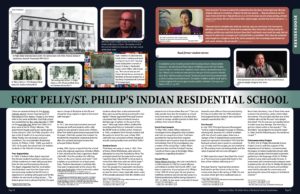

Fort Pelly (St. Philip’s) Indian Residential School near Kamsack

Fort Pelly (St. Philip’s) Indian Residential School near Kamsack

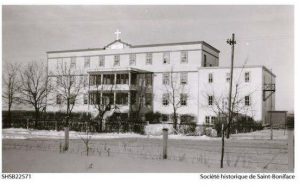

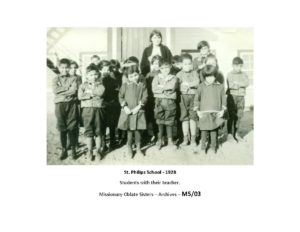

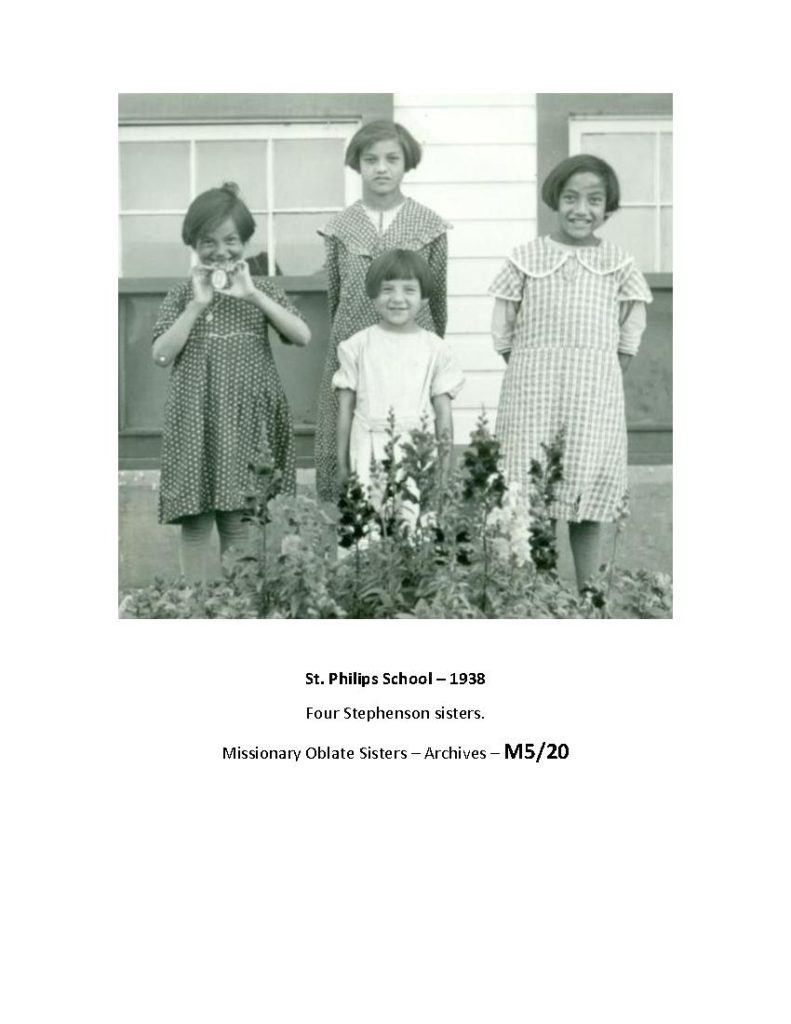

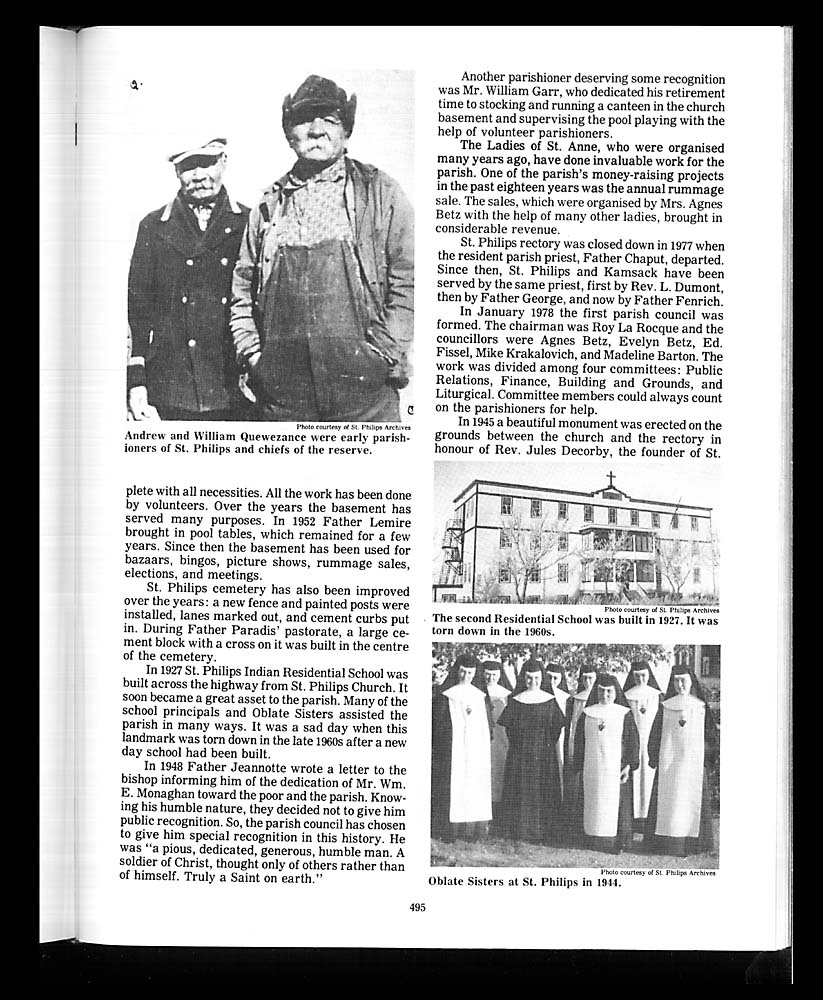

There are separate listings for the Roman Catholic church schools near Kamsack at Keeseekoose First Nation, (Treaty 4), but these refer to the same institution. Fort Pelly school was established by Rev. Jules Decorby in 1895 on the Fort Pelly Trail, about two miles (3.22 kms) west of the St. Philips Mission. The government began paying per capita grants to the school in 1905. Fort Pelly closed in 1913 due to the ill health of its second principal, Father Ruelle, low enrolment, and poor conditions. The second Indian Residential School, St. Philips, (1928 – 1969), was built in 1927. At it’s peak, the school had 132 resident students in the 1964/65 school year.

