Dr. Angelina Weenie is a Plains Cree from Sweetgrass First Nation in Treaty 6 territory.

Dr. Angelina Weenie is a Plains Cree from Sweetgrass First Nation in Treaty 6 territory.

My TRC story is not the typical story as I did not attend residential school; I went to Sweetgrass Day School. My parents attended Delmas Residential School. It is about 10 miles from our reserve. My two sisters and my brother attended Lebret Residential School. My other sister attended St. Gabriel’s High in Biggar, Saskatchewan. They each had different experiences. It is hard for me to write about others’ experiences. It is their story, and they are not here anymore. It is not my place to write about them, but they need to be honoured and not forgotten.

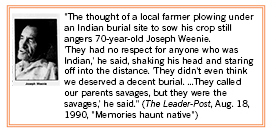

I do unde rstand why I carry a deep sense of loneliness and sadness. It must emanate from my parents and my brother and sisters and what they went through when they were taken from their families and from their homes. My father was interviewed by the Leader-Post in 1990. He talked about how the nuns would call them savages.

rstand why I carry a deep sense of loneliness and sadness. It must emanate from my parents and my brother and sisters and what they went through when they were taken from their families and from their homes. My father was interviewed by the Leader-Post in 1990. He talked about how the nuns would call them savages.

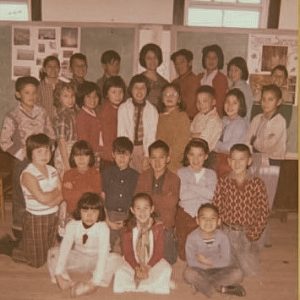

Lebret is far from our home (about a 5-hour drive). Sweetgrass is west of Battleford, Saskatchewan. I remember when the big yellow school buses would arrive to pick up the children. I can only imagine how lonely, lost, and scared they would be to go so far away from home. I also have a photo from my sister Lorraine’s Grade 12 graduation. My parents, my grandparents, and the principal from our school travelled to Lebret. This was a grand occasion for my family. My grandfather stood proudly in his chief’s outfit (See photos below).

These memories are about how First Nations people believed in education. Education has always been important to us. The outcomes were different in many situations but, ultimately, First Nations people wanted their children to succeed. Our parents instilled the importance of education in us and supported us. We come from a nation of proud and resilient people.

_______________________________________________________

Dr. Anna-Leah King is an Odawa/Potawattimi originally from Wikwemikong.

Dr. Anna-Leah King is an Odawa/Potawattimi originally from Wikwemikong.

When Angelina and I heard of the reveal of 215 unmarked gravesites at Kamloops, British Columbia’s former Indian Residential School (IRS) site, it affirmed horror for Indigenous survivors. In response, we hosted a feast at First Nations University (FNUC). This connected us as we knew we both had in one way or another the IRS experience in common and were pondering what to do and recognizing the sense of heavy spirit that was overtaking everyone. It was a positive and constructive measure.

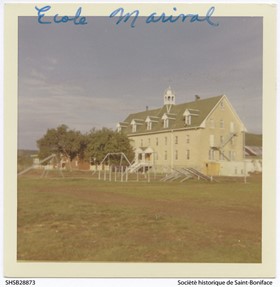

This news report was only the beginning. A short time later, at Marieval Indian Residential School on Cowessess Reserve, Saskatchewan, another ground-penetrating search was conducted, which found 751 gravesites. The IRS survivors were always aware these gravesites existed and the news was no surprise. Some survivors have shared their stories with each other and with others who did not attend a residential school, but have not always been believed, even by their own people. Being believed about their collective horrific experiences that took place at Indian Residential School has been a long time coming. Some shared testimonials with the Truth and Reconciliation commission. In fact, this is where the sharing of these gravesites began. The then Chief Justice Murray Sinclair recommended in the TRC Calls to Action to have ground searches done at every residential school across Canada to finally reveal these gravesites publicly (TRC, 2015). And so it began, ground searches across Canada, to the 139 Indian Residential Schools, to uncover gravesites verifying the tragic end of innocent children’s lives who came to their deaths at the hands of abusive nuns and priests. The stories of these now Keteyak (Old Ones) will never be forgotten.

I remember my Elder and dear friend, the late Laura Wasacase, sharing some of the experiences she and her friends encountered at the Indian Residential schools. Some women heard the babies cry at night but there were no babies in the morning. Some witnessed horrendous physical abuse. Some saw a fellow student “fall out” the second floor window to her death, learning later of the possibility that she was pushed because the next girl held on tight and prepared herself not to “fall out” when left alone with an angry nun.

These ground searches at Kamloops and Cowessess were the first of many that would take place across the country in every residential schoolyard. The grand tally will not be known until all the ground searches are completed. As of today there are 1,800 unmarked graves estimated of which former Chief Justice Senator Sinclair estimates numbers could be anywhere from 6,000 to 25,000. The heartache and pain of the survivors’ traumatic memories stirred up is no less for the survivors of the survivors.

I thought about my mother and father who attended Spanish Indian Residential School in Spanish, Ontario. It was run by the Catholic Jesuit Order. There were two school buildings: Garnier was the boys’ school and St. Joseph’s the girls’ school. My father had chosen building maintenance for his obligatory chore. He told me one day when I was a young adult how he recalled making the crosses for the boys that died there during the school year. He reflected on the insensitivity of the “black robes” as they callously informed the parents of the passing of their child in that school year. My parents never shared much of what took place there until late in life when more news stories frequented the print media. My mother was in her 70s when she first began to share experiences. She and my Auntie would recall “Bologna Legs” as they referred to a nun who was particularly cruel to them.

These schools ran from 1870s to 1990s and some were open for over 100 years (Restoule, 2013). The Canadian government and the churches aligned forces to “kill the Indian in the child.” Assimilation was their point and purpose by order of John A. McDonald. The truth was, they exercised genocidal practises on the children in every form of abuse possible. Although many priests have been reported for their sex offences towards children, only some have been charged. The United Church of Canada in Sudbury, Ontario was the first to publicly apologize in 1986 for the atrocious wrongs that were committed against Indigenous children at these schools. The same cannot be said for the Roman Catholic Church. Of the 130 schools, most of them were run by the Roman Catholic Missionary congregations. The Vatican refuses to apologize despite Justin Trudeau’s efforts in 2017. On September 24th, 2021, at the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops, an official apology was issued for their role in the IRS, succumbing to public pressure (Warburton, 2021).

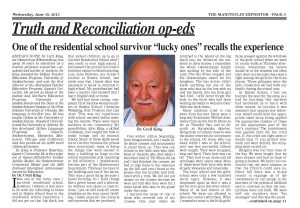

I conclude with my father, Cecil King’s, words with regards to reconciliation that he shared in a piece for the TRC. My father was encouraged to become a teacher in the 12th grade. This he did, spending 50 years in education as a teacher, professor, researcher, consultant and teacher of teachers. He is the creator and founder of the Indian Teacher Education Program (ITEP) and former Dean of the Saskatoon Campus First Nations University. My father advises to strive for “bonnigi deh taadewin” an Ojibwe phrase meaning “the process of pushing the badness out of your heart.” He suggests that everyone needs to get out of the dialogue of the mind and speak from our hearts, including politicians, bureaucrats, and the general population, before any true reconciliation can happen (2015, TRC).

Additional Note: Dr. Cecil King will be publishing his memoir titled: The Boy from Buzwah in February 2022 through the University of Regina Press.

Follow us on social media