If you are looking for the latest news for the Faculty of Education visit EduPulse: our Education eNewsletter.

If you are looking for the latest news for the Faculty of Education visit EduPulse: our Education eNewsletter.

Congratulations to Dr. Jaime Mantesso, one of two recipients of the spring 2023 Faculty of Education Associate Dean’s Graduate Student Thesis Award.

Congratulations to Dr. Jaime Mantesso, one of two recipients of the spring 2023 Faculty of Education Associate Dean’s Graduate Student Thesis Award.

The Faculty of Education Associate Dean’s Graduate Student Thesis Award was established in 2021 to recognize outstanding academic performance of thesis-based graduate students (Masters and PhD) in Education. This $2,000 award is granted to a student in a graduate program in the Faculty of Education who has exemplified academic excellence and research ability, demonstrated leadership ability and/or university/community involvement, and whose thesis/dissertation was deemed meritorious by the Examining Committee.

Mantesso successfully defended her dissertation titled, “Understanding How Saskatchewan Parents Promote Their Children’s Mental Health: A Grounded Theory Study” July 18, 2022. Her supervisor was Dr. Marc Spooner and committee members were Dr. Twyla Salm, Dr. Kristi Wright, and Dr. Val Mulholland.

The external examiner was Dr. Charlotte Waddell. And Dr. Maria Vélez chaired.

Mantesso is a registered nurse and works in the Faculty of Nursing at the University of Regina.

Mantesso chose to study children’s mental health, focusing on parents because, she says, the topic “was important to me firstly because I am a parent of two boys.” She also found that, “While lots of information was available about risks factors to avoid and how to identify mental disorder symptoms, I found little scholarship detailing ways in which parents could best promote their children’s mental health. Studying mental health from a salutogenic perspective meant that I could focus on what the precursors to mental health are and how parents can exploit them.”

As she moves forward, Mantesso says, “I would like to continue build on some of the theory and findings from my dissertation. I really enjoyed my doctoral experience and hope others decide to undertake advanced education through the Faculty of Education — it is incredibly rewarding!”

On Monday, June 19, 2023, the raising of the Flag of the Métis Nation on the University of Regina campus was celebrated with a ceremony organized by SUNTEP Regina (Gabriel Dumont Institute ) with the ta-tawâw Student Centre under the leadership of SUNTEP Program Head Jeannine Whitehouse. The flag is located across from the Treaty 4 Flag in the hallway by the ta-tawâw Student Centre.

Opening prayer and blessings were offered by Knowledge Keeper Irma Klyne with remarks by Dr. Jeff Keshen, President and Vice-Chancellor of the University of Regina. Métis fiddler Tahnis Cunningham played a song of celebration. Following the ceremony, Janette Grams provided a traditional meal of soup and bannock.

“The Gabriel Dumont Institute and the University of Regina have a partnership that has been in place over 40 years. We were honoured to host this flag raising event in partnership with the ta-tawaw Student Centre. On this day, June 19, 1816 Métis leader Cuthbert Grant flew the Métis flag for the first time at la Victoire de la Genouillère and declared la nouvelle nation (the new nation). Flags are important symbols uniting a nation’s people. Flags often provide a way for people to recognize or identify a place and see themselves belonging in spaces. Having the Métis flag in this space honours Métis students and staff here on the U of R campus.” Jeannine Whitehouse, SUNTEP Regina, Program Head.

Congratulations to Dr. Uwakwe Kalu, one of two recipients of the spring 2023 Faculty of Education Associate Dean’s Graduate Student Thesis Award.

The Faculty of Education Associate Dean’s Graduate Student Thesis Award was established in 2021 to recognize outstanding academic performance of thesis-based graduate students (Masters and PhD) in Education. This $2,000 award is granted to a student in a graduate program in the Faculty of Education who has exemplified academic excellence and research ability, demonstrated leadership ability and/or university/community involvement, and whose thesis/dissertation was deemed meritorious by the Examining Committee.

Kalu successfully defended his dissertation titled, “Intergenerational Knowledge Transfer in Traditional Herbal Medicine (THM) Practices among the Igbo Tribe in Nigeria: A Qualitative Study” on July 11, 2022. His Co-supervisors were Dr. Abu Bockarie and Dr. Douglas Brown. Committee members were Dr. JoLee Sasakamoose, Dr. Anna-Leah King, and Dr. Florence Luhanga. The External Examiner was Dr. Ranja Datta.

In his doctoral research, Kalu explored the “assertion that traditional herbal medicine (THM) has been a reliable source of health to Africa before colonization, which raises pertinent questions about how the THM knowledge was acquired, sustained, and transferred before colonial incursion.”

“One cannot talk about intergenerational transfer of knowledge without recourse to the role of learning/education in knowledge acquisition, preservation, and transfer, which makes education and intergenerational learning co-constitutive in the study. The study concerned itself with the role of learning in the intergenerational transfer of THM practices among the Igbo tribe in a postcolonial Nigerian society,” explains Kalu.

Fieldwork for the study was conducted during the period when the world was on lockdown due to the ravaging effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic led to a global call for robust health care services to tackle the menace. Kalu says, “Therefore, there is the need to preserve, promote, and transfer the knowledge and practices of traditional herbal medicines (WHO, 2009), and my hope was that the study would contribute to the implementation of the WHO decision on promoting THM practices among Indigenous communities, Igbo society in particular.”

Kalu had several reasons for choosing his research topic: “Firstly, I embarked on this journey as part of my ‘little’ contributions toward decolonizing Indigenous practices. Secondly, I conceived the idea of the research topic during the heat of the Covid-19 pandemic while helplessly watching people die daily in thousands, globally. Thirdly, it is a product of psychological and emotional bewilderment exacerbated by the defencelessness of reliance on Western medicine alone for global health care needs. Finally, it is part of my contributions towards facilitating robust global healthcare services by revamping traditional medicine practices.”

