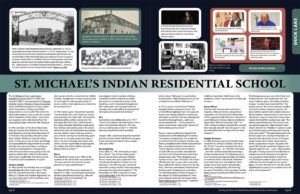

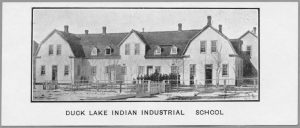

St. Michael’s Indian Residential School | Duck Lake

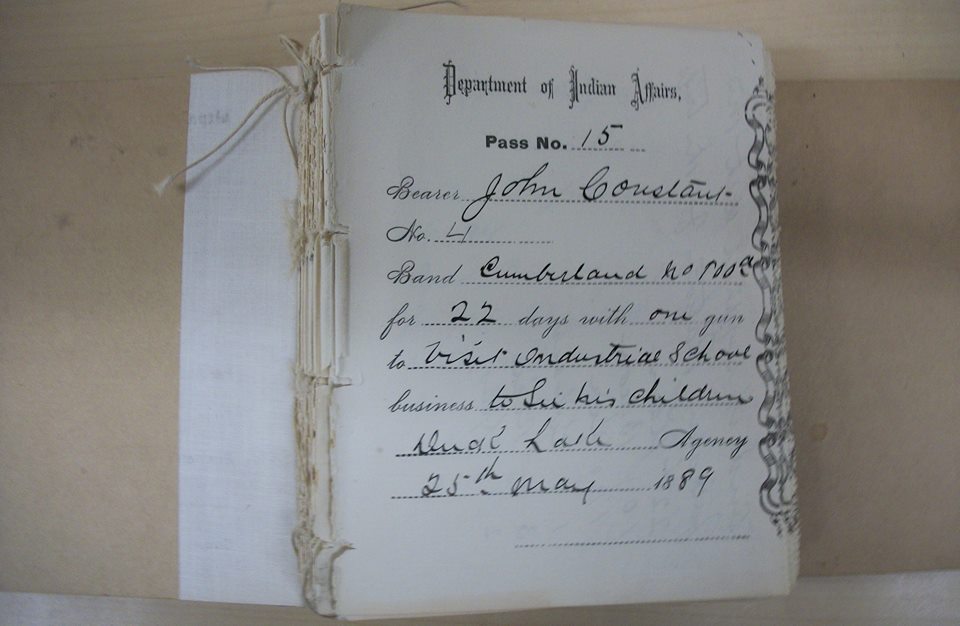

The St. Michael’s (Duck Lake) Indian Residential School opened in 1894 and closed in 1996. It was operated by the Roman Catholic Church (Oblates of Mary Immaculate, Sisters, Faithful Companions of Jesus, Sisters of the Presentation of Mary, and Oblate Indian-Eskimo Council) until 1982 when the Duck Lake residence came under the control of the Saskatoon District Chiefs. The school was located a half a mile (.8 kms) from the Town of Duck Lake, facing the lake (Treaty 6).

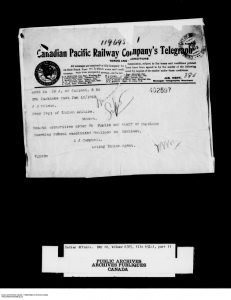

Girls in service experiment

Date: 1910, April. (Indian Affairs, RG10, Vol 6305, file 652-1, part 1)

Rev. O. Charlebois (Principal) requested that school girls (Flora Thomas and Elize Eyahpaize) be placed in the service of white families (Dr. Touchette). The rationale was to give them practical experience in the type of work they would be going into when they left the school. The request was granted and the girls were placed in service for a period of 5 months. The employers were satisfied with their performances and more students were put into service: Josette Kamiokiskaw (Mr. Gervais, a Duck Lake farm family) and Madeleine Ananae (Mr. Lanouvielle, a farm family). Principal Charlebois wrote the Dept. “My only aim is to protect our pupils against the influence of their old parents.” . The principal then asked the Department if the first two girls could be retained in service, kept under the authority of the school, even though they would reach the age of 18 and be discharged. The Dept. agreed with the conditions that the girls remain in service and do not marry. The same was granted for the second set of girls.

“Flora Thomas and Elize Eyahpaize continue to please her employers and they are even much appreciated for their knowledge of general housekeeping as well of their ability in sowing, cutting and fitting all kinds of garments. The trouble now is that their parents claim them and want them home. Because the usual time for their discharge has come and they do not want to leave them any longer under my control and service. What am I to do?…It would be a pity to send them home where they will find nearly nothing to do and where they will spoil themselves. On the other hand it is hard for me to resist alone against their claims. they think that my object in keeping their children at service is my own interest I am seeing and not theirs.” April 12, 1910.