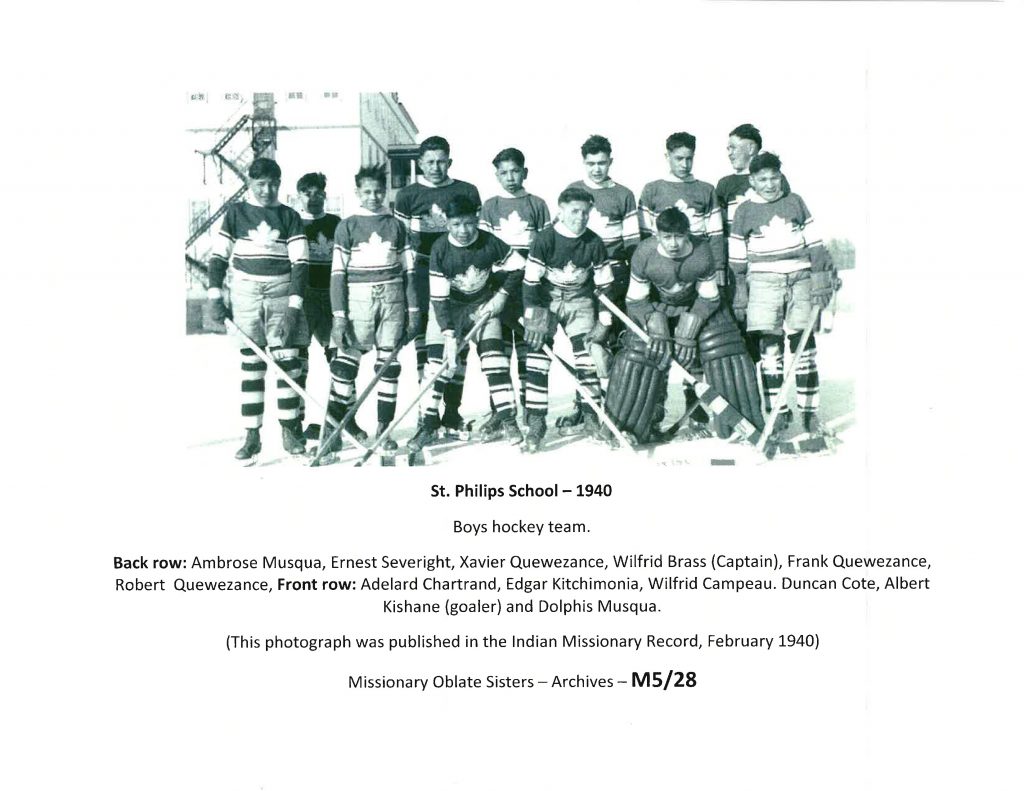

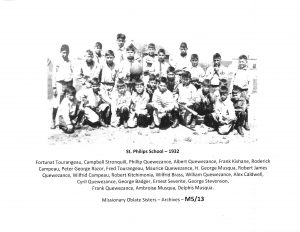

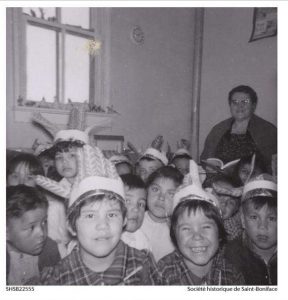

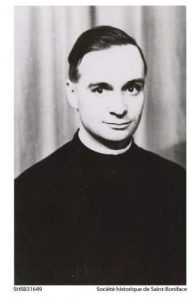

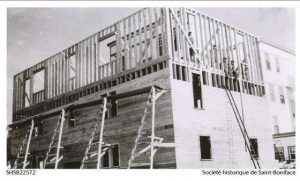

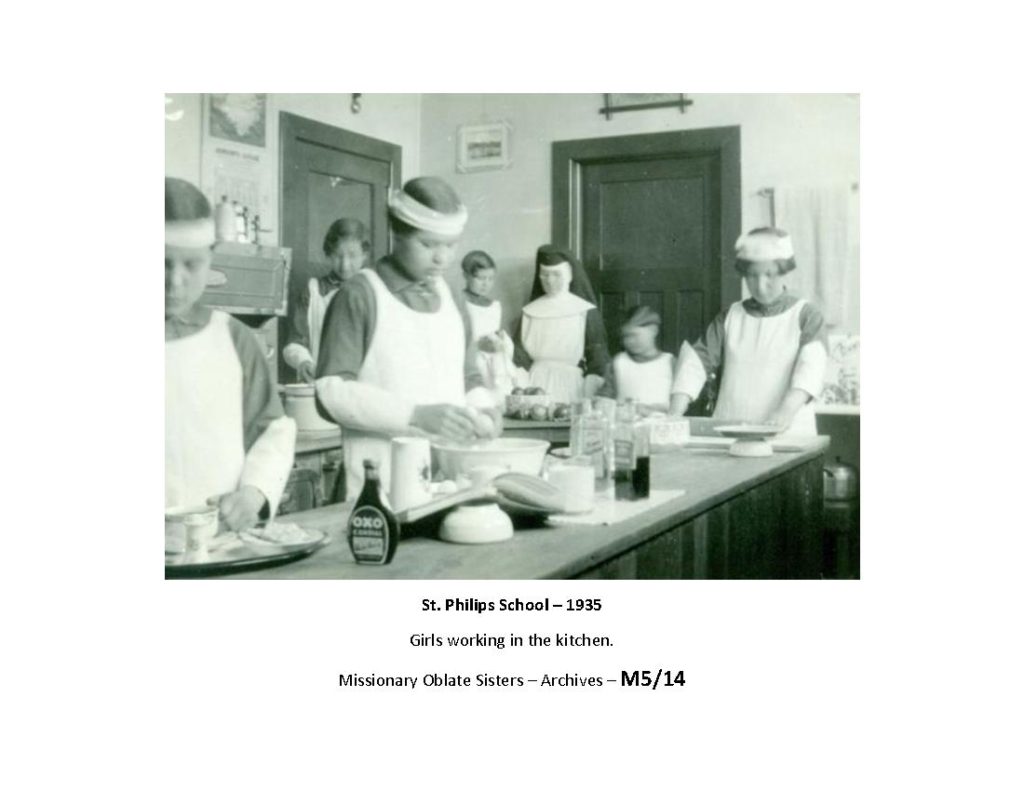

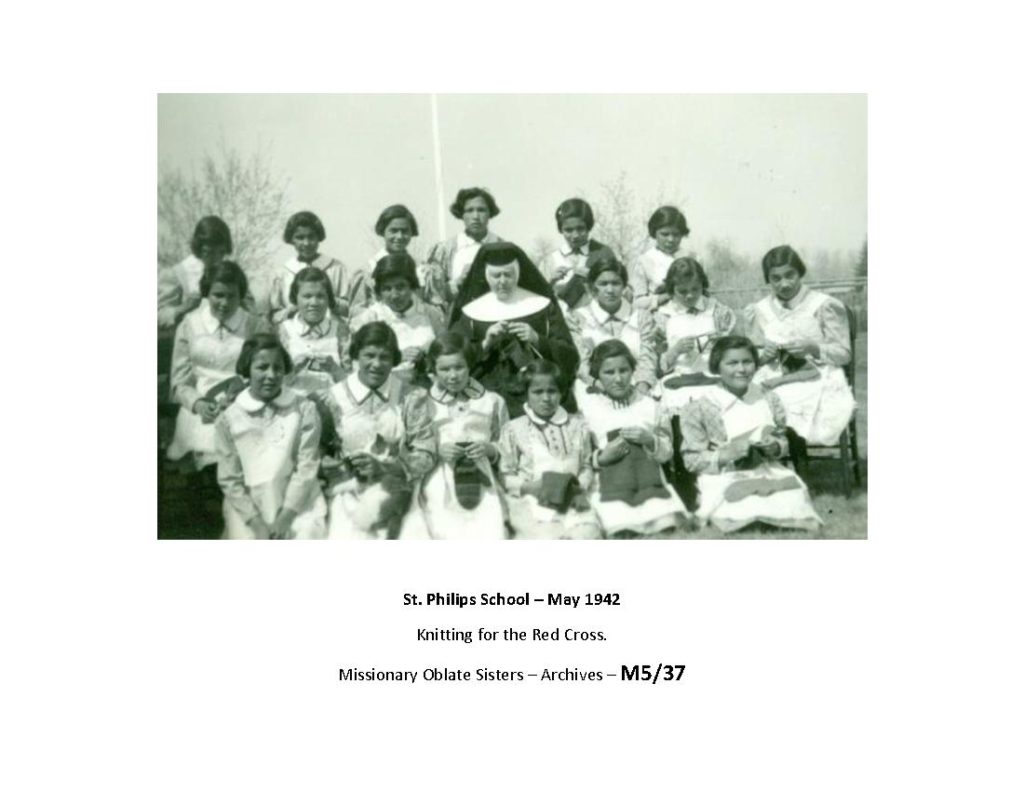

Father Jules Decorby had worked in First Nations communities of the region starting in 1880, founding the Fort Pelly Mission in 1895. In 1902, Father Decorby relocated the mission to the midpoint between Fort Pelly and Kamsack. According to the Historic Society of Saint Boniface, “In 1901, the Oblates presented a request to the Indian commissioner for Manitoba and the Northwest Territories to open a residential school near the Keesekoose Reservation. The first boarding school was built there with logs daubed with mortar. It had two stories and measured 45 by 40 feet. Two years later, grants started to arrive from the Canadian government, which provided the institution with a more adequate budget. Initially, teaching was done by lay people: Miss Ouimet, Miss Bédard, and also Miss Ouimet’s replacement Loulou Atwater. In 1905, 5 Sisters of Saint Andrew (Sisters of the Cross) took over teaching. In 1906, the mission began to be called the St Philip Neri Mission and became the region’s post office. In 