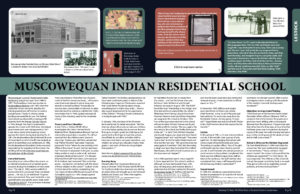

Muscowequan Indian Residential School

Muscowequan Indian Residential School

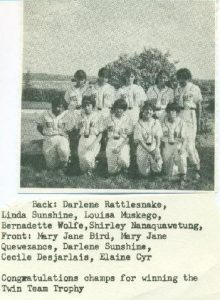

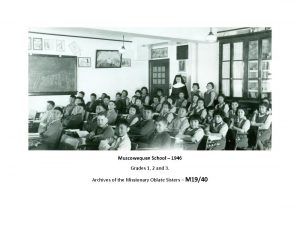

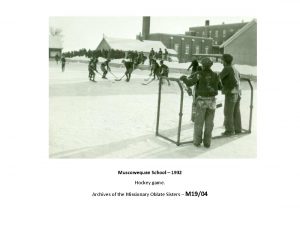

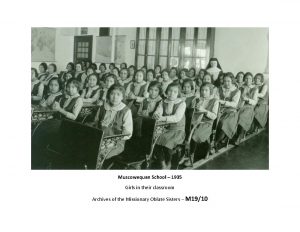

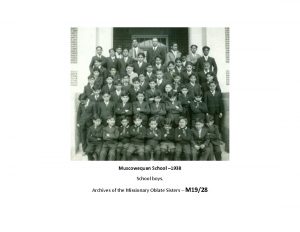

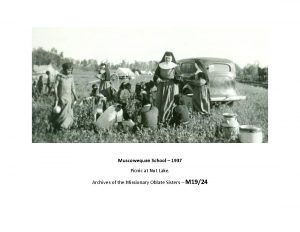

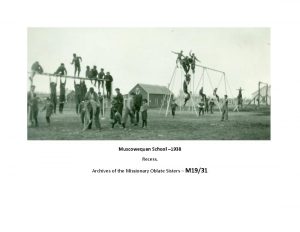

Muscowequan (Lestock, Touchwood) Indian Residential School was open from 1889 to 1997. The boarding school was located on Muskowekwan Reserve until 1895 when the residential school was built, aided by the federal government, off-reserve in Lestock, Saskatchewan (Treaty 4), where a stone building was available for use. The Federal Government purchased Muscowequan IRS property from the Roman Catholic Church in 1924, though the church continued to operate the school until 1969 when the federal government took over management. In 1931 a new three-storey brick boarding school opened, the former being destroyed by fire. In 1981, the Muskowekwan Band claimed 28 acres of Crown land on which the IRS was located, as part of its unfulfilled land entitlement. In 1982, the Muskowekwan Education Centre assumed responsibility for operation of the school. The building still stands (The front cover features the back door of the school).