Charlebois asks the Department to ask the Indian Agent, Mr. Macarther, “to be kind enough to make the parents understand that I am forced by you to not let go their children….In case you prefer I should give them their liberty to go home, you have only to let me know. I will do it, although I will be very grieved because I know it will be a draw back for these girls.”

The Dept. replies that “Mr. Agent Macarthur will be written to and asked to so advise the parents.” April 22, 1910

Mr. Macarthur replies May 30, 1910, that at a meeting of Beardy’s and Okemasis reserves held on the 20th, “they requested me to write you protesting against their children being kept, after they are of age, at the Duck Lake boarding school I explained to them the Principal’s good intentions in so keeping the, but they claim that they can take just as good care of their own children as the Principal can, and that it was neither fair nor right to keep them against their own and their parents’ wishes. They all object to children who are in their last year at school, being sent out to work, saying that they are not sent there to work for others, and that if they are through with school they should be allowed to return home.”

The Department replied to Mr. Macarthur that it hoped his “influence with them will overcome their present objection and that the results will speak for themselves.” June 14, 1910.

Agent Macarthur then replies June 29, 1910, “I have explained to the parents of those girls who are working out, as carefully and plainly as I could…but I have totally failed to get the parents in any way to consent or approve of them working out. I have hitherto refrained from expressing my personal opinion on the subject,…but being on the spot, it is probably my duty now to do so. It may be taken as beside the question that Principal Charlebois is acting entirely in what he believes to be the very best interests of the girls and the Principal is an able earnest man. It should not be forgotten that these girls have been at school for 12 years; they know how and can do household work just as good as white girls of their age; they can wash and iron, make or repair clothing. Indeed, in all this, as far as knowledge of the work, they are ahead of the average white girl. Now this being so, what further object can be gained by placing them with strangers to work for a wage against their willing consent? To my mind it is akin to slavery. If twelve years of careful training has failed to make them competent to take up their life’s work, a few months of compelled service will not mend matters….

Sandy Thomas, says he wants his girl at home, she has been away twelve years. He had in the past other two girls at this school, both of whom, wile there, became mothers. He does not want this to happen to the third, and claims that he is just as able to look after her as the Principal is, and that it is altogether wrong to keep the girl away from him. Then Eyahpaise wants his girl home as her mother is a helpless invalid, being bed-ridden for years. While this girl will not be 18 until November, she is working out. That being so, she should be at home taking care of her mother….I have written at this length, not from any desire to interfere with the work, but because of the constant complaints of the parents.”

The Department then writes to Agent Macarthur on July 7, 1910, “In view of the attitude of the Indians and your remarks on the subject, the Principal has been instructed to recall these girls from service and grant the final discharge of those who have reached the age of eighteen years.”

The Department writes to Principal Charlebois informing him of the protests of the parents and that “it is not considered politic to place their girls in service against their wishes, nor to retain them in the school beyond the age of 18 years, … The greatest care must be taken not to antagonize the Indians,as all efforts to recruit will prove futile. For this and the further reason that they are quite within their rights in raising the objections it has been decided to recall to the school those girls who have not reached the age of 18 and grant the final discharge of those who have attained that age.”

The next letter, dated Sept. 29, 1910 is to inform the Department that Principal Charlebois has been elected Bishop and a successor is Rev. Father Gabillon.

1910 high death rate among students and day schools discussed

Indian Agent Macarthur to J.D. McLean (Dept. of Indian Affairs) December 27, 1910, Duck Lake Boarding School in Sask. (RG10, Vol. 6305, file 652-1, part1)

