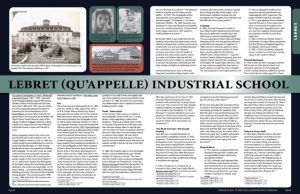

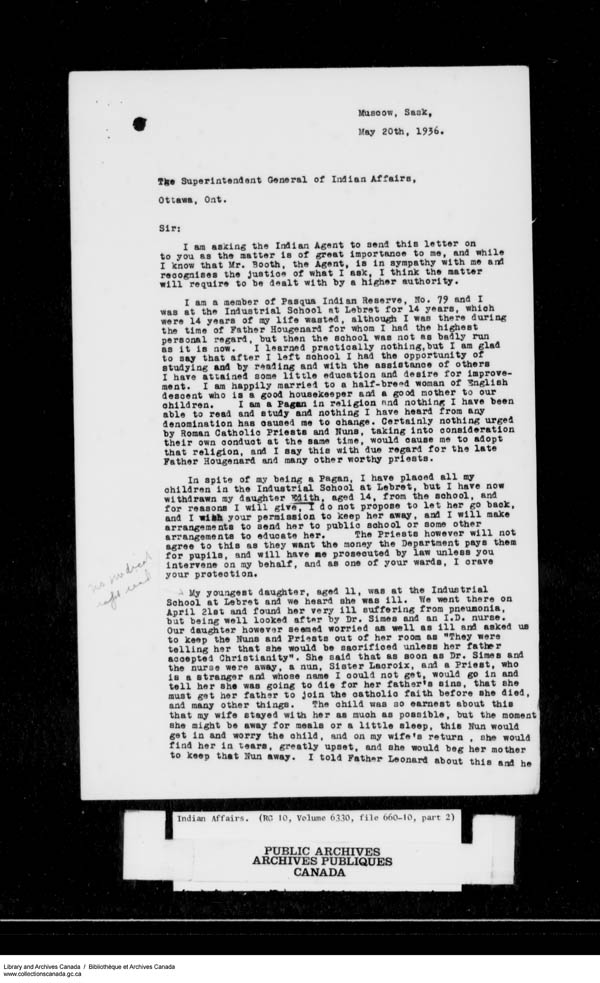

The Lebret (Qu’Appelle, St. Paul’s, Whitecalf) Industrial School, (1884 – 1998) , operated by the Roman Catholic Church (Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate and the Grey Nuns) from 1884 until 1973, was one of the first three industrial schools that opened following the recommendations of the Davin Report, and was fully funded by the government (Battleford was the other in what is now Saskatchewan). This school was located on the White Calf (Wa-Pii Moos-Toosis) Reserve, west of the village of Lebret on Treaty 4 land. Lebret school has a long history as one of the first industrial schools to open and the last to close. Read more by clicking image above.

The Lebret (Qu’Appelle, St. Paul’s, Whitecalf) Industrial School, (1884 – 1998) , operated by the Roman Catholic Church (Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate and the Grey Nuns) from 1884 until 1973, was one of the first three industrial schools that opened following the recommendations of the Davin Report, and was fully funded by the government (Battleford was the other in what is now Saskatchewan). This school was located on the White Calf (Wa-Pii Moos-Toosis) Reserve, west of the village of Lebret on Treaty 4 land. Lebret school has a long history as one of the first industrial schools to open and the last to close. Read more by clicking image above.

1932 Fire at Lebret/Qu’Appelle

A March 1932 inspection of the Qu’Appelle school noted that in two of the school furnace rooms, the pipe “leading from the furnace is almost burned through in places and should be renewed.” The inspector wrote that a fire could start easily in the paper-thin pipes used to conduct throughout the building.40 Later that year, a fire did start, originating in the wiring, rather than in the pipes. It destroyed the school.41 After the 1932 fire, the boys were moved to a nearby Oblate institution and the girls moved into the town hall of the village of Fort Qu’Appelle. Eleven months later, 125 girls were still in the town hall.