1908, the Sisters of the Cross left the mission. In 1909, Archbishop Langevin called on the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, who accepted the responsibility of teaching in Fort Pelley’s school in 1910. They only stayed for three years, leaving the mission in 1913. Between 1913 and 1928, the mission ran a day school with teaching provided by lay people approved by the Oblates (L1051 .M27R 31-33). In 1913, nineteen students were attending. The Oblates believed it would be easy to maintain the school with a minimum of 30 or 35 students. In 1928, the day school was closed in favour of a new residential school. Its construction had begun the year before. On March 9th, the Missionary Oblates returned to St Philip and the school opened its doors to 45 students on the 16th of April. In 1961, the building of a new residential school began, which was inaugurated on May 16th, 1962. According the 1966-1967 report from the Oblates, there was a total of 345 Indigenous students in grades 1 through 8, at the Pelly Indian agency, of which 95 were boarders and 207 were day pupils at St Philip’s, 28 were day pupils at Whitesand, and approximately 20 were day pupils at Key school. June of 1969 saw the closure of St Philip’s Residential School, which was run by the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate. The principals of the school from 1925 to 1969, the period when the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate ran the school, were Conrad Brouillet (1925-1934), Alphonse Paradis (1935-1942), Paul-Émile Tétrault (1942-1947), Adéodat Ruest (1947-1953), Jean Lambert (1953-1955), Raymond Beauregard (1955-1957), Léonard Charron (1957-1963) and Edmond Turenne (1963-1969)”

Survivor Stories:

William Whitehawk interview, 18 Feb. 1992, Kamsack, recalled priests who were sexually active, in two cases with schoolboys, and in one with Indian women on the reserve near St. Philip’s school. At the Community Hearing in Key First Nation, Saskatchewan, in 2012, Survivor Wilfred Whitehawk told us he was glad that he disclosed his abuse. “I don’t regret it because it taught me something. It taught me to talk about truth, about me, to be honest about who I am…. I am very proud of who I am today. It took me a long time, but I’m there. And what I have, my values and belief systems are mine and no one is going to impose theirs on me. And no one today is going to take advantage of me, man or woman, the government or the RCMP, because I have a voice today. I can speak for me and no one can take that away.34 (Honouring the Truth Reconciling for the Future, p. 13)

