In June, the Faculty of Education launched the inaugural Gabriel Dumont Research Chair in Métis/Michif Education. Dr. Melanie Brice was appointed to the Chair for a 5-year term. With the establishment of this new Chair, the first in a Faculty of Education in Canada, and many other endeavours toward Truth and Reconciliation, the Faculty continues to demonstrate a concerted and sustained commitment to teaching and research that is engaging faculty, students, and other education stakeholders in gaining a deeper understanding of our shared histories and a reconciliatory approach to a more just future.Dr. Melanie Brice’s upbringing as a Michif (Métis): “A Culture of Place”

In June, the Faculty of Education launched the inaugural Gabriel Dumont Research Chair in Métis/Michif Education. Dr. Melanie Brice was appointed to the Chair for a 5-year term. With the establishment of this new Chair, the first in a Faculty of Education in Canada, and many other endeavours toward Truth and Reconciliation, the Faculty continues to demonstrate a concerted and sustained commitment to teaching and research that is engaging faculty, students, and other education stakeholders in gaining a deeper understanding of our shared histories and a reconciliatory approach to a more just future.Dr. Melanie Brice’s upbringing as a Michif (Métis): “A Culture of Place”

Dr. Melanie Brice, a Michif (Métis) born in Meadow Lake and raised at Jackfish Lake, Saskatchewan, has a strong understanding of Indigenous histories, cultures, languages and literacies, perspectives, educational experiences, and cross-cultural education issues. However, Melanie didn’t start out with this understanding. “SUNTEP was pivotal in helping me see how all my experiences growing up were an important part of my identity. I knew that I was Métis and what that meant. With SUNTEP, I learned how to integrate these understandings into my teaching and how to explain them to others.” says Melanie.

“Most of my childhood recollections are around time spent at my grandparents’ ranch, north of Meadow Lake. I had a charmed childhood, living at the lake, and spending holidays at the ranch, riding horses and playing with my cousins,” says Melanie. Her family had instilled values that she understands as Métis: “I was always told, ‘Be proud. We are hard-working people.’ And constantly reminded that family is important,” says Melanie.

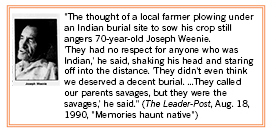

Genealogy is another interesting aspect of her Métis upbringing. Because Melanie is fair, her grandfather used to call her “wapistikwaan,” meaning “white head” and she wonders if he talked a lot about their genealogy because he knew there would come a time when she would be questioned. “Interesting, with everything going on around identity fraud,” Melanie says. “One reason genealogy is part of Métis culture is because we are always asked to prove our identity. We didn’t have the same recognition, rights, or status around the Indian Act.” Quoting 20th Century activist and Métis, Howard Adams, she says, “We are the forgotten people.”

From her genealogy, Melanie mentions ancestors such as Cuthbert Grant Jr, “considered warden of the prairie, one of the Métis leaders when Métis people became political with the Battle of Seven Oaks,” says Melanie, and Cyprien Morin and his wife Marie Morin who were among the first to settle at Meadow Lake in the late 1800s. “Hearing these stories when you are young, you realize, this is who your family is.” Melanie says, “That family is large, with many people descending from Cuthbert in the south and Cyprien in the north. I have family everywhere—many cousins as part of a large extended family. There is kinship among community.”

When thinking about how her upbringing gave her a sense of belonging, Melanie quotes bell hooks calling this sense “a culture of place.” “All of those experiences growing up,” she says, “and knowing you are related to so many people, shapes your understanding of how you see yourself and your place in the world, and the willingness you have to get to know other people and work with other people.”

The Misconceptions Around the Term “Métis”

Misunderstandings and misconceptions exist around the term, “Métis.” Melanie says, “I get frustrated when I tell somebody I’m Métis and they automatically think that means ‘mixed’ or worse, the derogatory ‘half breed.’ We are a distinct people with a distinct culture. We are our own, not half of anything!”

A pan-Indigenous misconception of what it means to be Métis has also been an issue. Melanie says, “I’ve been questioned my entire life about my identity.” However, Melanie looks at the questions she is asked, “Not as a challenge but as an opportunity to be able to share with people what it means to be Métis,” she says, adding that there are many variables involved in claiming the identity, not the least of which is to have connection with your community. “We have a nation. I don’t say I’m a member of the Métis. I’m a citizen in the Métis Nation. There is more than just genealogy and being accepted by a community. You also need to give back,” says Melanie.