Kalu currently works for Creative Options Regina. Because Kalu found the Faculty welcoming, he says, “I have already been recommending people to take their program with the Faculty of Education.”

By Gertrud Bessai

It is important to remember how the Faculty of Education all started not so very long ago! Here is the life story of someone who was instrumental in the development of the Faculty.

Fred Bessai, BA’58, BEd’60, MEd’62, PhD’64, Fellow of the Royal Society in London

Fred was born November 9, 1932 on the family subsistence farm near Southey, Saskatchewan. He was the second son and fourth child. At home both parents and children spoke a Germanic dialect and in school the children learned English. Fred’s parents were multilingual and could easily talk with the Romanian and Ukrainian speaking neighbours. At 5 years of age, Fred entered the nearby one-room school where he did so well that he skipped a grade somewhere along the way. The school only offered Grades 1 to 10 and so he decided to to earn Grades 11 and 12 through correspondence, four classes at a time while working on farm. During this time he and his younger brother cleared a fairly large piece of land of a huge number of stones. The first crop off that land paid for a year at Teachers’ College in Moose Jaw. Fred managed to land a job teaching in a one-room school fairly close by and so was able to return home daily and continue to help out on the farm. Following in his elder brother Frank’s footsteps, Fred went off to study at the University of Saskatchewan after having taught in various schools. He entered the arts program and graduated with a BA in 1958. Summers were spent sieving and testing bearing capacity for the Department of Highways. But then disaster struck! His younger brother died and Fred had to hurry back home. By this time his father was ailing! The decision was made to move their parents into Southey and to convert the farm to a strictly wheat farm. Fred was able to do the seeding, and the pasture was rented out, while spraying and summerfallow was accomplished with the help of others. After their parents were settled, Fred went back to work for the Department of Highways, this time as inspector, to earn enough to continue with his education. After harvest, it was back to Saskatoon, to enrol in the College of Medicine. But, medicine proved to be the wrong choice! Fred returned to the farm at end of term. The income from the farm had to support his parents! But his need to further his education was huge, so Fred worked out a system to accomplish both. 1960 saw his graduation with a BEd and a trip to Europe where Frank, was working on his PhD in English. While there they looked up their father’s relatives who had made their way from the Bukovina/Roumania to Germany. They also found their mother’s mother in East Germany and managed to get her out and ultimately to Canada! Back in Canada, Fred enrolled in a master’s program with the help of a scholarship provided by the Saskatchewan Teachers’ Federation. During that time he met Gertrud von Gernet, who later became his wife. With the Master’s finished in 1962, Fred looked further afield for a PhD. Since Frank was now teaching English in Edmonton, Fred decided to try his luck there. The Dean offered a teaching fellowship. With his livelihood secured, Fred threw himself into studies and teaching. But the farm still needed attention, and so he drove home to seed, arranged for spraying and summerfallow, drove back for summer classes, and then returned for harvest and to sell the crop. This pattern of academic life and farm life ended up the pattern for his entire life.

In the summer of 1964, with the thesis completed and accepted, he was hired by Dr. Lester Bates, dean of the newly formed College of Education in Regina. The teachers from the Teachers’ College in Moose Jaw joined the Arts and Science professors in Regina to form the new junior campus of the University of Saskatchewan. In the beginning there were three PhDs in the Faculty of Education: Dr. Bates, dean; Dr. Buck, formerly head of the correspondence school; and Fred! The rest of the faculty were Fred’s former teachers. Since he was the youngest and most familiar with the current research, he was tasked to help develop the Education library. Then, when the new campus was being built, he was delegated to help design the new Education building. All the while he was teaching whatever classes seemed to be needed in his field: measurement, early childhood education, and finally research. He worked hard to get the master’s program on the books and finally started the PhD program. During this time he was also the Education delegate to Saskatoon when the Regina campus wanted to separate and become an independent university.

Many of his former teachers and others wanted to upgrade and Fred was always ready to lend a helping hand. But his greatest joy was to help the young teachers to earn their master’s degrees. It did not matter in which direction their interests lay, he was there to ensure that they learned the all important methods of research and writing. He kept up with the most recent research by attending NCME and Learnet Society. Meanwhile, the farm was looked after on weekends and during holiday time. The only time he took a sabbatical was to go to Prince Edward Island, where a perfect “lab” situation had materialized. The small one-room schools were to be replaced by large consolidated ones. What was the learning environment? How well did students fare? The result was a book authored by Dr. Edward L. Edmonds, dean and Dr. Frederic Bessai (1979). Fred spent his entire career at the University of Regina, although he was offered several other positions including a deanship. His two great loves: teaching and farming kept him here. Today he has celebrated his 90th birthday, and still enjoys reading about the history of the province and reminiscing about days gone by!