Inspector J. D. Sutherland described the town hall as “over-crowded, unsanitary, and a fire-trap. The girls are sleeping in bunks, 5 tiers deep, in the main building, while in the annex, sleeping in the loft, were 54 girls.” The main hall was used as a dining room, recreation room, and dormitory. There were no bathing facilities and the sanitary arrangements were “of the most primitive type.” According to Sutherland, “the odor in the building, mostly of creolin, used for disinfecting purposes, was nauseating.” In case of fire, he doubted anyone would escape alive. There was also danger of the outbreak of epidemics. In all his experience, he wrote, “I have never seen a situation such as is provided for the girls.” (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, p.473)

Parental Resistance at Qu’Appelle School

The parents were at first suspicious of all that the school stood for. They did not wish their children to be brought up as white people, nor to accept their religion, lest they be separated from them in the world to come. The white mans medicine , they said, was bad for the Indians. They objected to the use of see-saws and swings, fearing that their children would break their necks. They were displeased at seeing them move in files, and charged that they were being made into soldiers. “Blowing into tubes”, by which they meant musical instruments, was also regarded with suspicion. (History of the Qu’Appelle Indian School by Sister G. Marcoux,1955, p. 11) Read more…

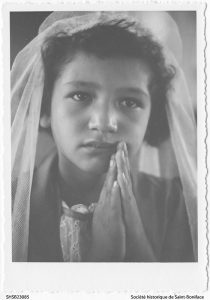

Girls at Lebret

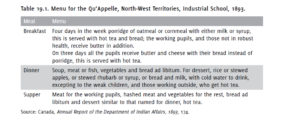

Menu at Lebret

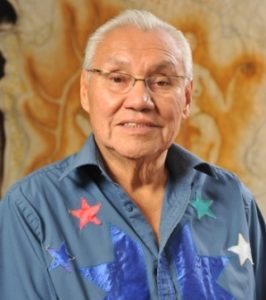

Former Student Stories

Joseph Martin Larocque said, “They scared us. From the time I was small ’til the time the, the priest, the nuns, the whole thing, they scared everybody with dead people, and, you know, talking about the devil. And, and they had this little chart, catechism, where here’s you’re going up this road, and the, the roads are winding like this, and the, the devil’s with a pitchfork. I was scared for a long time. (Survivors Speak p. 87)

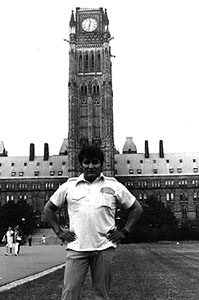

Kerry Benjoe

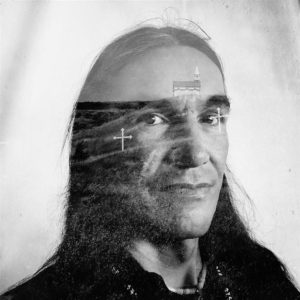

Daya Madhur: Early in my artist residency at the University of Regina, I was invited to support the preservice education students on their professional development field trip to Fort Qu’Appelle where the history and beauty of the valley inspired my creative journey. As I reflected upon the landscape I often sought to personify the hills and question what they have seen and heard. When creating this performance piece I wanted to portray the complexity of the residential school experience in Lebret and Fort Qu’Appelle. Throughout the creation process I visualized layers as seen from my perspective, historic documents, the students’ lived experiences and Elder Starblanket’s narrative, soundscape recordings of the river valley, movement, and even the narrative told through the fabric in the dance. My heart lies in the interdisciplinary and I wanted to include all aspects of the fine arts in this project. The initial performance consisted of a dance/drama piece which interacted with the narratives and projected images. This version is a curated adaptation of the performance piece performed on April 14th, 2016 at the “Walking Together”: Day of Education for Truth and Reconciliation hosted by the University of Regina Faculty of Education and the National Research Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR)

Westwind Evening’s “Whisper in the Wind”

“Westwind Evening, … attended a residential school—the Catholic-run Lebret Indian Residential School, in the Qu’Appelle Valley. Her testimony, though, was not about her own experience in the school, but rather about the brutalizing effects that residential schools have had on her family over generations.

A creative writer, Evening shared her truth in the form of a short story, “Whispers in the Wind,” that details the experiences of a girl growing up in a family haunted by addictions and dysfunction stemming from her mother’s time in a residential school. Read more…

Archdiocese of Regina: A History (Lebret)

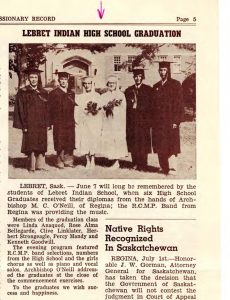

Qu’Appelle Indian School marks 100 years