Andrew Gordon’s daughter Edith claimed the nuns and priests were pestering her about her father being a pagan while she was ill with pneumonia. Andrew Gordon, believing it was their pestering that caused her death, requests the withdrawal of his other daughter.

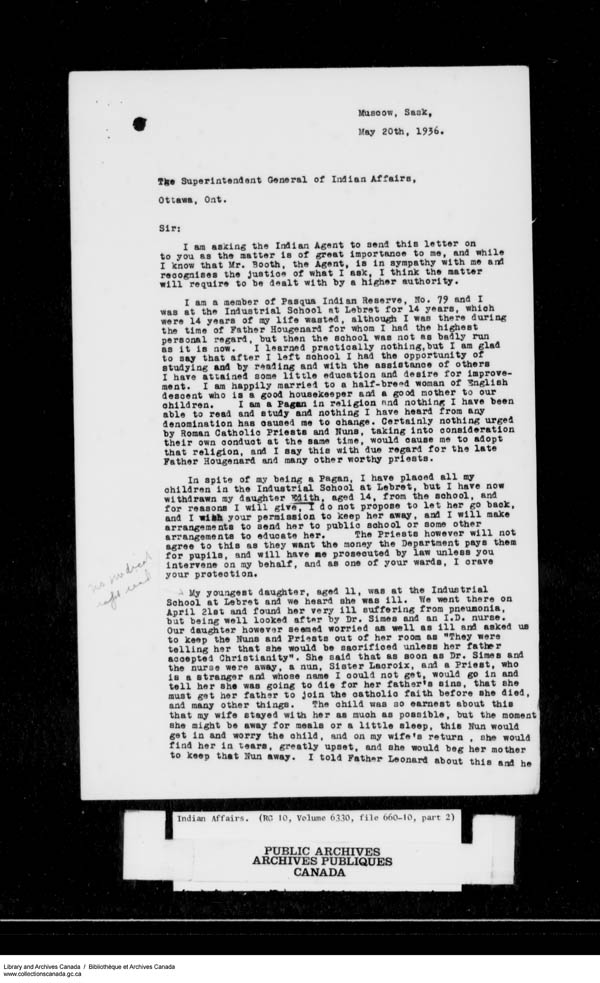

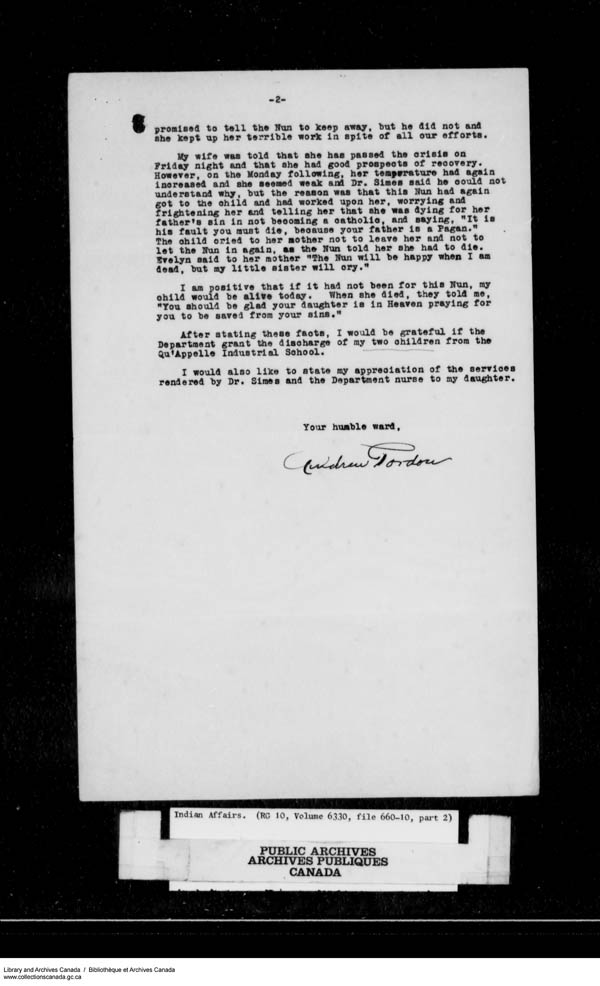

In 1936, Andrew Gordon, a member of the Pasqua First Nation in Saskatchewan, tried to withdraw his older daughter, Edith, from the Qu’Appelle school. In making the request, he noted that he had attended the school as a youth for fourteen years, adding they “were 14 years of my life wasted.” He stated that he was a pagan in religion, but had sent both his daughters to the school. However, his 11-year-old daughter had died from pneumonia at the school. He thought she was given proper treatment by the Fort Qu’Appelle doctor and the Indian Affairs nurse. His daughter had asked him “to keep the nuns and priests out of her room. She said they were telling her that she was going to die for her father’s sins, that she must get her father to join the Catholic faith before she died, and many other things. The child was so earnest about this that my wife stayed with her as much as possible, but the moment she might be away for meals or a little sleep this Nun would get in and worry the child, and on my wife’s return, she would find her in tears, greatly upset…” Despite his requests to the school principal, Gordon said, a nun continued to visit and worry his daughter, who, after rallying briefly, died. Gordon said the school staff told him he should be glad his daughter was in heaven, where she was “praying for you to be saved from your sins.” Given these events, Gordon asked that he be allowed to have his other daughter officially discharged from the school.460 School officials denied Gordon’s allegations, saying the deceased “girl was not bothered in any way at all.”

