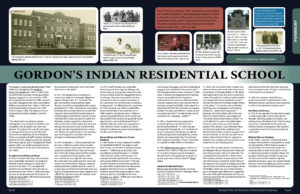

Gordon’s Indian Residential School

Gordon’s Indian Residential School

The Gordon’s Indian Residential School (1888-1996) was managed by the Anglican Church of Canada from 1876 to 1946. It was located on the boundary of George Gordon Reserve (Treaty 4) as a Day School in 1876 (established by Rev. J Reader, C. E. who went to the Pas in 1880 and was replaced by Mr. Settee “a pure Indian, who is a clergyman of C.E.” Indian Affairs Annual Report, 1880 ), and expanded for boarders in 1888. Gordon’s was later managed by the Indian and Eskimo Welfare Commission from 1946 to 1969, and by the Government of Canada from 1969 until its closure in 1996. The Anglican Church continued to provide chaplaincy into the 1990s. The school was destroyed by fire on February 1, 1929 and reopened in 1930.

An account of the freezing death of Andrew Gordon

Leaderpost, Regina, Wednesday March 15, 1939: Article regarding freezing death of Andrew Gordon.

Leaderpost, Regina, Wednesday March 15, 1939: Article regarding freezing death of Andrew Gordon.

“Neither young Gordon’s parents nor police knew of his disappearance from school [on Saturday] until visitors brought news to Mr. and Mrs. Gordon on Monday evening. Mr. Gordon started out to search for the boy Tuesday morning, and in the afternoon found the frozen body in the woods a mile from home and seven miles from the school.”

…Saskatchewan was recovering Wednesday from the fierce blizzard that swept the prairies Monday, but the mercury had skidded far down the tube to the lowest point in weeks.

An account of the drowning deaths of Myrtle Jane Moostos and Margaret Bruce in 1947

Acting Principal Wickenden’s account of the drowning deaths of Myrtle Jane Moostos and Margaret Bruce (1947)

Student strikes principal on head with a board

Whole school down with influenza

Punishment: extended residence for running away

______________________________

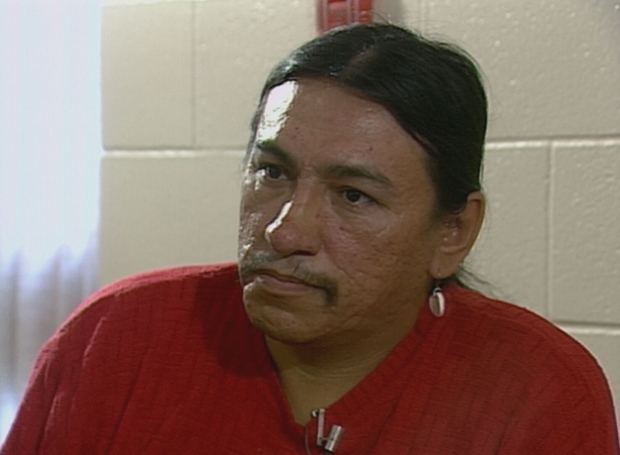

Convicted sexual abuser

In 1968, William Peniston Starr was appointed director of the Gordon Residence. It was a position he held until 1984.287 Starr had previously been the principal of the Anglican school at Fort George in Québec, and on the staff of the Anglican school in Cardston, Alberta.288 In 1956, he had worked as a physical training instructor at the Gleichen school in southwestern Alberta. He left the school after an unidentified conflict arose between him and the senior boys. According to a letter from Indian Affairs official W. P. E. Pugh, the conflict centred on the activities of the “gymnasium tumbling team he had been training.” The conflict was resolved by transferring Starr to another school.289 During his residential school career, Starr collected numerous positive evaluations. An Anglican assessment of his work from early 1954 noted, “Nothing but good reports of this worker from Mr. Pugh, the Bishop and the Cadet authorities. Under his leadership the Cadets did remarkably well at the Annual Inspection in Strathmore and his gymnasium team goes all over the country putting on demonstrations.” 290 Later that year, it was thought that it “might be a good move to make him vice-Principal or Assistant Principal when a new man is appointed.”291 Under Starr’s administration at Gordon’s, the residence became well known for its cultural and sporting organizations. The Gordon Dancers, for example, travelled across Europe. The school also had a highly regarded boxing team. Starr resigned in December 1984. At the final meeting of the Gordon Student Residence Advisory Board, he was thanked by the chair of the board for “his many years of hard work.” He, in turn, thanked the board for its “moral support.”292

Throughout his time at the school, Starr had been using his position to sexually exploit students. He instituted a system of bribery and intimidation to establish a regime under which he could sexually assault students. Those who refused to participate were punished through the denial of privileges.293 He was arrested on March 5, 1992, on twelve charges relating to sexual and child abuse, all arising from the years that he worked at the Gordon Residence. According to an internal government document at the time, “the department had not received any complaints relating to sexual or other abuse” during the time that Starr was employed at the residence.294 On February 2, 1993, Starr pleaded guilty to ten counts of sexually assaulting ten boys between the ages of seven and fourteen while he was the administrator of the Gordon Residence.295 He was sentenced to four and a half years in jail.296