“The death rate in this school is again returning to its high mark, two of the inmates having died during the year and two others dying. For a time after the introduction of the steam heating and the excellent ventilating system provided by the Department the death rate was low, and I was in hopes that it would remain permanently so. Everything that can be done is done to keep the scholar’s of this school in health, but in spite of all, the above result. I have always been of the opinion that the building was not suitable for the purpose as it has altogether too many dark corners and a lack of light. I understand that Tuberculosis Bacilli dies in a very short time if exposed to sunlight, but will live on indefinitely if kept in the dark. It may be thought that the children catch the disease while visiting their parents, but it must be remembered that they only visit for a month of the year and that too in the summer, when they spend their time on the open prairie and sleep in tents. Eleven months of the year is spent at school, and no one responsible can get beyond the sad fact that these children catch the disease while at school. To find how our day schools compared with this report on the Duck Lake Boarding school, I have looked back over the past 10 years with the following result, viz.- In 1900 there were 19 children from the One Arrow’s Reserve at the Duck Lake Boarding school. Of these 10 are living to-day and 9 are dead. Of 22 children on the roll of the LaCorne north school in 1900, 17 are alive to-day and 5 are dead; and of 15 on the roll of the La Corne south school in October 1903, 14 are to-day living and one is dead. While, in the latter case, the pleasing result may not be altogether due to the teacher, no doubt her motherly care materially helped to procure the result. It may be thought that the James Smith’s people are, on the whole, more healthy than the One Arrow’s people, but I find that during the past 10 years the average duration of life on the James Smith’s was 25 years, while on the One Arrow’s reserve it is a fraction over 27 years notwithstanding the heavy toll taken by the Duck Lake Boarding school. … The Department should realize that under the present circumstances about one-half of the children who are sent to the Duck Lake Boarding school die before the age of 19 or very shortly afterwards, and that, because they are kept in a building whose every seam and crevice is doubtless burdened with Tuberculosis Bacilli.”

Macarthur makes mention of the parents of Beardy’s and One Arrow’s requesting day-schools, suggesting the death rate may be the reason…”as so many of their children die at the Boarding school, or come home from the Boarding school to die.”

J.D. McLean (Ottawa) to W. J. Chisholm, Inspector of Indian Agencies in Prince Albert, January 12, 1911.

McLean forwards the letter from Macarthur, stating it is “worthy of serious consideration” and requests “that you give the matter your personal attention. He suggests another cause of the higher death rate as being “a lack of care in examining prospective pupils.”

Inspection report, Jan. 26, 1911

Agent’s statement: “The statement made by the Agent regarding the death rate among pupils and ex-pupils of the school for the past ten years is based on accurate information gathered from the certified quarterly returns of the school.

Unsanitary conditions: “The conditions that might act as a protection for germs and thus tend to the propagation of the disease are as follows:”

Basement made of clay, no light; Floors made of fir or spruce had cracks where germs could be harbored; Walls were plaster with numerous small cracks; Lighting in some areas was sparse or dim; outside closets too close to the school.

Dormitories were large and airy.

Doctor Reid and other physicians were consulted. They “informed me that tubercular disease would be very slightly developed indeed if it were impossible to discover it by a careful examination of the lungs, the glands of the neck and chest, and the bones and muscles of the limbs. They agree with the suggestion that some help might be obtained in connection with the examination of pupils for admission by an inquiry into the health record of their parents and other near relations.”

Calisthenics and breathing exercises were practised regularly under the direction of the sisters who had made a study of these for the purpose.

Indian commissioner Laird to the Dept. of Indian Affairs, February 10, 1911

“Though the Duck Lake Boarding School Buildings appear to be in an unsanitary condition, yet it is doubtful whether this defect is the chief cause of the excessive mortality at school. … In the early days, too, when the school was in process of organization, the church authorities were very eater in canvassing for recruits, and the Indian parents more readily consented to permit their delicate children to go to the Boarding school than the stronger ones, whom they wished to retain for home work.”

“The principal cause of the unsanitary condition of the school is doubtless the want of a sufficient supply of pure water and a proper disposal of the sewage. Outside closes near the schools are a great nuisance and should be abolished as soon as possible.”

J.D. McLean (Ottawa) to Indian Agent Macarthur

“the Department has decided not to open a day school on Beardy’s Reserve, but to allow the Duck Lake Boarding School to serve the educational needs of that locality…The question of opening a day school on One Arrows Reserve has been held in abeyance.”

1912 agreement for the management of the Duck Lake Boarding school (RG10, Vol. 6305, file 652-1, part1)

States that no child shall be admitted to the said school who is under seven years of age

1915 More children less revenue:

February 22, 1915: 104 pupils on the roll. Mr. Chisholm (inspector) reported that “there are several children under the age of seven years who are resident in the school and attending classes, but who are not as yet grant earners.”

“Mr. Chisholm states that the large attendance from some of the reserves, vis.-Beardy’s, Petaquakay’s and One Arrows, is due to the fact that the population of these bands is made up to a considerable extent of ex-pupils of this and other residential schools and the parents who are themselves ex-pupils are so anxious to have their children enrolled that they bring them themselves to the Principal as soon as they are eligible for admission. … I think the Department would be quite justified in allowing them to take in twenty or twenty-five additional pupils. Mr. Chisholm states that the revenue of the school for the current year will be about $4000 below that of the proceeding year through the failure of last year’s crops.”