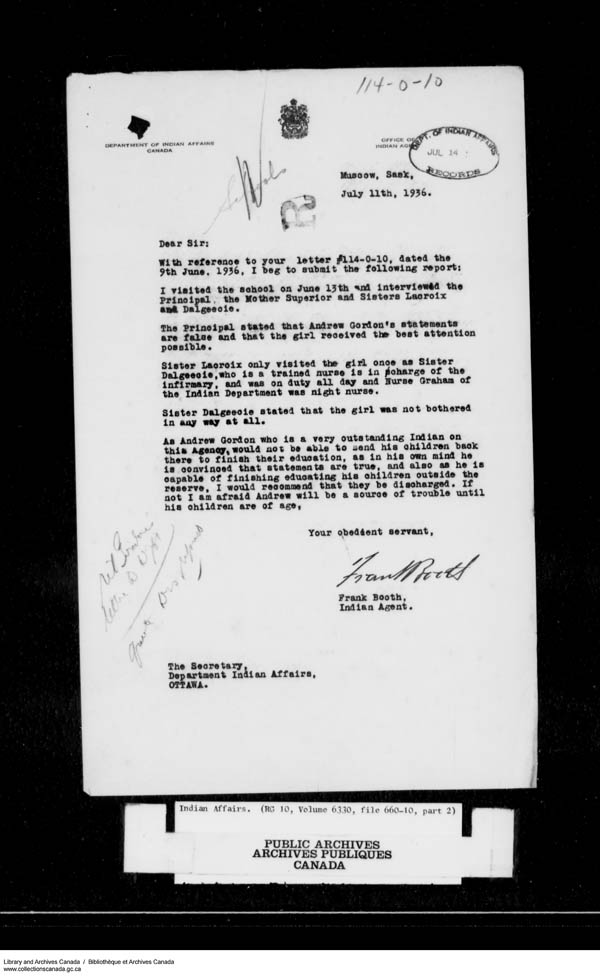

In 1936, Andrew Gordon, a member of the Pasqua First Nation in Saskatchewan, tried to withdraw his older daughter, Edith, from the Qu’Appelle school. In making the request, he noted that he had attended the school as a youth for fourteen years, adding they “were 14 years of my life wasted.” He stated that he was a pagan in religion, but had sent both his daughters to the school. However, his 11-year-old daughter had died from pneumonia at the school. He thought she was given proper treatment by the Fort Qu’Appelle doctor and the Indian Affairs nurse. His daughter had asked him “to keep the nuns and priests out of her room. She said they were telling her that she was going to die for her father’s sins, that she must get her father to join the Catholic faith before she died, and many other things. The child was so earnest about this that my wife stayed with her as much as possible, but the moment she might be away for meals or a little sleep this Nun would get in and worry the child, and on my wife’s return, she would find her in tears, greatly upset…” Despite his requests to the school principal, Gordon said, a nun continued to visit and worry his daughter, who, after rallying briefly, died. Gordon said the school staff told him he should be glad his daughter was in heaven, where she was “praying for you to be saved from your sins.” Given these events, Gordon asked that he be allowed to have his other daughter officially discharged from the school.460 School officials denied Gordon’s allegations, saying the deceased “girl was not bothered in any way at all.”  The Indian agent, Frank Booth, noted that Gordon was an “outstanding Indian,” who was convinced that his statements were true and would be able to see to the education of his daughter if she were discharged. Therefore, he recommended that the daughter be discharged.461