____________________________________

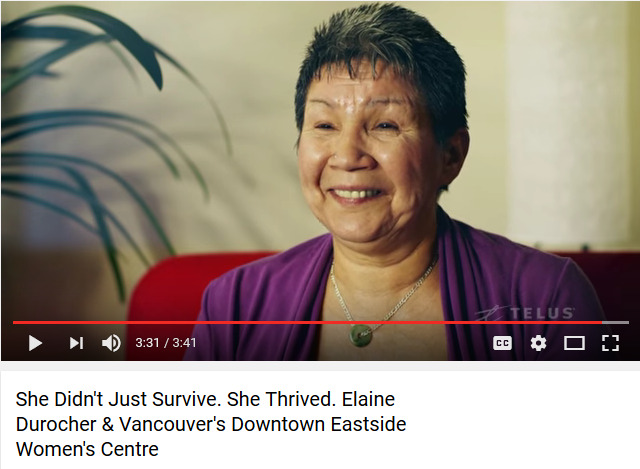

Elaine Durocher found the first day at the Roman Catholic school in Kamsack, Saskatchewan, to be overwhelming. “As soon we entered the residential school, the abuse started right away. We were stripped, taken up to a dormitory, stripped. Our hair was sprayed.… They put oxfords on our feet, ’cause I know my feet hurt. They put dresses on us. And were made, we were always praying, we were always on our knees. We were told we were little, stupid savages, and that they had to educate us.” (Survivors Speak p. 41)

Elaine Durocher found the first day at the Roman Catholic school in Kamsack, Saskatchewan, to be overwhelming. “As soon we entered the residential school, the abuse started right away. We were stripped, taken up to a dormitory, stripped. Our hair was sprayed.… They put oxfords on our feet, ’cause I know my feet hurt. They put dresses on us. And were made, we were always praying, we were always on our knees. We were told we were little, stupid savages, and that they had to educate us.” (Survivors Speak p. 41)

Durocher felt that she received no meaningful education at the school. Rather, she learned the tools for a life on the fringes of society in the sex trade. “They were there to discipline you, teach you, beat you, rape you, molest you, but I never got an education. I knew how to run. I knew how to manipulate. Once I knew that I could get money for touching, and this may sound bad, but once I knew that I could touch a man’s penis for candy, that set the pace for when I was a teenager, and I could pull tricks as a prostitute. That’s what the residential school taught me. It taught me how to lie, how to manipulate, how to exchange sexual favours for cash, meals, whatever, the case may be.” (Survivors Speak, p. 120)

Durocher recalled that the staff at the same school took advantage of the children’s simplest needs to coerce them into sexual activities. “And then after church, there was a little canteen in the church, and the priest would sell us candies. Well, after they got to know us, they started making us touch their penis for candy. So not only were we going to church to pray, and go to catechism, but we were also going to church ’cause they were giving us candy for touching them. We didn’t have money.” (Survivors Speak, p. 158)

_______________________________________

Campbell Papequash had been raised by his grandfather. When his grandfather died in 1946, Papequash “was apprehended by the missionaries and taken to residential school.”

When I was taken to this residential school you know I experienced a foreign way of life that I really didn’t understand. I was taken into this big building that would become the detention of my life and the fear of life. When I was taken to that residential school you know I see these ladies, you know so stoical looking, passionate-less and they wore these robes that I’ve never seen women wear before, they only showed their forehead and their eyes and the bottom of their face and their hands. Now to me that is very fearful because you know there wasn’t any kind of passion and I could see, you know, I could see it in their eyes. When I was taken to this residential school I was taken into the infirmary but before I entered the infirmary, you know, I looked around this big, huge building, and I see all these crosses all over the walls. I look at those crosses and I see a man hanging on that cross and I didn’t recognize who this man was. And this man seemed dead and passionate-less on that cross. I didn’t know who this man was on that cross. And then I was taken to the infirmary and there, you know, I was stripped of my clothes, the clothes that I came to residential school with, you know, my moccasins, and I had nice beautiful long hair and they were neatly braided by mother before I went to residential school, before I was apprehended by the residential school missionaries.

And after I was taken there they took off my clothes and then they deloused me. I didn’t know what was happening but I learned about it later, that they were delousing me; ‘the dirty, no-good-for-nothing savages, lousy.’ And then they cut off my beautiful hair. You know and my hair, my hair represents such a spiritual significance of my life and my spirit. And they did not know, you know, what they were doing to me. You know and I cried and I see them throw my hair into a garbage can, my long, beautiful braids. And then after they deloused me then I was thrown into the shower, you know, to go wash all that kerosene off my body and off my head. And I was shaved, bald-headed.