March 4, 1915 J.D. McLean to C.P. Schmidt (Indian Agent): “the Department has decided to allow them ten more pupils. this will bring the number of grant earners up to 110 and the increase will date from the first of January, 1915.”

Series of Fires

Fire set near gas plant (Sept. 5, 1917)

Fire set in boys recreation room (Sept 16, 1917) and straw stack set on fire on Sept 11, 1917

Measures discussed and student responsible for fires sent to Wolsley Detention Home

Concerns over wartime regulations (1918)

Canada Food Board regulations for flour rations of concern

Principal Rev. H. Delmas to Indian Affairs, May 23, 1918. Canada Registration Board demands all people over the age of 16 have to register. “Our boys can help…but our Indian girls are not fit to go out and work for white people. Experience has proved us that the Indian Girl when discharged from School, must be well taken care of and protected in a special manner until her marriage. But could not our girls, those of the School as well as those discharged and living in the neighborhood, help to win the war? count not the Depar/, send us wool with directions and they would knit socks, mitts, mufflers, ect.?

J.D. McLean to Rev. H. Delmas, June 7, 1918. “…you will shortly receive from the food board a license giving you permission to get sufficient supplies for your school. It will be necessary for all the pupils in your school over sixteen years of age to register at the proper time, but they will not be called upon to go away from the school to work.”

Discussion over the lack of French language teaching at the school (1918)

In July 1918, Principal Rev. H. Delmas questioned why French language was not being taught at Duck Lake Boarding School. J.d. McLean replied, “It is not the policy of the Department to teach French in our Indian Schools except in the Province of Quebec.”

On Aug. 22, 1918, Rayment Denis (Interprovincial Association) replied, “Your reply…fills me with surprise and indignation. French, from a federal point of view, is official just the same as English. The money that maintains these Indian schools comes from various taxes levied on the French-Canadian population just as much as on the English speaking population. Your policy, is, therefore, a flagrant injustice as well as being a violation of the agreement of Confederation. I as you, therefore, in the name of the French-Canadian Association which I represent, to kindly advise me that this policy will be modified. If not, I shall have to appeal direct to the Minister of Interior himself, and further, I shall give over the official documents that I possess to Mr. Rudolph Lemieux, who will bring this matter to the attention of Parliament.

On Aug. 29, 1918 McLean replies, “the Department does not intend to alter its policy with regard to the education of Indian children…So far as I am aware there is nothing in the British North American Act which bears upon this subject.

Sale of land to Government of Canada in order to have a new school built 1925.

In 1921, the Principal, Rev. Delmas informs the Indian Commissioner W. M. Graham that the old school building, which was erected in 1894, is now in a dilapidated state, and requests a new school. Graham forwards the request to the Dept. of Indian Affairs, requesting their consideration of the matter. A.F. MacKenzie responds that buildings and land in connection with the school are the property of the church authorities, and suggests the building be funded by them. In January 1922, Duncan Scott writes Rev. Guy (University of Ottawa) asking for a definite proposal from the church for the sale of the 1500 acres of land at the present site of the boarding school. “The Department will not place a building on property that does not belong to us.” Father Guy recommends the construction of an up-to-date school. Graham visited the school in October 1923 and confirms that “the building is in such a state that I consider it would be a waste of money to make any extensive repairs, the time has arrived when the question of erecting a new school should be seriously considered.” In 1924 a proposal is sent to Duncan Scott by Rev. Delmas asking for $50/acre. The Government is not willing to pay that amount. Duncan Scott offers $30/acre for 717 acres of farm land. He instructed them to not delay on their response because ” any delay might render it impossible for us to erect the school.” Rev. A. Naessens accepts the offer reluctantly because the need for a new building was so urgent. On July 2, 1924 Duncan Scott sends a telegram to accept the offer and instructing the contractor to proceed with work immediately. The church retained the land around the church and cemetery.

Survivor Stories

_________________________________________

“We are strong people because we are still here and we will be here until the end of time,” said MaryAnn Napope, a residential school survivor whose parents, grandparents, siblings and children all attended St. Michael’s School in Duck Lake. Star Phoenix June 2015

___________________________________________

Mary Greyeyes went to St. Michael’s at Duck Lake at the age of Five. She was the first Indigenous woman to join the army. Read more.

Mary Greyeyes went to St. Michael’s at Duck Lake at the age of Five. She was the first Indigenous woman to join the army. Read more.