The Importance and Activities of the Gabriel Dumont Research Chair in Métis/Michif Education

Melanie feels excited and thankful about being the first Chair: “I’m thankful to the Dean and GDI. Without the work they did, this Chair wouldn’t be possible,” she says. There have been similar chairs in Métis studies, in history and Indigenous studies, but this is the first in education.

It’s important, Melanie says, because “of the impact that education has on change, changing lives, influencing how we see ourselves and others.” Melanie hopes to bring a stronger Métis presence into curriculum, “impacting future generations with what we have contributed and continue to contribute to education.” She is excited to engage with other Métis scholars across the country to understand their research and the work they are doing to affect Métis/Michif education.

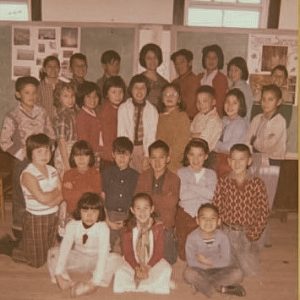

Another aspect of the Chair Melanie values is the opportunities it brings for enhanced academic engagement with GDI and SUNTEP. Melanie already has a long-standing relationship with GDI and SUNTEP as an alumna and former faculty while she was working on her PhD. She is excited that the Chair brings her back into teaching at SUNTEP. “Working with GDI and talking about what are some of the priorities right now, and how can we work together to achieve some of those priorities—That’s the really important piece: having something that responds to our community’s needs. The Chair can put those things forward.”

The Kaa-tipeyimishoyaahk–We Own Ourselves Project. Working around the issue of identity, one of the big projects that Melanie hopes to engage with as Chair is to research Métis/Michif Education. She says, “The word Kaa-tipeyimishoyaahk—We are a people who own ourselves (Gaudry, A. 2014)—was given to me by Michif elder, Norman Fleury. There has been a lot of research around Indigenous education. However, it is done in either a pan-Indigenous view or it is First Nations. There isn’t a lot of research on Métis/Michif learning. I definitely want to focus on bringing that into academia, supporting the teaching at SUNTEP.” The We Own Ourselves project is supporting this goal. Melanie is talking to elders and old ones, and Métis educators and scholars to find out what they need. She is also part of her own research project, learning northern Michif from a fluent speaker.

Language and Cultural Revitalization. According to the Statistics Canada 2016 census, with a rising population of 51.2%, the Métis were the fastest growing population in Canada between 2006 and 2016. However, less than 2% of Métis people speak the Michif language, making the Michif language one of the most vulnerable Indigenous languages in Canada.

Through the chair, Melanie intends to build capacity in Métis/Michif education by focusing on language and cultural revitalization along with research, learning, knowledge keeping, reconciliation, and inclusion.

Not everyone has had the same cultural experiences and opportunities as Melanie. Her daughters, whom she raised in the city, didn’t have the same experiences: “Even though I thought I did such a good job with my daughters, instilling in them a strong sense of their Métis identity, they didn’t have those kinds of lived experiences—cultural knowledge from being in community and at gatherings,” says Melanie. Over the years, Melanie has also seen a change in SUNTEP’s scope, in that when she went through the program, “SUNTEP taught Métis people how to be teachers. Now because of how successful colonization has been it is more like teaching students how to be Métis and how to be teachers.”

Melanie clarifies that the culture has not disappeared. “Culture is still there; it’s just not taken up in the same kind of way because of how families have moved away. That’s why it is important to be more explicit in terms of naming.”

Dreaming Big. Research on Métis ways of learning, knowing, and being is important; however, Melanie is concerned about the dearth of Métis researchers and PhD students. When asked to dream about the possibilities if unlimited resources were available, Melanie says she would like to see “fully funded Métis graduate students—students pursuing their PhDs without having to leave their communities or give up their income.” She recognizes that this would be tricky because there is value in doing a residency component; “Yet,” she says, “I can see where a move away from family and supports is a huge obstacle for potential students.” Another dream of Melanie’s is, “to adequately compensate our elders, old ones, and knowledge and culture keepers who are so pivotal to the research.”