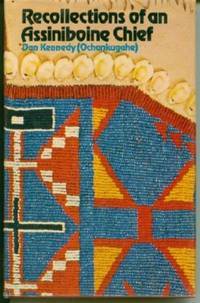

Ochankuga’he – (Daniel Kennedy)

Ochankuga’he – (Daniel Kennedy) was born in the 1870s in Cypress Hills and was of the Assiniboine Nation, which lived on the prairies where Swift Current, Moose Jaw and Regina are now located. They were relocated to the Carry-the Kettle Reserve, where they were “greeted with the littered remains of skulls and skeletons, a grim reminder of a smallpox epidemic which killed two large tribes of Cree Indians in the 1840s.”[1] Kennedy went to Lebret Residential School (St. Paul’s/Qu’Appelle) from 1886 to 1891. His wife Olympe Milton also attended Lebret.

In his memoirs, Kennedy recounted, “In 1886, at the age of twelve years, I was lassoed, roped and taken to the Government School at Lebret. Six months after I enrolled, I discovered to my chagrin that I had lost my name and an English name had been tagged on me in exchange.”18 Until he went to school, his name had been Ochankuga’he, meaning “pathmaker.” The name honoured a trek his grandfather had led through a Prairie blizzard. The new name, Daniel Kennedy, referred to the Old Testament’s Daniel of the lion’s den. The school interpreter later told Kennedy, “When you were brought here, for purposes of enrolment, you were asked to give your name and when you did, the Principal remarked that there were no letters in the alphabet to spell this little heathen’s name and no civilized tongue could pronounce it. ‘We are going to civilize him, so we will give him a civilized name,’ and that was how you acquired this brand new whiteman’s name.”21

Kennedy lost more than his name on that first day.

In keeping with the promise to civilize the little pagan, they went to work and cut off my braids, which, incidentally, according to the Assiniboine traditional custom, was a token of mourning—the closer the relative, the closer the cut. After my haircut, I wondered in silence if my mother had died, as they had cut my hair close to the scalp. I looked in the mirror to see what I looked like. A Hallowe’en pumpkin stared back at me and that did it. If this was civilization, I didn’t want any part of it. I ran away from school, but I was captured and brought back. I made two more attempts, but with no better luck. Realizing that there was no escape, I resigned myself to the task of learning the three Rs.

For Kennedy, even the architecture of the school was foreign and forbidding. He asked readers to “visualize for yourselves the difficulties encountered by an Indian boy who had never seen the inside of a house; who had lived in buffalo skin teepees in winter and summer; who grew up with a bow and arrow.” Kennedy was a successful student who came to enjoy positive relations with Qu’Appelle principal Joseph Hugonnard. In Kennedy’s opinion, Hugonnard’s “genial and engaging personality won for him a host of friends in all ranks of our Canadian nation. His tact and diplomacy commanded the respect and admiration of all who came in contact with him.” He also credited Hugonnard and High River principal Albert Lacombe with making it possible for him and a number of other students to pursue their education after leaving residential school. Kennedy, for example, attended St. Boniface College.25 He did not, however, become a priest. By 1899, he was back in the Northwest, serving as an assistant to an Indian Affairs farming instructor.26 By 1901, he was an interpreter and general assistant for the Assiniboine Indian agency.27 Two years later, he received an engineering certificate.28 In 1906, Kennedy sought assistance from Wolseley, Saskatchewan, lawyer Levi Thompson to petition Ottawa to allow members of the Assiniboine agency to have a holiday for a sports day and promenade. At the same time, he promised they would not participate in Sun Dances. Local Indian Affairs officials and the principal of the Qu’Appelle school feared that the proposed promenade would turn into a dance. Despite their concerns, Indian Affairs granted the application.[2]

_____________________________________________________________

[1] see http://www.sicc.sk.ca/archive/saskindian/a73mar13.htm

[2] TRC. (2015). Canada’s Residential Schools: The History, Part 1, Origins to 1939. The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Volume 1, Part 1, pp. 173-174