Survivor Stories

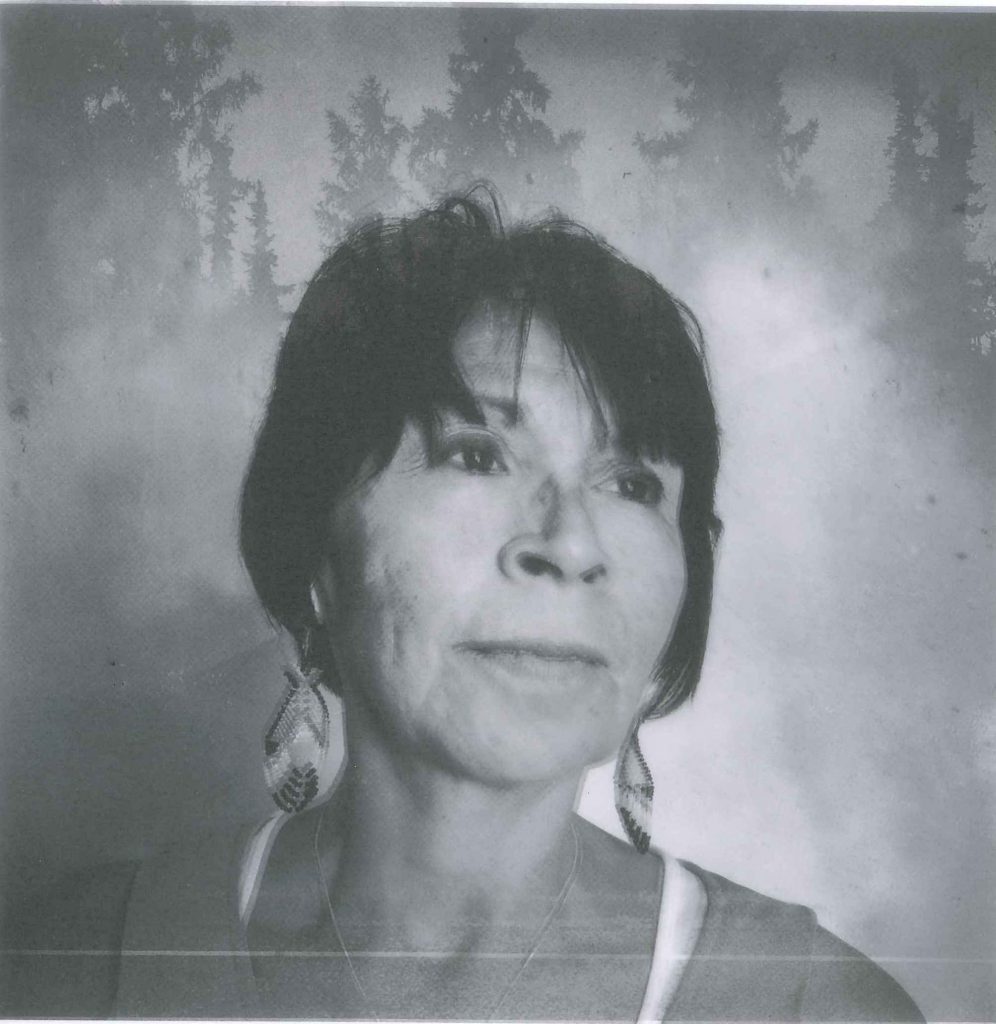

Geraldine Shingoose recalled being punished for not speaking English at the Lestock, Saskatchewan, school. “I just remember, recalling the very first memories was just the beatings we’d get and the lickings, and just for speaking our language, and just for doing things that were against the rules.”140 (Survivors Speak, p. 50)

Geraldine Shingoose recalled being punished for not speaking English at the Lestock, Saskatchewan, school. “I just remember, recalling the very first memories was just the beatings we’d get and the lickings, and just for speaking our language, and just for doing things that were against the rules.”140 (Survivors Speak, p. 50)

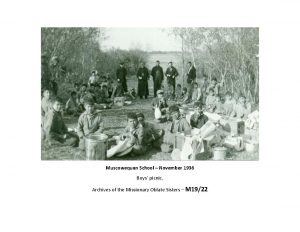

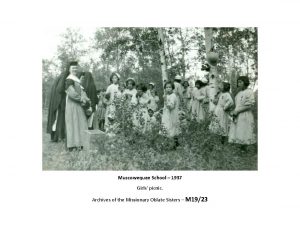

Holidays provided some families with an opportunity to reconnect. However, Geraldine Shingoose’s home in northern Saskatchewan was too distant from the Lestock school for her to return at Christmas and Easter. She stayed in the school for ten months out of the year. We didn’t go home for Christmas, spring break, like all the other kids did, ’cause we lived so far. We lived up north in Saskatchewan. And, and then when I’d see my parents, it was such a, a beautiful feeling, just going back home to them for those two months. And, and then when September would come, I would, I would dread it.353 (Survivors Speak, p. 101)

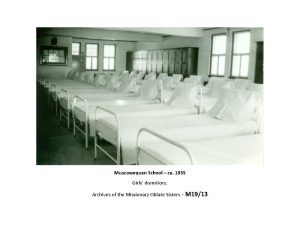

During her early years at the Lestock school, Geraldine Shingoose and other young girls were attacked by older girls. “When I got into the senior dormitory, we, we got those girls, we got them back, and they stopped, they stopped doing that to us, and we got all the, some older girls too, to go after them, and they stopped doing that to us.”618 (Survivors Speak, pp. 167-168)