Under Starr’s administration, there had also been continual staff and student problems. In 1972, a thirteen-year-old boy who had been convicted of indecent assault was committed to the care of the Saskatchewan Minister of Social Services for a one-year period, with the understanding that he “be sent to the Gordon’s Residential School to be with his brother and sisters.”297 In 1975, Starr reprimanded a residence employee, instructing him not to take students out of the residence, “whether it be for weekend visits, days off or miscellaneous activities,” without his approval. The employee was also forbidden to have students in his private staff room. Starr had issued these orders in light of “unfavourable gossip” regarding the staff members’ “drinking and homosexual activities” among students in the Yorkton area.298

The problems that Starr had fostered at Gordon’s continued after his resignation. In October 1988, a girl complained that the night watchman had made improper sexual advances to her while she was suspended from the school.299 He was suspended from his job and convicted of touching a person under the age of fourteen for sexual purposes and setting traps to cause bodily harm. He was fined $300.300 (The History, Part 2: 1939 to 2000, Vol. 1, pp. 447-448)

___________________________

Survivor Stories

Historica Canada podcast on Residential Schools

_________________________________________________________

One student, who attended the Gordon’s, Saskatchewan, school, recalled the ways in which the churches competed against one another to recruit students.

“But when we look at the residential schools, you know, and the churches we recognize, you know, at least I’ve seen it, you know, that we’ve had these two competing religions, the Anglican and the Catholic churches both competing for our souls it seemed. You know, I remember growing up on the reserve here when they were looking for students. They were competing against each other. We were the prizes, you know, that they would gain if they won. I remember they, the Catholic priests coming out with, you know, used hockey equipment and telling us, you know, “Come and come to our school. Come and play hockey for us. Come and play in our band. We got all kinds of bands here; we got trombones and trumpets and drums,” and all that kind of stuff. They use all this stuff to encourage us or entice us to come to the Catholic school. And then on the other hand, the Anglicans, they would come out with what they called “bale clothes.” They bring out bunch of clothes in a bale, like, a big bale. It was all used clothing and they’d give it to the women on the reserve here, and the women made blankets and stuff like that out of these old clothes. But that’s the way they, they competed for us as people.” (Survivors Speak, p.16-17)

_____________________________________

Emily Kematch was sent from York Landing in northern Manitoba to the Gordon’s school in Saskatchewan. When she was put on the train that was to take her there, she did not know she was being sent to school. “I didn’t know I was going away to school. I thought I was just going for a train ride and I was just excited to go. My sisters and my brothers were on the train too and I felt like, I have family with me, but I didn’t understand why my parents didn’t come on with us. They were just on the side of the railway there and they were waving at us as the train was moving away. And I remember asking one of the kids from back home, “How come our parents aren’t coming?” and then she said, that girl said, “they can’t come ’cause we’re going to school.” And I was talking to her in Cree and I said, “Well, I don’t want to go to school, I’d rather stay home and stay with my parents.” And she said, she told me, “No, we can’t, we have to go and get our education,” and then at night as we were travelling along, I got really lonesome. Because her siblings were going to the Anglican school in Dauphin, they got off there. Emily stayed on the train. “We were on the train, I’d say, like, three days to get to Saskatchewan and when we got there, three of my cousins were with me, those were the only ones I knew three boys, there’s Billy, Gordon, and Nelson and I was the only girl from my hometown.” (Survivors Speak. pp. 26-27)

When Emily Kematch arrived at the Gordon’s, Saskatchewan, school from York Landing in northern Manitoba, her hair was treated with a white powder and then cut. “And we had our clothes that we went there with even though we didn’t have much. We had our own clothes but they took those away from us and we had to wear the clothes that they gave us, same sort of clothes that we had to wear.” (Survivors Speak, p. 38)

Emily Kematch said one of the things she learned at the Gordon’s, Saskatchewan, school was “how to clean.” As a result, she said, I’m good at making a bed. We were taught how to make a bed perfectly. How to fold it, like each corner had to be folded just right and tucked in under the mattress, like the bottom sheet and then we put another sheet on top and our blanket. They were called fire blankets back then and our pillow and they had to be just right, or we’d get punished, if our beds weren’t fixed just right. (Survivors Speak, p.81)

Some students, however, spoke favourably of residential school food. One student, who attended the Gordon’s, Saskatchewan, school in the 1950s, said, “You know, I’ve heard a lot of people say that, you know, their experience in residential school, their meals were terrible. That wasn’t so in Gordon’s. Gordon’s provided really good meals, a lot of times they were hot, good meals.” (Survivors Speak, p. 77)

________________________________________

Shortly after Ben Pratt started attending the Gordon’s, Saskatchewan, school, the residence supervisor, William Starr, asked him if he wanted to work in the school canteen. He agreed, since it was a way of making some extra spending money. However, after a short time on the job, he was invited into Starr’s office.