_____________________________________________

An important video about recognizing intergenerational IRS trauma in students by Deanna Ledoux

__________________________________________________

My name is Ray Sanderson, and I’m from James Smith First Nation. At a very young age I went to residential school like so many of our people, and I suffered in there. I remember the loneliness, being lonesome for home… Read more

‘He was a great man’: Advocate for First Nations veterans dies (Ray Sanderson)

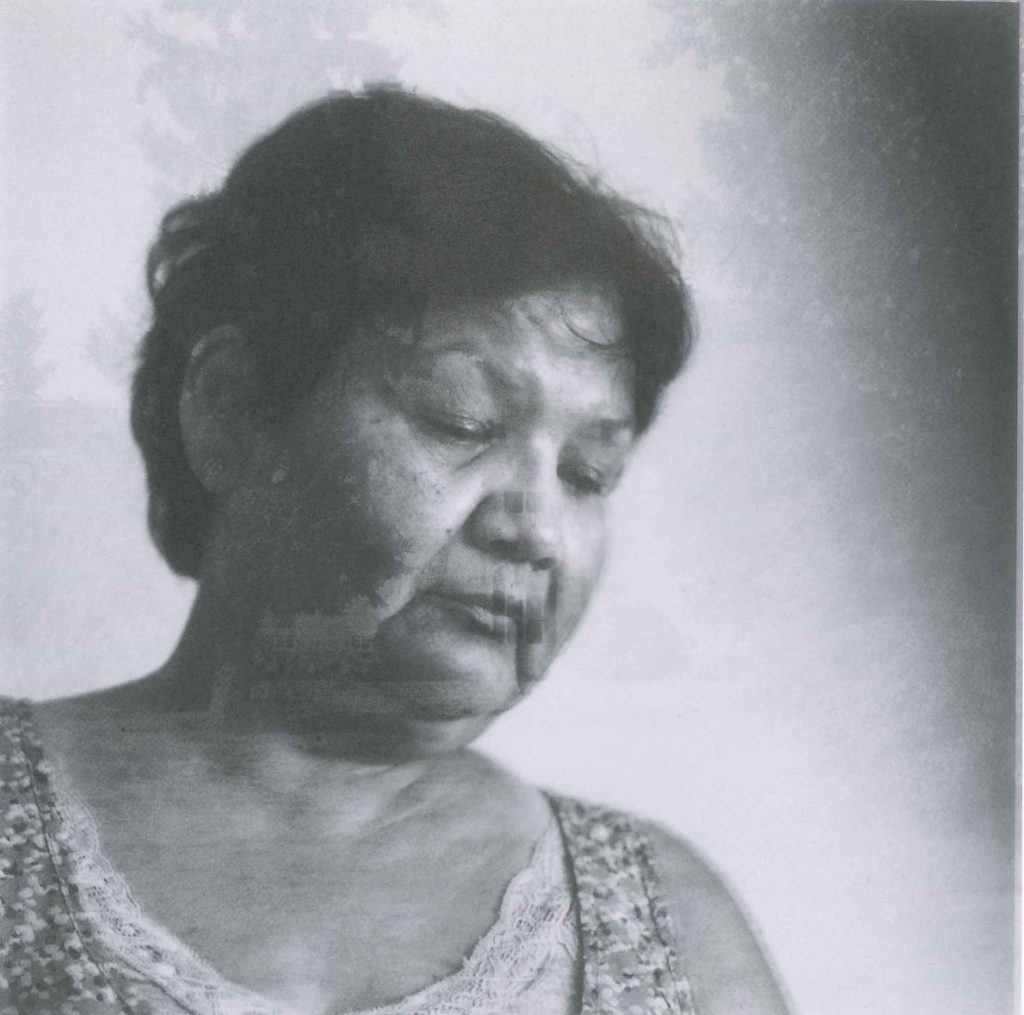

Audrey Eyahpase

St. Michael’s Indian Residential School (1963-1965)

Prince Albert Indian Residential School (1965-1974)

“I fought like hell all the time. The nuns would try to drag us away and they’d try to touch me. But I fought back, so they’d throw me in the cellar as punishment. But I loved it down there. It was quiet and dark and no one could bother me. … This nun used to take a broomstick and shove it down there. She did it to all of us. How can you sing to God and treat us like that?” Daniella Zalcman, Signs of Your Identity

_____________________________________

Dan Keshane interview, 18 Feb. 1992, Keeseekoose Reserve, recalled two priests, successively principals at St. Michael’s school, Duck Lake, who were sexually active with female students or other women (Miller, J.R., 1996, Shingwauk’s Vision: A History of Native Residential Schools, p. 73.).

_____________________________________