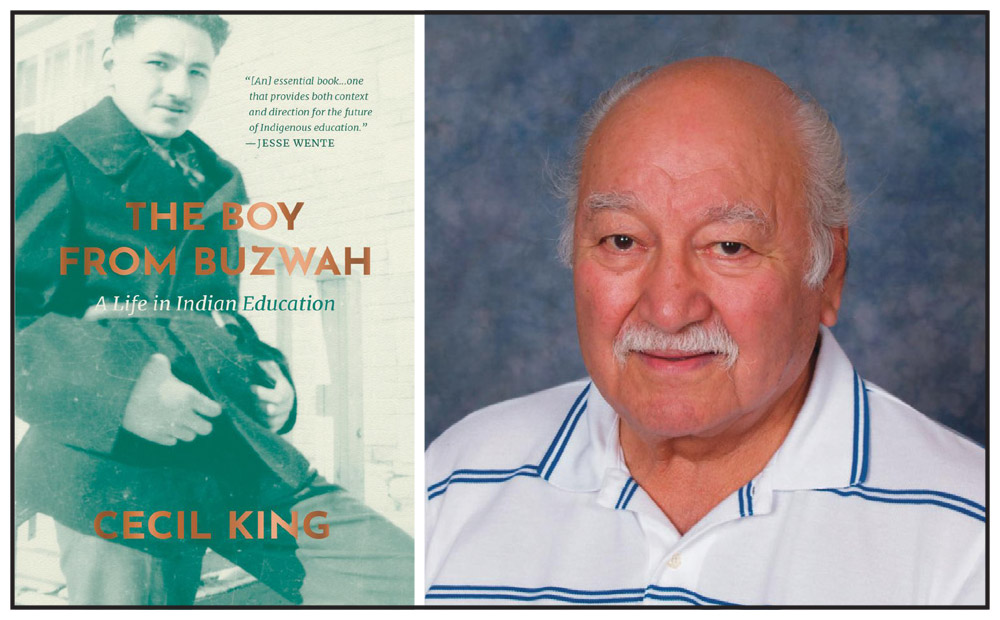

The footsteps of ancestors, family, and mentors have guided Dr. Anna-Leah King in her life-journey. Anna-Leah is Anishnaabe, an Odawa on her father’s side, the late Dr. Cecil King, and a Pottawatomii on her mother’s side, the late Virginia (Pitawanakwat) King. The name stories behind these nations are outlined in Anna-Leah’s father’s recent memoir, The Boy From Buzwah: A Life in Indian Education: Cecil wrote, “My grandfather maintained that in the beginning, there were three biological brothers—Odawa, Pottawatomii, and Ojibwe. Over the years, they went their separate ways, and as a result, three separate nations were formed—the Ojibwek, the Odawak, and the Potawatamiik,” called the “Confederacy of Three Fires—the Anishnaabeg,” a word which means, “I am a person of good intent or I am a person of worth” (pp. 1–3). These stories form the core of Anna-Leah’s identity.

Like her parents, Anna-Leah spent her early years on Manitoulin Island (Island of the Great Spirit) in Northern Ontario, surrounded by family, culture, Ojibwe language, and history. Her early experiences have lingered and wafted throughout her journey, like campfire smoke in a sand plain forest, imprinting her worldview.

Anna-Leah’s father was a major influence in her life. He blazed the trail for many of the professional choices she has made. Even though teachers are part of her blood line—her great grandmother and father were teachers—Anna-Leah didn’t like school, and didn’t see herself becoming a teacher: “I never saw myself as a teacher. When I was in my younger grades I swore to God I would never be a teacher. I found schools unwelcoming places, aesthetically dead places, with ugly muddy green and orange paint,” says Anna-Leah.

Aesthetics aside, Anna-Leah’s early experiences with some teachers were not positive either. She recalls a confusing and frightening experience in kindergarten, when she held out her hand for a reward and was instead strapped with a leather strap by her teacher.

Despite her dislike of school, Anna-Leah’s father encouraged her to become a teacher. And once, when he returned from one of his many trips, he brought Anna-Leah a miniature brief case. “It was just like his. That was the first seed planted, that when I grew up, I could be like my dad,” she recalls.

In 1969, when Anna-Leah was 6, her Dad took a job in Ottawa, where Anna-Leah spent the remaining years of her childhood. But in 1971, when her father moved two provinces west, to Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Anna-Leah determined she would follow in his footsteps: “I couldn’t wait to reunite with my dad some way, somehow.”

For her final year of high school, she (along with her sister Alanis) moved to Saskatoon to be with her father. Following high school, Anna-Leah decided to become a teacher and finished her teaching certificate in 1989 through the Indian Teachers Education Program (ITEP) at the University of Saskatchewan, where her father had been the founding director. Despite her early objections, she had become a teacher, like her dad. But the trail didn’t stop there.

Cecil was an Indigenous educator for more than 60 years. He had a tremendous impact on Indigenous education in Saskatchewan and impacted the lives of the many students he taught. His career took him from teacher, to principal, to professor, and into multiple leadership roles provincially and across Canada, mostly within the university context.

Cecil King’s Legacy: An Era of Indian Control of Indian Education

During the 60s, the political and social environment was developing into a storm following the adoption of a forced integration/assimilation policy, which threatened the continuation of Indigenous languages and culture. In his memoir, Cecil (2022) wrote, the Federal Government’s “Department of Indian Affairs was busy transferring education to local school boards…negotiating joint school agreements without the approval of individual First Nations” (p. 209). This colonizing policy resulted in more standardized and irrelevant curriculum and content in Indigenous schools that devalued and disregarded Indigenous worldviews and local Indigenous involvement. Cecil regarded the policy as responsible for the problem of, “Indian children achiev[ing] only limited education characterized by low education achievement rates, high failure rates, so called age-grade retardation and early school leaving” (p. 222). He maintained that pride in one’s identity was critical to success in life and education.

Cecil grew up in a bilingual, bicultural, multigenerational home where English was the only language spoken. His grandparents who raised him had been convinced by their Catholic schooling that English was the only path to success, and should be the language spoken at home. He had a well-rounded education at home: His grandmother who had been trained as a Victorian-era teacher, was a strict disciplinarian; his grandfather was a talented handyman, who taught Cecil how to do things but also transferred the Odawa history and worldview to Cecil; and Kohkwehns was his emotional support, who, Cecil says, “listened to me and taught me how to be a ‘good’ Odawa” (p. 323).

From Grades 1 to 8, Cecil was taught by First Nation teachers at the Buzwah Indian Day school and he learned to speak Ojibwe at school from his peers. He excelled at his studies: “At school we learned and communicated in English, and although what we read was foreign to us, we learned. … We didn’t read about First Nations history or heroes, but we lived among First Nations people and learned that part of our education from them” (p. 51).