And I remember after that evening, he took me into his office, and there was about five or six of us boys in there, and he started touching us boys. Some would leave, and some would come back, some would leave and come back when we’re watching TV in the back of his office. He had a couch in there, and a TV. And we’d all get ready to go to bed, and he made me stay back. And at that time, I didn’t know what was gonna happen. I was sitting there, and I was wondering how come I had to stay back, and I was watching TV there, and then he start touching me, and between my legs, and he pulled my pyjamas down. And the experience that I went through of him raping me, and I cried, and I yelled, but it didn’t do any good, ’cause he shoved the rag in my mouth, and he was much stronger than me, he held me down, and the pain and the yelling that I was screaming why are you doing that to me, there was no one to help me. I felt helpless. And after he finished doing what he did to me, he sent me back to my room, and I was in so much pain I couldn’t even hardly walk, and I could feel this warm feeling running down the back of my leg on my pyjamas and on my shorts. And I went to the washroom. I tried to clean myself up. This was blood. Starr organized a variety of extracurricular clubs to justify taking students on field trips.

According to Pratt:

We went all, all over, Saskatchewan, and dancing powwow, and going boxing, be different places, cadets, but it still continued to happen. As we were travelling in the vehicle, we always had big station wagons, or a van, and he fondled us boys. All of us boys knew what was happening, but none of us ever spoke about it, or shared anything what happened to us. We were too ashamed, too, too scared. Percy Isaac, who also lived in the Gordon’s residence, recalled how Starr would first win the confidence of the students he intended to abuse. Like paying us off, paying us off when we worked the canteen. Paying us off when we’d work the bingo. Paying us off to do any kind of things which he had. Like he had a boat, he had skidoos, he had all these different kind of gadgets, cars, let us drive cars when we were underage, we were driving a car. He too recalled how field trips were both rewards and opportunities for abuse. “Abused, abused in hotels, motels, all over the damn place. Toronto, Ottawa, you name it. Finland, went to Finland, got abused over there, you know. I was just constantly abused, sexually abused from this man. It was horrible.”

In 1993, William Starr was convicted of ten counts of sexually assaulting the Gordon’s residence students. (Survivors Speak, pp. 158-159) “But those convictions do not come close to reflecting the horrible scope of Starr’s alleged activities: of the 230 Gordon school plaintiffs who received a federal settlement, all claimed to have been abused by Starr” (https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/residential-church-school-scandal/)

He too recalled how field trips were both rewards and opportunities for abuse. “Abused, abused in hotels, motels, all over the damn place. Toronto, Ottawa, you name it. Finland, went to Finland, got abused over there, you know. I was just constantly abused, sexually abused from this man. It was horrible.” (Survivors Speak, pp. 158-159)

In Ben Pratt’s case, a laundry worker at the Gordon’s residence realized that something was wrong and asked him what had happened. Pratt initially resisted telling her, but then he explained how William Starr had abused him. “The look on her face she was angry, but she never said nothing.”

When he was an adult, Pratt told his mother about the abuse that he and other students were being subjected to at Gordon’s.

And she screamed, and she started crying, and I continued telling her what was happening when I was there. And the look on her face, the anger and the rage that came out of her, she screamed and yelled, and she went quiet for a long time, and this is the first time I ever had talked to my mother. She went calm for about fifteen, twenty minutes. And she said, “My boy,” she said, “the school I went to, when I was a young girl,” she said, “I, too, was sexually abused,” she said, “by the fathers.” And I asked her, “What school did you go to, Mom?” She said, “St. Philips.” I didn’t know where it was. And the things she told me that happened to her as a girl, from the fathers that run the school or worked there, the anger that came up inside me was so painful. I bent over, and I couldn’t sit up straight, how much anger and rage I had inside when she was telling me what happened. We talked for a good half-hour to an hour, me and my mother. Then it’s the first time I ever heard my mom tell me “I love you, my boy.” (Survivors Speak, p.161)

To the extent that they could, many students tried to protect themselves and others from abuse. At the Gordon’s school in Saskatchewan, the older children tried to protect the younger ones from abuse at the hands of the dormitory staff. Hazel Mary Anderson recalled, “Sometimes you’d get too tired to stay up at night to watch over them so nobody bothers them ’cause these workers would, especially night workers would bother the younger kids. The younger kids’ dorms were next to the older girls’ dorms.” (SS, pp. 162-163) Some students ran away from school in an attempt to escape sexual abuse. Hazel Mary Anderson and her sister found the atmosphere so abusive at the Gordon’s school that they ran away so often that they were transferred to the Lestock school. (Survivors Speak, p. 163)