Geraldine Shingoose had positive memories of the Lestock school principal. “But one of the things I wanted to share about Father Desjarlais was that I really, I really liked him. He was, he treated us good. He was, he was the principal of the school and that, and I know that he, he meant it in his heart to take care of, of the kids, just the staff that were working there didn’t.”684 (Survivors Speak, p. 186)

Geraldine Shingoose took refuge in extracurricular activities. “One of the good things that I would do to try and get out of just the abuse was try to, I would join track-meet, try and be, and I was quite athletic in boarding school. And I also joined the band, and I played a trombone. And, and that was something that took me away from the school, and just to, it was a relief.”697 (Survivors Speak, p. 189)

________________

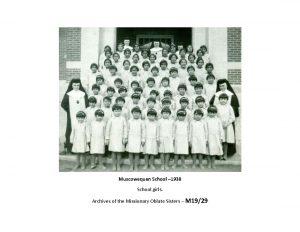

Marlene Kayseas never forgot the number she was given at the Lestock, Saskatchewan, school. “I remember when I first went, my number was 86. I was a little small girl and I was in a small girls’ dorm. And you had to remember your number because if they called you, they wouldn’t call you by your name, they’d call you by your number.”217 (Survivors Speak, p. 66)

The day she left for the Lestock, Saskatchewan, school, Marlene Kayseas’s parents drove her into the town of Wadena.

There was a big truck there. It had a back door and that truck was full of kids and there was no windows on that truck, it was dark in there. And that’s where we were put. There was a bunch of kids there from up north, Yellowquill, Kenaston, and my reserve. And all you hear was yelling and kids were fighting in there and some were crying. And we were falling down on the floor because there was no place to sit, we were standing up. And it seemed like such a long time to get there.57 (Survivors Speak, p. 24)

________________

Hazel Bitternose, who attended schools in Lestock and Qu’Appelle, Saskatchewan, said she enjoyed working in the priests’ dining room. “They had some good food there and I used to sneak some food and able to feed myself good there. So that’s why I liked to work there.”266 (Survivors Speak, p. 77)

_________________

When she was at the Lestock, Saskatchewan, school, Clara Munroe joined a group of girls who were running away. One evening they said, “Come with us,” and I said, “Okay.” I thought, okay, I’ll go with them. Here I didn’t know they were planning to run away. There was twelve of us. So that’s what I did, I followed them. Next thing I knew there was a wagon, team of horses, picked us up like a bunch of cattle, throw us in the wagon, brought us back. Didn’t say nothing, they just, and we used to line up, we used to get in line and we were on our way to the dormitories, bedtime, who do they call? They called me. They called on another girl there. The two of us and I was blamed for that and I didn’t even know a thing about it, so they wouldn’t listen to me. So what did they do? They took us to the principal’s office. The principal was there, there was three nuns there, and not a word, they just pulled my pants down [pause] and the priest, the father principal, gave me a strap. And yet it was I know I was so ashamed I start laughing and that nun said, “She’s laughing,” and he strapped, strapped me harder and longer. I was so embarrassed.523 (Survivors Speak, p. 148)

__________________

Mixed Enrolment

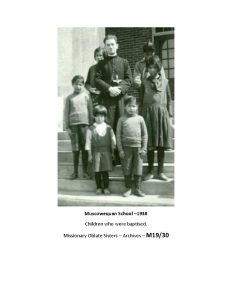

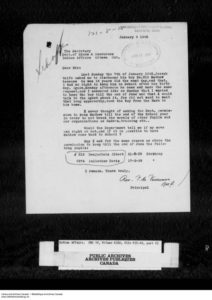

School officials enrolled non-status and mixed-ancestry students. In 1912, for instance, the principal reported, “Under the present arrangement, there is ample accommodation for 25 boys and 33 girls, with a staff of 10. So we took in 11 half-breed children and 1 Indian child under 7 years of age, besides the number on the roll.” (The Métis Experience, p. 24)

Fire

The laundry and garage were destroyed by fire in 1931. The school engineer was injured in the fire and the government declined to pay his medical bills, saying this was the church’s responsibility.(The History, Part 1: Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, p. 468)