When he had finished Grade 8, Cecil had to leave his home and community to attend a residential high school, St. Charles Garnier Residential School in Spanish, Ontario. Cecil, along with three of his peers, passed the entrance exams, and bid goodbye to their families and friends. Ominous black buses arrived each year to take the children to residential school. Cecil had mixed emotions about going, because he was leaving behind his family (and beloved Kohkwehns) and community and because he knew from experience that sometimes kids didn’t return home from residential school, but he was also excited and proud to be continuing his education.

At Garnier, he again excelled in his studies, despite being told that Indigenous culture was “quaint” and that students should not expect to rise to the pious level of the French Jesuits who taught them. Students developed a subculture where Cecil continued to learn and practice Ojibwe, and where they traded off items from their assigned work areas. “Recalling these things, I realize that this was our world. We created a culture within the institution’s culture. We found a way to circumvent the forces that dominated,” (p. 131) wrote Cecil. Cecil was valedictorian when he graduated in 1953.

After high school, Cecil took a 6-week course in order to take a teaching position at West Bay School on Manitoulin Island. The post-war baby boom was creating a demand for teachers. In 1954, Cecil married Virginia, whom he had met at residential school. He also took a second 6-week course and took another teaching position at Northwest Bay. At this stage in his career, he already had a drive to take on a principal role. The following year, he enrolled at North Bay Teachers’ College and became a qualified teacher by 1957, after which he was hired as a principal at Dokis Bay Indian Day School.

Cecil worked throughout his career to take back control of Indian education. He described this work as complex, involving the development of curriculum, teaching materials, lessons, and workbooks for teaching Ojibwe. Ojibwe teachers needed to agree on how the language would be written. Cecil wrote, “It became apparent that standardizing the written Ojibwe language was a necessary step in establishing a province-wide Ojibwe language teaching program. Here we ran into the debate over the appropriate orthography. Now we realized that to teach the language in the school we needed to have written language and material for the children to read. … Success in teaching Native languages in schools would be dependent on a teacher-training program specifically for teachers of Indian languages” (p. 182).

Working together with his cousin Mary Lou Fox-Radulovich, the two were successful at getting an Ojibwe language program approved for teaching in elementary schools. Trent University began offering a Teaching Ojibwe in Schools course that Cecil taught in 1970, delivering the course to non-Indigenous students.

There he met Dr. Art Blue who encouraged Cecil to enter full-time study at the University of Saskatchewan through the Indian and Northern Education Program (INEP). The decision was pivotal: “When I made the decision to go to Saskatchewan, I did not know that it was going to have a profound impact on my life” (p. 202).

The 1973 adoption of the National Indian Brotherhood policy statement on Indian control of Indian education, “sounded the death knell for the policy of forced integration policy and led to the establishment of on-reserve schools,” (Cuthand, 2013). At the same time, Cecil’s career was taking a dramatic turn—in his words, he was “joining the revolution” (p. 201). Little did he know that Rodney Soonias of Red Pheasant First Nation, who was the director of the Saskatchewan Indian Cultural College (SICC), had selected Cecil to be the founding director of the ITEP: “The new task was to design, develop and implement a program that produced Indian teachers who received the same credentials as other Saskatchewan teachers but who were equipped to change the education of Indian children in the province in accord with the wishes of the chiefs, communities, and parents while preparing children for their place in society” (p. 209). His decision to stay in Saskatchewan and take on this role came at a great personal cost: the permanent separation between him and Virginia. By that time, they had five children.

As director, he travelled to various Cree communities in Saskatchewan to establish pilot Cree language projects. Others were also establishing Indigenous language programs. Cecil wrote, “Everyone …was on side and working towards the same goal: to take control of education for First Nations people in Saskatchewan. The power, the force, the energy that was released was incredible” (p. 224).

After finishing his B.Ed. (’73) and M.Ed. (’75), Cecil began his PhD journey at the University of Calgary. In 1983, he was the first Indigenous Canadian to receive his PhD from the University of Calgary. During the 1980s, he was head of the Indian and Northern Education Program, which positioned him as a faculty member in the College of Education at the University of Saskatchewan. Cecil served on multiple dissertation committees at multiple universities including the University of Regina. After the program he headed was folded into the Foundations department and Cecil was denied promotion, he left the University of Saskatchewan and took a full professorship at Queen’s University where he became the founding director of the Aboriginal Education Program.

Looking back to Cecil’s 1953 valedictorian speech, the seeds of the vision that would characterize his career can be seen: Cecil said, “We all realize how advantageous it would be to have our own teachers, lawyers, doctors and politicians, men and women who will work hand in hand with those who now are working for our rights and prosperity. We need men and women who will be exemplary leaders in our own communities …men and women of vision, initiative and energy” (p. 138). Cecil himself became that exemplary leader, and a man of vision, initiative and energy. He cleared the trail for many who would also follow in his footsteps.

When Cecil passed away May 4, 2022, Doug Cuthand eloquently wrote, “At 90 years of age, the final school bell rang and he began his journey to the next world. King may have moved on, but his work lives on in the hundreds of teachers whose lives he touched”.

Dr. Michael Tymchak, former dean in the Faculty of Education at the University of Regina, and former director of the Northern Teacher Education Program (NORTEP) in La Ronge, says, “Cecil was a leader in Indigenous Education here in Saskatchewan, and across Canada. As Director of ITEP he broke trail for many other First Nation educators to follow. Cecil understood the corrosive impact of colonialism but his life spoke most eloquently to vision-casting and the creation of educational opportunities for First Nation students. He was a believer in self-determination and an advocate for the vital importance of preserving Indigenous languages and culture. Strong in his own Anishnaabe identity, he was unafraid of strategic ‘co-determination.’ Cecil knew that Indigenous peoples and their culture(s) had much to offer the larger society and he dedicated his life to manifesting this conviction.”