____________________________________________

In January 1956, Albert Fiddler, a Gordon’s school student, wrote to his parents that he wanted them to take him out of school. He said the principal had kicked him and told the boys that they “weren’t fit for the school and he also said we might as well go back to our old reserves and live a rotten life.” He said he felt the principal and the supervisor did not like him and worked him too hard.215 In response to a query from Indian Affairs, the principal, Rev. A. Southard, wrote that Fiddler suffered from a “‘father on the council’ attitude towards the staff and was one of the four laziest students in the school. (Vol 1/2. p. 146)

Canada’s Residential Schools: The History Part 2 of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Final Report states, “In 1981, a student attempted to hang himself with a belt.” Lorne Pratt, has now spoken about this incident. “Pratt looks out the window and remembers the evening when as a 12-year-old student, he tried to commit suicide on the second floor of the old brick residence—the only way he could think to escape the constant sexual abuse he suffered over a five-year period. Now 32, an elegant man with high cheekbones and deep, sad eyes, Pratt recalls how he wrapped an elastic belt around his neck and hanged himself from the metal frame of his bunk bed, feeling the elastic pull, struggling for breath, finally blacking out. He was saved when school employees cut him down and rushed him to a hospital in Regina, where he remained in a coma for five days. When he was finally discharged, he was sent home to his mother, Leona, in Saskatoon – never to return to the school. ‘It was,’ Pratt says, ‘the happiest day of my life.'”(http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/residential-church-school-scandal/)

_______________________________________________________

___________________________________________

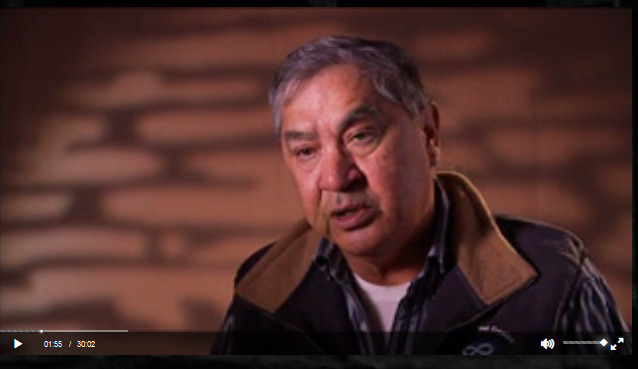

Darwin Blind, 61

Involvement” Student, Gordon Indian Residential School, Sask., 1954-1963

Currently: Family support worker, Gordon Wellness and Therapy Centre, George Gordon First Nation, Sask.

I spent nine years in a residential school. I was six years old when I went. My parents had no choice.

… My first experience was getting in a line-up of several children my age and being doused with louse oil. They believed every first nation person who came to school was filled with lice and diseases.

Many children like myself suffered physical, mental, emotional and sexual abuse. There was nothing ever mentioned at that time in regards to abuse. It was kind of accepted as the norm.

… [We were strapped]for anything. Anywhere they could hit you. It didn’t matter if you had a shirt on or not, those straps left marks. I’ve got scars on my body that I’ll die with.

Most of the [sexual abuse]happened at night in the dark in the big, crowded room or when you went to the bathroom. When you’re six … you’d go to the bathroom several times a night.

I’m very lucky though. I’ve been sober and straight for almost 25 years of my life.

Jamie Komarnicki The Globe and Mail

_________________________________________

Running Away

By Geraldine Sanderson

Gordon’s Indian Residence is an Anglican Institution. When I attended there, students were confirmed when they reached age 13. It was a really big deal. Everyone was confirmed.

I attended school at the Gordon’s residence from 1959-1964. I was nine years old when I started there. Every year a big bus would come to pick us up at the reserve and take us to the school. It took over three hours to get to Gordon’s from the James Smith Reserve. It was a long way from home. I was a very little girl. I got very lonesome.

Every once in a while students would run away, trying to get home. They would travel at night, helping themselves to vegetables and fruit from gardens along the way. One time we even took a pony from a farmer’s yard and rode it for several nights trying to get home. We hardly ever made it home, we were usually caught. And then we were punished.

Punishment for running away varied. One boy was hauled up in front of all the assembled students by the principal. He had a reputation for being mean. He forced the boy to pull his pants down and gave the boy 10-15 straps with a great big leather strap. Girls often had their head shaved bald if they tried to run away so that everyone would know. It was awful. I felt very ashamed. We also had to scrub the stairs with a toothbrush.

I left the student residence when I was 14 because my dad had passed away. My mother brought all of us children home. We stayed there for one year, and then she sent us to foster homes.

http://allaboutresidentialschools.weebly.com/personal-stories.html

______________________________________________