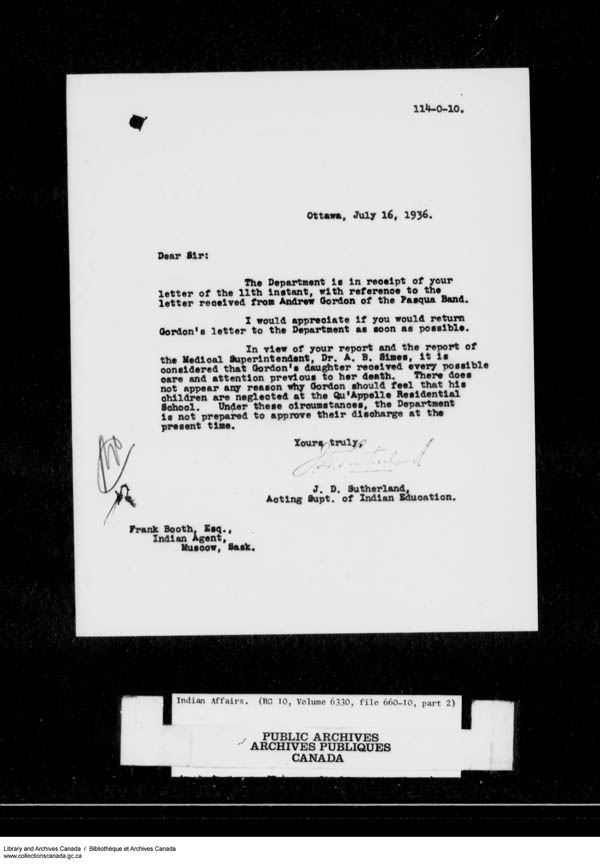

The Indian agent, Frank Booth, noted that Gordon was an “outstanding Indian,” who was convinced that his statements were true and would be able to see to the education of his daughter if she were discharged. Therefore, he recommended that the daughter be discharged.461  Despite this, J. D. Sutherland, the acting superintendent of Indian Education, denied the request, saying that “it is considered that Gordon’s daughter received every possible care and attention previous to her death.”462 As a result, the older daughter, Edith, was not discharged until the fall of 1938, when she turned 16.463 (TRC, 2015, Canada’s Residential Schools: The History, Part 1, Origins to 1939. The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Volume 1, Part 1, p. 445) From Public Archives of Canada Indian Affairs. RG10, Vol 6330, file 660-10, part 2. May 20, 1936, Andrew Gordon to the Superintendent General of Indian Affairs; July 11, 1936 Indian Agent Frank Booth to Department of Indian Affairs; July 15, 1936 J. D. Sutherland to Frank Booth.

Despite this, J. D. Sutherland, the acting superintendent of Indian Education, denied the request, saying that “it is considered that Gordon’s daughter received every possible care and attention previous to her death.”462 As a result, the older daughter, Edith, was not discharged until the fall of 1938, when she turned 16.463 (TRC, 2015, Canada’s Residential Schools: The History, Part 1, Origins to 1939. The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Volume 1, Part 1, p. 445) From Public Archives of Canada Indian Affairs. RG10, Vol 6330, file 660-10, part 2. May 20, 1936, Andrew Gordon to the Superintendent General of Indian Affairs; July 11, 1936 Indian Agent Frank Booth to Department of Indian Affairs; July 15, 1936 J. D. Sutherland to Frank Booth.

Raymond Gordon: “My dad was Andrew Gordon Senior. He went to the day school across the lake from Asham Beach (late 1800s). Then he went to Lebret for 14 years. He could not read or write after spending 14 years at school. He spent most of his time at school either working on the farm or working for the school. After he left school he began to farm using an oxen and a walking plow. He built a house. My dad became a leader and a spokesman for the Pasqua Band. He learned to read and write after he went to a meeting and was asked to read a letter for the people at the meeting. They said, “You spent 14 years in school and you cannot read or write?”. After that he made up his mind to teach himself how to read and write.”

Source: Elders Statements Book II, Pasqua First Nation, 2003

https://www.pasquafn.ca/fileadmin/user_upload/PFN_CommunityPlan_31May2010_sm.pdf