Dr. Tymchak continues, saying, “Cecil provided a role model for others to follow and was unfailingly supportive of the establishment of other Indigenous teacher education programs. During my years at NORTEP, Cecil offered enthusiastic encouragement, came up to La Ronge to teach courses and spoke to significant gatherings, such as the annual Graduation Ceremony. He was unfailingly eloquent and inspiring, a statesman and later a highly respected Elder. His passing leaves a void, but his legacy of accomplishments and the memories he leaves of kindness, educational leadership, and collegial friendship will endure as long as the sun shines and the rivers flow.”

Anna-Leah’s career path mirrors many of her father’s footsteps: She, too, chose to further her education with a Master’s degree and then her PhD (2016), which focused on reclamation of Anishnaabe song and drum in education. She was a recipient of the University of Alberta Human Rights Education Recognition Award in 2013. She served as the Co-Director of the Aboriginal Teacher Education Program (ATEP) at the University of Alberta from 2008 to 2010. And she now works as a professor of Indigenous education and core studies and has been serving as the Faculty of Education Chair of Indigenization at the University of Regina for the past several years.

Virginia King’s Legacy

While it is clear that Anna-Leah has followed in her father’s rather large footsteps, she also follows in her mother’s less visible but no-less-valuable footsteps. For instance, Anna-Leah recalls 3 days of cooking massive pots of soup and making heaps of sandwiches at her friend’s granddaughter’s funeral and wake. “I thought of my mom, she would have done the same thing. My mom was always bringing soup to the friendship center in her down time,” says Anna-Leah.

Throughout her career, Virginia worked with Indian Affairs, eventually working her way to the role of director, with signing authority on treaty cards. “My mom was really proud. When I was between about 6 or 7, I went to Parliament Hill and did a march with her. The night before, we were making a placard and I was to write: ‘Indian women are women, too.’ I thought how can people think Indigenous women aren’t women, too? Bizarre! I didn’t have that feeling myself. I always felt accepted, and there wasn’t a big cultural gap. We proudly marched. My mom wasn’t brave enough, but she made me hold the sign. And I knew there was activism to do,” says Anna-Leah.

As a residential school survivor, Virginia didn’t talk much about her experience until later in life, but, “she did realize the wrong that residential school did in trying to snuff out the language and the culture,” says Anna-Leah.

Though her parents could speak Ojibwe, they did not pass the language on to their children. Anna-Leah says, “My mom and dad had a conversation about not teaching us the language so we would be successful at school because my dad was seeing the kids come in to school and struggle and struggle and then get turned off and eventually drop out because they were always behind.”

Other Teacher/Mentors

Another woman was influential in Anna-Leah’s life, her auntie, the late Mary Lou Fox-Radulovich, a member of M’Chigeeng (West Bay) First Nation and founding director of the Ojibwe Cultural Foundation, an organization formed to preserve Ojibwe, Odawa, and Pottawatomii Nations’ culture and language. Mary Lou was a teacher and language activist who also inspired, supported and worked alongside Cecil King. Anna-Leah had the privilege of spending a summer with Mary Lou at the Foundation.

“My dad must have asked if she could take me on as a summer student. I got to go there, and live with my grandmother at Wikwemikong. I would travel 45 minutes to M’Chigeeng each day. When I got there, Mary Lou came and gave me a warm hug and a kiss. I think the first day we went sweetgrass picking, and then we braided the grass. She joined us in braiding, and talked about how beautiful it was to be outside, to enjoy the wind, and to braid sweetgrass in the company of other women. I think ancestral memory was part of that day for her. I felt in an indirect way she was teaching us the power of that exercise. I really loved that. I felt in tune immediately with the practice and what we were doing,” recalls Anna-Leah.

The rest of the summer was spent in preparation for an Elder’s conference. The braids they had made were for the Elders. Anna-Leah says, “I was honoured to be making those braids for the Elders. Mary Lou was connected to Elders all over Canada, because she was trying to do something about the languages and cultures.”

Anna-Leah continues, “I learned a lot from her and the girls I worked with. I learned where the sweet grass grows. I learned to wear rubber boots, to not be afraid of anything that might be there. I learned smudging, and how to clean a porcupine with my bare hands. Delia Bebonang, an extraordinary quilt maker from M’chigeeng First Nation was there, so when the porcupine arrived, I worked with her. She showed me and I just followed and that’s what we did all day until we got the quills off. That was an awesome summer.”

At her first teaching job as the art teacher at Joe Duquette High School in Saskatoon, Anna-Leah met another teacher/mentor, the late Bowser Poochay from Yellowquill First Nation. Bowser recognized that they “were the same people,” honouring the braided ethnicity of the Anishnaabe and the Saulteaux peoples, which warmed Anna-Leah’s heart. The late Bowser and Maggie, his partner, adopted Anna-Leah and her daughter Tanis into their family, and in time they were also adopted into the community of Yellowquill, where she and Tanis participated in seasonal ceremonies.

Also during her time at Joe Duquette, Anna-Leah became friends with the late Elder Laura Wasacase, who also became her mentor. “An Elder, I had seen her here and there, and she smiled at me and said ‘Good morning.’ I was a little bit shy because I knew she wanted to converse with me. We became friends. Laura and her sister were instrumental in the formation of FNUC. She was inspirational. And open. She made me look up and smile and feel significant in the world. It’s such a cold place in the world. I try to be that way with younger people, I try to connect.”

Anna-Leah’s parents and mentors guided her as she navigated her way to the career in Indigenous Education that she has followed. Her father broke the trail.

Cecil King wrote that he had encountered many barriers in his career but because of his efforts, Anna-Leah has not experienced those same barriers. She says, “With all of his diplomatic movement and conversations and connections and how he acted in diplomacy, he created good positive relationships, and he had the backing of Indigenous people who needed somebody like him to do negotiations at the institutions. I think that he made White people Indian friendly.”