And then after I had the shower they gave me these clothes that didn’t fit, and they gave me these shoes that didn’t fit and they all had numbers on them. And after the shower then I was taken up to the dormitory. And when I went to, when I was taken up to this dormitory I seen many beds up there, all lined up so neatly and the beds made so neatly. And then they gave me a pillow, they gave me blankets, they gave me sheets to make up my bed. And lo and behold, you know, I did not know how to make that bed because I came from a place of buffalo robes and deer hides and rabbit skins to cover with, no such thing as a pillow.73 (Survivors Speak, pp. 33-34)

Reflecting on the work he did at the Roman Catholic school in Kamsack, Saskatchewan, Campbell Papequash also noted that the students provided much of the labour needed to keep the school in operation. “I think there was a lot of slave labour in there because we had all the children, they all had to do, we all had our own jobs to do. You know all the residential school children maintained that whole building by cleaning it up and looking after the building. You know some guys worked in the boiler room and the furnace room, in the laundry room and with the dryers and the vegetables and working in the root cellar looking after the vegetables. (Survivors Speak, p. 79)

Campbell Papequash had the opportunity to work with mechanized farm equipment. “I came from a family, you know, from a family that knew how to raise, how to look after horses and raise horses, and look after cattle and they put me out there. But there is a few good things that I learned in residential school because when I look back at the farming industry you know they had modern equipment there, modern machinery in the residential school, you know, they had these tractors and they had these combines and they had these swathers.” (Survivors Speak, p. 83)

____________________________________________

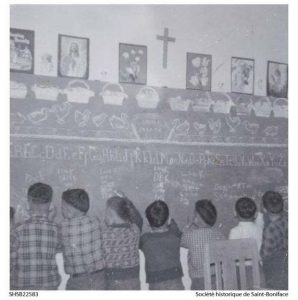

Clara Munroe felt she received a very limited education at the Roman Catholic school at Kamsack, Saskatchewan, with the biggest focus on religion. “It was always prayer, praying, singing hymns in Latin, something we didn’t even understand. That’s how that school was operated.” (Survivors Speak, p. 123)

_____________________________________________

______________________________________

Elwood Friday

St. Phillips Indian Residential School

Attended 1951-1953

“I’ve never told anyone what went on there. It’s shameful. I am ashamed. I’ll never tell anyone, and I’ve done everything to try to forget.” Daniella Zalcman, Signs of Your Identity

_____________

Andrew Quewezance went to St. Philips Indian Residential School in 1958. The following are some quotes from the Prince Albert NCTR hearings.

“I started school in 58. Like I said, the abuse was right in your home at a very young age because my siblings picked that up in residential schools; they brought it home with them. I was treated like a dog…”

“I go back, … the first day of school, my first memory of school, I was the smallest boy out of 60 boys. My first experience was my head being put in a toilet with piss and shit. I’m going to tell people the way it really was, for me.”

“As a young child I never learned anything in the residential school. You can not learn anything in fear, shame.”

“I went to school for a total of 14 years in my time. Some of it was in a residential school. I come out of school after 12, after 14 years with a Grade 3 education. I couldn’t help my children do their homework, Grade 2, Grade 3, because I didn’t know how. I would brush them off, ‘I’m busy, I’m busy, I’m doing something else,’ ashamed that I couldn’t help them in their homework…”

“I’m learning behaviours at 57 years old which I’ve never experienced. My dad never told me he loved me. He died 51 years ago. My mother told me she never loved me. She died 48 years ago; I was 7, 8 years old. Am I going to deny my children of that? No. I’m going to make that effort. Tell them I love them, support them. Those are the things I live with on a day-to-day basis …[a] constant reminder of what happened to Native people like myself in the residential system.”

