplay is inevitable. (The supervisors will have to be alert to prevent the children from swinging from the pipes of the hot-water heating system in the dormitories. Another damaging activity is the picking of wire from bed-springs to make catapults. Many other schools where children kill time in dormitories are similarly afflicted. Vigorous physical activities must be supplied and the dormitories used only at such times and temperatures that will induce no dawdling in getting into bed or getting up.)

- damage-proof play space adequately warmed when only necessary is…a priority

- no music-making machines

- something might be done with those museum piece pianos at the Mohawk institute where also there are some surplus beds and furniture

- …because anything, animate or inanimate, which shows any weakness gets picked at and done to death in short order by these people and the habit of destroying is progressively strengthened. I have had to impound their baseballs from which, for the lack of a few stitches in time, the covers had fallen off and the string was unravelling. When compelled to, they retrieved the covers from their vast playing field….Some of this sort of thing could be prevented or overcome by a more adequate staff in numbers and quality–and the Principal is likely to make some suggestions. For the present I am concentrating on those inadequacies of plant and equipment

“A day-school installation of comparable size scattered over a few northern reserves would have involved an initial outlay of $100,000 with no guarantee that it would exert anything like equal conditioning influence on as many children.”