Anna-Leah continues, “He had to tolerate a lot—people weren’t as open, especially back then. He had a lot of hard people to deal with, to change their minds, to get them to accept, to not be fearful of preserving our language and culture. I know that he had good relationships. At U of S they said, ‘Your father walks on water.’ What they meant was that his words were profound to them. He was an orator, and University was a place where his oratory was accepted and appreciated. He would sooner speak something than write it. He loved giving a good oratory and he would always start his speech with his grandfather’s prayer and end with ‘Mii maanda didabaajimowin’ (These are my words) spoken in the language.”

Carrying Their Legacies Forward for Future Generations

Cultural and language revitalization, participating in ceremony, and building relationships through community involvement and service outweigh the academic, paper-writing side of Anna-Leah. Her current research projects reflect her interest in cultural reclamation. She also has a passion for Indigenous visual art, which has inspired her to develop a master’s course in Indigenous art. Becoming an artist herself is an as-of-yet unexplored path. She has, however, collected some art teachers, having taken a course with Degen Lindner (daughter of Artist Ernest Lindner) and Mina Forsyth, another renowned artist, and Lois Simmie, a watercolour artist, as well as taking a portraiture class. Anna-Leah may yet explore this path in when she retires.

As a parent, Anna-Leah has adopted her parents’ model of parenting. Her father was influenced most by his Kohkwehns, whom, he says, “taught me to encounter the world with joy and wonder. She taught me so many things by letting me experience that world, in contrast to the way Mama taught” (p. 160). Anna-Leah says, “I think about my parents and the subtle way they taught me—not a direct pedantic approach, more the suggestion of things, so I would come to the right conclusion. My dad was a mentor and a teacher, but not necessarily in a spoken way. One principle I value is to be the model for the kids, and hope that they will pick that up. That’s important.”

In a letter to her daughter Tanis, included in her dissertation, Anna-Leah described her understanding of her role in shaping future generations: She wrote, “Ever since you were born, I realized my reason to be. I had one important job and that was to see to your well-being and I can say I did my best. I may not have always been perfect but I sure did my best. You are my anchor in bringing me back to my purpose which is to see that you are loved and know you are loved. I always put your needs before my own as my parents taught me. And so I write this letter to once again centre myself as I look forward with you in mind to the task at hand in thinking about our future generations.”

Returning once again to her father Cecil’s valedictorian speech, about the advantage of having Indigenous teachers, lawyers, doctors … and the need for leaders, Anna-Leah is also fulfilling her father’s youthful vision: She is a teacher, professor and leader and her daughter Tanis is also following in their footsteps, having benefited from the trail her grandfather blazed, and will complete her training as a physician on May 24, 2023.

Footsteps left by her ancestors, such as the Anishnaabe seven grandfather teachings of love, respect, bravery, truth, honesty, humility and wisdom, and the oral traditions, songs and stories passed on from her grandparents to her parents have also served to guide Anna-Leah as she seeks to live inter-relationally, in honouring the earth and its creatures and all those who have gone before her and those who will come after her.

Anna-Leah says, “We always have one foot in the past, as that defines who we are, and one in the present, moving forward to the future. Ekosi! Mii maanda didabaajimowin.”

Saskatchewan is experiencing a healthcare crisis, but this is not new for geographically isolated First Nations communities with limited access to healthcare services. In these communities, patients are evacuated to urban centres for treatment, traveling long distances, sometimes in inclement weather, to access primary and acute care services and diagnostics. Leaving their communities, they navigate the urban healthcare system, which is already running over capacity, while experiencing poor health, often compounded by language barriers. And, in Canada, Indigenous girls and women are disproportionately impacted by Indigenous-specific racism in the healthcare system. With these conditions in place, First Nation people living in these communities often delay healthcare until necessary. Indigenous people living in urban centres experience barriers to accessing healthcare, such as transportation issues (aggravated by the pandemic). Additionally, Indigenous people may experience distress due to institutionalized historical trauma and racism in the healthcare system. These factors contribute to the disproportionate poor health and well-being of Indigenous people in Saskatchewan.

Associate Professor Dr. JoLee Sasakamoose, an Anishnaabe (Ojibwe)/Quaker from Michigan and Ontario with membership in M’Chigeeng First Nation and active citizenship in Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation in Saskatchewan, and alumna Dr. Mamata Pandey (MA, PhD‘13), a research scientist for the Saskatchewan Health Authority with worldwide knowledge of healthcare services (and former postdoctoral fellow with JoLee), have worked together for over a decade to remove barriers and improve the health of Indigenous peoples in Saskatchewan. With the Cultural Responsiveness Framework created by Saskatchewan’s 74 First Nations communities, developed into a theory by JoLee, they use trauma-informed, strengths-based approaches to restore First Nations health and wellness systems. The researchers work with patient partners and healthcare providers, building relationships with First Nations and Métis communities to increase access to healthcare and provide culturally responsive interventions.

The Pandemic and a Shift in Focus to Maternal Care

Mamata and JoLee’s findings from an evaluation of the Indigenous Birth Support Worker (IBSW) Program, offered by the Jim Pattison Children’s Hospital Maternal Care Centre in Saskatoon, heightened their concerns about the experiences of Indigenous mothers in the healthcare system, causing a shift in their focus to maternal care. Their evaluation revealed that while the IBSWs were considered helpful, there is still need for better access to pre-and postnatal care and screening, better pain management, and more culturally safe and positive hospital experiences, including access to traditional teachings and spiritual care.

JoLee says, “It was hurtful to read how many birthing women were afraid to ask for pain management because they might be perceived as drug-seeking. If they did ask, they were perceived as drug-seeking. Often their pain was not being managed adequately especially when they were in fragile state of health.”