“My mother was killed in ‘65 while I was in a residential school. My mother passed away, they told me. The priest called me up and told me, your mother passed away. You know how I understood that? I ran down stairs and jumped on a bench and looked out a window. I thought she was passing by. That was my understanding of my mother passing, passing away. They took me home for a day, overnight, the funeral. We buried her, went back into school, just like that, two days of my life, and I was looking for comfort, at night. I would go looking for comfort; I would go talk to other boys, older boys. What did they do? They took advantage of me. They put me in their beds; they sexually abused me as long as they wanted. I would go to school in the morning and I couldn’t sit on the chair. Those are the things I remember about residential school. That’s my education folks; that’s what I was taught.”

“We went to school in a three story building. …People say here today, they were shipped away…for me I could see my house across the fields. Two, three miles away. I would stand there for hours watching. Trying to find out who was milling around outside, who was walking around. Guessing. I would see a team of horses coming up the road home; my parents? are they coming to visit me? No. No. They never come to visit me. They never.”

“You’re wondering when the supervisor is going to come and haul you out of bed and take you to his room. Your turn come. Sleeping under the sheet. Wide Awake. You’re in fear, day and night in a place where I went to school. Punishment was very severe. They just did not strap you on the hands. They took your pants off and they put four or five belts together and let you have it.”

“When I talk about residential school, I done hard time in residential school, hard time. Now today I look at it. It is a Roman Catholic organization. It wasn’t God. It wasn’t my God. It is the people that run that residential school that done that to me. It is the people that put these things in place for us Native people. I do not hold anyone responsible in this room for what I experienced. I’ve learned that I was a victim of the times. I was punished for who I was, not what I did.”

“Years later on, what 6, 7 years ago, I did have a chance to take my abuser, my physical abuser, to court. For three days that I sat in the court room, them three days I was in there, I felt sorry for that man that we were trying to convict. I felt sorry for him. And at that that bastard put me through hell.”

“I seen kids running away from that school, one of them not coming back, drowned in the river. What did they do? They tried to make it right. They tried to talk to us, you know, tried to…one of the worst things you could do in the school I went to was run away; you were severely punished. You made sure you felt the lickin’ when you got a licken’. That wasn’t enough. They made you kneel down for a week after, every spare period you got, every spare time you got.”

“I had a little brother when I left home. Winter of 65, I seen my mother and four other men going to church carrying a little white box; it was about 1:00. I ran across the road. I was going to ask my mother, whose remains? ‘Your little brother.’ That’s how I found out my brother was dead. We buried him. I went back to school. I was made to kneel in a corner for the rest of the day because I went out of bounds; I left.”

“They degraded me. They called me a savage when I first entered that school. When them bastards were through with me, I had no feeling. I couldn’t express myself. I couldn’t say I love you. I wanted to hurt people; I hated. I had two daughters, one would have been 40 now, … April 30th she would have been 40, my other daughter would have been 34. Not once in my life did I tell them girls I love them. I couldn’t. I didn’t know how. I was ashamed to. I gotta live with that for the rest of my life, not telling them. Because my dad never told me that.”

“I want you people to listen to me. Nobody listened to me when I was a little boy. [Breaks down.] Excuse me. excuse me. It took a long time for me to get where I am today.”

“For some 40 odd years I had this closed in me. All this stuff making me sick. Hate. Hate is no good for you. Hate is no good for you. The end result is bad. I used to hate. I was a lonely man. I didn’t want nobody to be in my little world. I used to chase them away. Anybody that cared for me, looked after me, I disrespected them. I come to this community just east of here, some 40 years ago, a placed called James Smith. I come there as a 14, 15 year old kid, very dysfunctional, mistreated people, abused people. Those are the things I’ve got to deal with, I’ve got to make right in my travels in my time, then my kids can learn, and feel and tell their children they love them, they care.”

[At the beginning] “I introduced myself by my Indian name. You know why I was emotional? I was number 70, that is what I was known at school.

____________________________________

Also, read Helen’s thesis which tells her story in more detail (“My story, p. 37): Damaged Children and Broken Spirits: An Examination of Attitudes of Anisnabek Elders to Acts of Violence among Anisinabek Youth in Saskatchewan

___________________________________________________