In 1993, a fire in the girls dormitory was set deliberately. The slaughter house was destroyed by fire in 1948. In 1977, one inspector found the residence so “drastically overcrowded” that in the case of a fire there “would no doubt [be] a panic situation which could lead to the loss of life.”(Missing Children and Unmarked Burials, Vol. 4, p. 83)

______________

________________

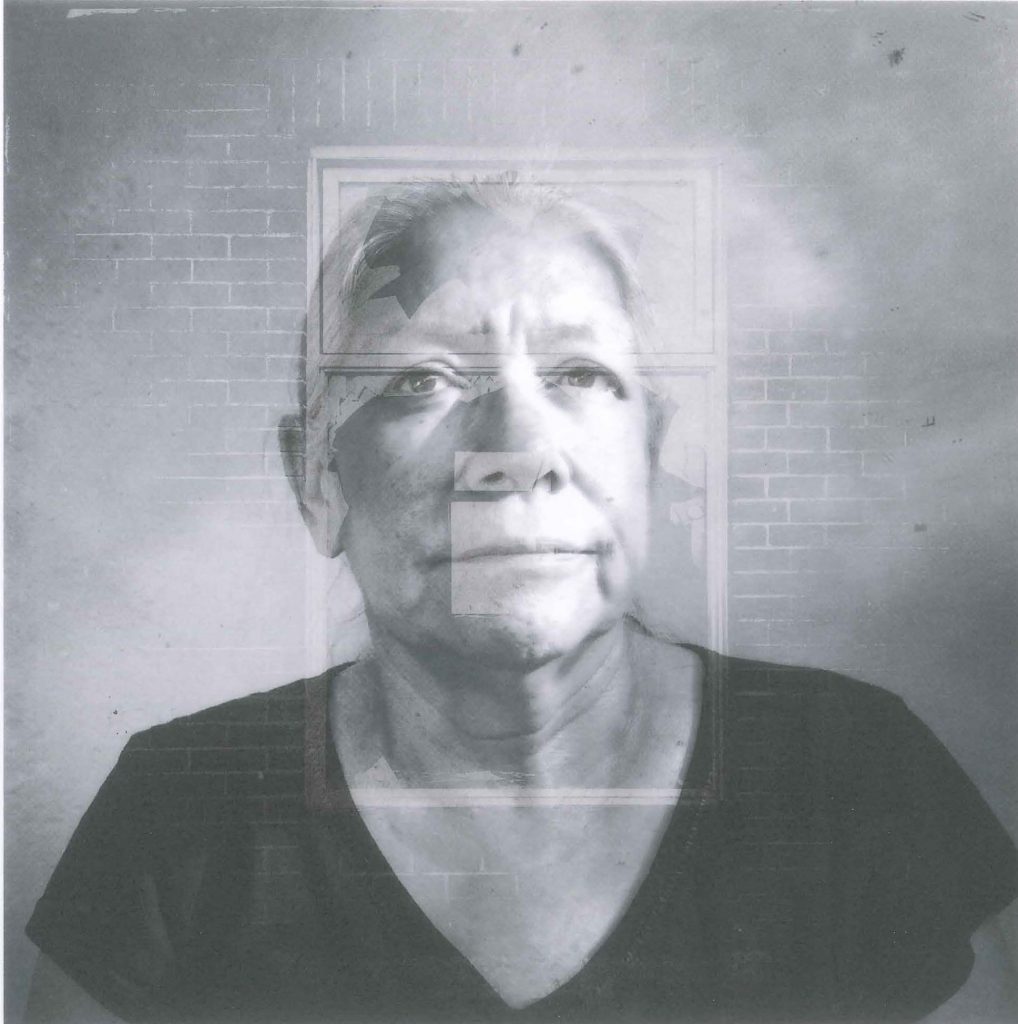

Margaret Roper

Leona Liberty Muskowekwan Indian Residential School1960-1966

________________

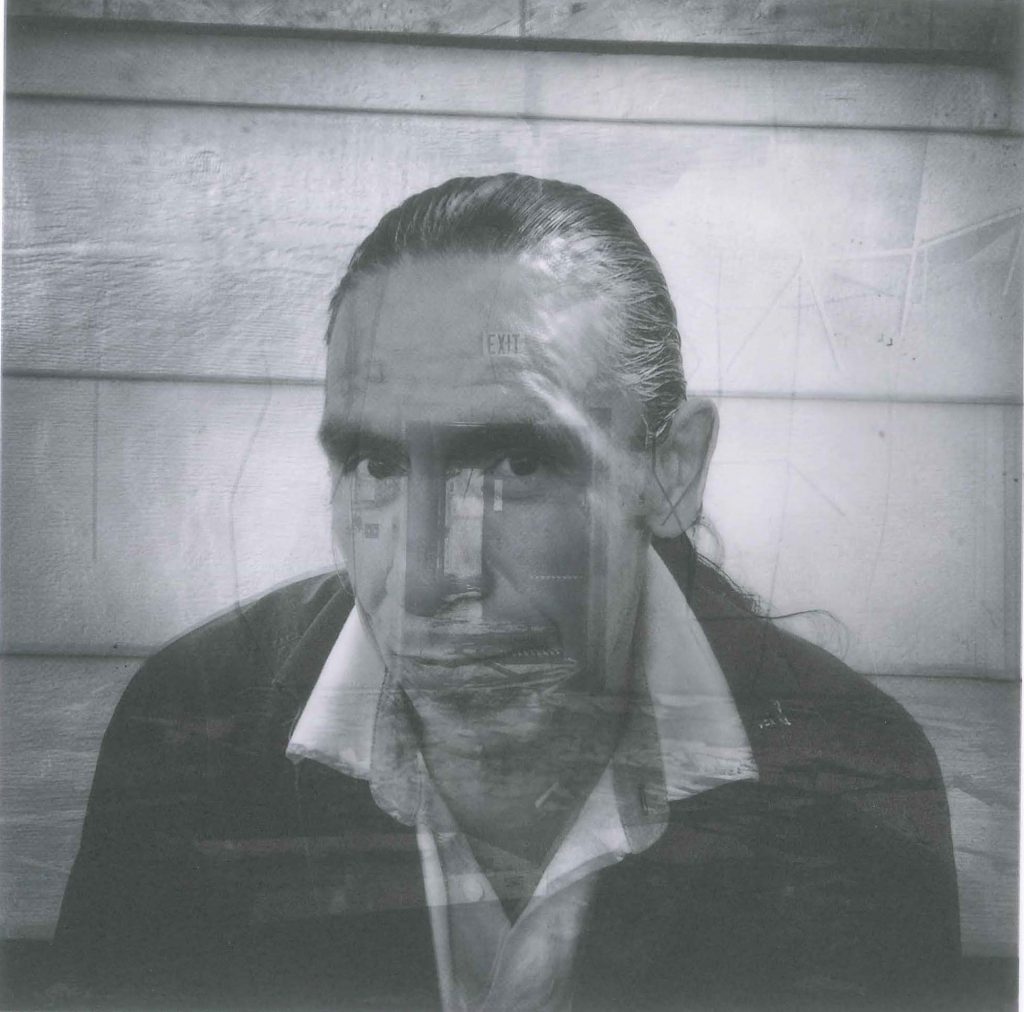

Jimmy Kevin Sayer

Muskowekwan Indian Residential School 1983-1984

“I’ve spent half my life incarcerated, and I blame residential school for that. But I also know I have to give up my hate because I’m responsible for myself. I have three adult daughters and I was in jail for the duration of their childhoods. I have a 2 year old son now and I need to be there for him. I have to be different.” Signs of Your Identity, Daniella Zalcman

________________

Glen Ewenin

Gordon Indian Residential School (1970-1973)

Muskowekwan Indian Residential School (1973-1975)

“Residential school affects how you see the world. I can’t fit into the public anymore, I don’t feel like a normal person. … I don’t even notice myself teaching my kids to be afraid of authority. But it’s made me such a negative person. It changes everything.

—————–

Myrtle Lafontaine

I went there till I was twelve or thirteen

somewhere around there. And then like it was kind of hard for

us being at that school because, you know, like one of the

teachers at least didn’t, you know, treat us very well because

we were Metis ancestry, you know.

_______________________

Metis Stories from Lestock, Saskatchewan (Green Lake)

Researchers searching for child graves near abandoned Saskatchewan residential school

First Nation teams with researchers to find graves of missing children from former residential school