The need for access to the protective and healing nature of traditional teachings, spiritual care, and the support of an Elder during birth is reaffirmed by JoLee’s own birthing experience. Medicine man Eric Tootoosis and his wife Diane guided JoLee and her late husband from Poundmaker First Nation about restoring the birthing ceremony. JoLee recalls the importance of the teachings she received about maintaining a positive physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual environment because that had a direct impact on the growing baby. As a result, she gave up a research project to collect the stories of residential school survivors to protect her baby’s gestational environment and she was instructed to “walk away” if an argument developed between her and her late husband.

Still, there were gaps in her knowledge. During the pandemic, when cultural teachings were made accessible online, JoLee participated in a workshop on Ojibwe practices and teachings offered by a doula near her home community. JoLee says, “One of the teachings was about closing the birth ceremony. I hadn’t closed my birth ceremony. The doula told me how to close the ceremony and reminded me how forgiving our culture is, and it hit me as a deeply personal ceremony. Then, I thought, if that can happen 8 years after my son’s birth, why can’t we bring this to our community and support our women? That’s how organic it was. We wrote a grant proposal from there, and that’s how it all began.”

The researchers were awarded a grant from Jim Pattison Children’s Hospital Research Foundation. Their study focused on improving health outcomes by supporting mothers from pre-delivery to birth to post-delivery. But the shift towards increased social and physical isolation during the pandemic, prompted a decision to prioritize the well-being of mothers over data collection. JoLee explains, “Mamata and I took a massive step back away from the Mama Pod (maternal peer support group) to give them space, so they did not feel like they were being researched; the data wasn’t the most important part, providing support was.” Mamata adds, “Doing research for the sake of research is useless, and we might even hurt people.” The researchers stand by their decision despite being called on to defend it in their respective Western institutions. “This is a pilot study for us to learn what needs to scale up and be locally developed, which informs our subsequent study,” says, JoLee says. “We learned that it wasn’t a good fit for a program that comes from the heart to be in a Western institution even though it was held in the Lodge. We have too many bureaucracies in both institutions that prohibit us from being culturally responsive. That’s just the reality.”

Further, with traditional Indigenous birthing being a hot topic of interest, the research team stayed quiet about their grant. They didn’t want media attention which might disrupt the vital work. “It was like a gestation period, and we’ve been cautious with the program to ensure they have space and privacy,” says JoLee.

The Mama Pod

The Mama Pod was formed to “train Indigenous peers to advocate [for] and assist Indigenous mothers through pregnancy, labour, and delivery to postpartum stages” while providing a culturally responsive safe space to support the mothers. The mama peer supporters incorporated and modeled traditional Indigenous birth practices and worked to gain the trust of new mothers, sharing their own stories and creating space for the mothers to tell their stories and experiences with the healthcare system. The stories informed the researchers about the maternal needs of Indigenous mothers and helped them to facilitate the timely provision of and access to maternal care services. The researchers were looking to identify what kind of training the peer supporters needed. The team also created mother care bundles that provide resources for support services, and essential mother and baby items along with traditional medicines.

The Mamas

The researchers were gifted with three mama peer support workers: Jolene Taylor, a doula and full spectrum birth worker from Okanese First Nation; Brianna LaPlante, an Indigenous expressive artist from Fishing Lake First Nation who was also pregnant and an inspiration behind this study, and Kristen Tootoosis, a registered psychologist from Standing Buffalo Dakota Nation, and a graduate of our Educational Psychology master’s program.

JoLee says, “We had this trifecta of First Nation mothers with significant traditional background and experience.”

To find new and expecting mothers looking for support, Brianna and Jolene met with community organizations that serve Indigenous girls and women, such as the Rainbow Youth Centre. Several mothers decided to be part of the program, even though the pandemic presented further barriers and challenges. The support group met regularly in the Nanatawihowikamik Healing Lodge and Wellness Clinic in the Faculty of Education at the University of Regina.

“A Beautiful Journey”

Over time, the mama peer supporters built trust, and the participants opened up and talked about their challenges and anxieties, though the journey was difficult. Jolene says, “We were doing the groundwork with the mothers, hearing their experiences, and facilitating the groups. Much of it was storytelling, and holding space for the moms cause they needed that space to be heard. It was really difficult to let them know that their story was safe with us, and many held back things when we went more in-depth, [for example, asking] how their personal experience was in the hospital and how they were treated outside the hospital.” Many new mothers had normalized the mistreatment they had experienced, so part of the work was building awareness. As well, many new moms from an urban setting also lacked a connection to the community and were “in survival mode,” says Jolene, “That’s why the work was so beautiful: We made a community for them. We did gain their trust in the end, and for the new moms that stuck with us for the last year and a half, it’s been a beautiful journey,” says Jolene.

Mamata adds, “I think an exciting and very wonderful thing happened due to the interactions between the team facilitating those groups and the mothers seeking support. The facilitators were able to see the scope and impact of their work in real life and that motivated them to then take advanced education while some of the mothers themselves wanted to become doulas to support others. I think it was very inspirational. It was a beautiful thing that emerged.”

This result motivated the researchers to look into various training for the peer supporters, finding opportunities for women to move ahead or take on a support role if they wish to. Thus, in the fall of 2022, Jolene was sent for Indigenous Lactation Consultant Training in Billings, Montana.

Mama Jolene Taylor’s Story

Jolene is a 25-year-old mother of five children, two of whom she gave birth to. When her daughter was born in 2017, Jolene dramatically switched her career plans, even though she was only one class away from achieving her Indigenous Communication Arts diploma from the First Nations University of Canada.

Jolene says, “My outlook on life changed for the better. I had this passion within me after my daughter’s birth. I wanted to be a support person with moms and become a midwife eventually; that’s my long-term goal.” Coming from a long line of midwives, Jolene refers to her career shift as “activating blood memory.” She explains, “I was taught that as Indigenous people, our ancestral blood memory is in our veins. … The DNA of our ancestors courses through our veins. Everything is passed on to us through the blood, and that is what it means to be a Nehiyaw person, to be a Cree person: We are born with the knowledge, the culture, and the languages, and it’s up to the parents to take on the responsibility of child-rearing, to reactivate the blood memory. Everything starts at conception. Everything. If you want to immerse your children in language, then be around people who speak the language, and go out and learn your language, a lot of that blood memory could be reactivated just by sitting in sacred spaces. I come from a matriarchal line of Indigenous midwives on my mom’s side.”

Jolene tells her mom’s oral traditions of growing up while settlers were coming to the West: “They were bringing their pregnant wives, and my great, great grandmother helped these families birth at home. They were creating their homesteads, yes; they were settling in the West, and yes, it was a scary time. But my kunshi helped these babies be born in a healthy way, even though there was a language barrier in the early 1900s. My kunshi shared her medicines and teachings with these settlers, and those are the gifts, and that’s what empowers me to carry on with this work to revitalize those things ’cause our medicines saved the non-Indigenous people; they wouldn’t have survived if it wasn’t for living amongst us. It’s that blood memory that I love to reactivate by being in these trainings by being in Indigenous spaces that I feel safe in.”

Cultural Revitalization in Birthing Practices

Jolene is revitalizing culture one birth at a time. She says, “That’s exactly what my role is as a doula, as a birth worker, as an auntie, to support first-time moms: It’s the revitalization and restoration of culture and teachings and protocols that come with being a First Nation woman. A lot of these ceremonies are very unique to each tribe. We are not all the same. We can’t just pan-Indigenize teachings and [call them] Indigenous protocols. We have five First Nations in Saskatchewan: the Cree, Dakota, Nakota, Lakota, the Saulteaux people, and the Métis people have their own teachings and protocols that they established over the years, too.”

Jolene was raised with, and is practicing, Cree/Nehiyaw culture and protocols around birth. “I always say, ‘I’m a privileged Indigenous woman’ because I can access cultural traditions and protocols. I realize that many people my age don’t have that. A lot of my work is just to revitalize and restore practices.”

Placenta Burial is One Such Practice. Both JoLee and Jolene buried the placentas of their babies. Jolene, however, did not know that taking the placenta home from the hospital was even an option for her first birth. It was upsetting for her when she first learned, through the non-Indigenous doula training she took, what happens to the placenta in the hospital:

“I asked the question, if you don’t take your placenta home, what do they do with it? They explained, ‘It gets incinerated, it’s another organ that gets incinerated.’ That made me burst into tears. I was the only Indigenous woman in this training, and I started to cry and I said, that was a part of me that I built, that was what kept my baby safe, and to find out that all they did was burn it. I knew that my blood memory triggered that reaction.” So, Jolene investigated the matter back at home, asking questions about what they used to do when women were giving birth in tipis.

“The question activated the blood memory of my kôkom,” says Jolene, “and she remembered the births that happened on the reserve and what they did. Just from asking one question, I was able to have a lot of knowledge shared with me, of how it was done back in the day. That was one thing that opened my eyes to [the benefit] of spending time with elders, spending time with people, asking those questions, that’s the revitalization part that I love to be in.”

Restoring Breastfeeding Practices. Breastfeeding is another practice Jolene is passionate about revitalizing. She happily signed on for Lactation Consultant Training when the opportunity arose. Jolene says, “I have such a passion for breastfeeding. I’m a full-spectrum birth worker, so that’s everything from when a girl first gets her moon time, her menstrual period, and menopause. That is the full spectrum. The space I love to be in is birthing, breastfeeding, and postpartum. To normalize breastfeeding has always been a passion.”

Jolene could talk for a long time about the benefits of breastfeeding, and she enjoys sharing her own positive breastfeeding story with other new moms who may need convincing that moms their age can breastfeed. She says, “Many new moms haven’t seen a breastfeeding mom. Their mothers didn’t breastfeed them, and my mom didn’t breastfeed me. It’s been a long-lost tradition because of colonialism, displacement of our families, and especially today with the high apprehension of babies.”

“I loved attending the Indigenous Lactation Consultant Training because I want to normalize breastfeeding. The first milk, the colostrum, it’s the first sacred food for Indigenous moms to give their babies. It’s been the first food of babies since time immemorial. It’s not foreign; it’s a natural thing to do,” says Jolene.

The Helper, not the Conductor. Jolene makes the important distinction that in her work as an Indigenous doula, she views herself differently than the non-Indigenous doulas: “What I was taught in the doula training was to be very hands-on and to be at the forefront, but for me, it is about stepping back and helping to create the space around the parents who are giving birth and to protect them. I’m the oskâpêwis, the ceremony helper; I’m not the conductor,” says Jolene.

Pride in Indigenous Identity

Residential schools have played a significant role in the dissolution of family and cultural ceremonies and traditions. But that isn’t the whole story, as Jolene points out: “Yes, we are born with trauma, but we are born with other beautiful things, and we don’t have to focus on the negative. We are born with culture, born with identity; we have things specific just for us.”

The Indigenous Lactation Consultant Training instilled in Jolene a sense of pride in her identity: “I walked away knowing, being empowered, of being prideful of being Indigenous, of being First Nation, being born First Nation.”

Science Catching Up With Indigenous Knowledge

Indigenous practices around birth are muskiki (Cree medicine) that Western science is only beginning to understand. For example, JoLee tells a story about the wâspison (Cree baby swing) they used for her son when he was born: “My kôkom asked what I would be using for our baby to sleep in. I said, ‘My husband built the wâspison over our bed with two ropes and a blanket.’ That swing sure wouldn’t have passed any SHA safety standards. My kôkom said, ‘O my girl, your baby will never have ear infections; that swing will keep your baby’s inner ear fluid balanced.’ Our medicine and ways of knowing have medicines, natural protective mechanisms, in them in ways that may never be understood.”

For over a year, JoLee has been studying with Gabor Maté, a renowned expert in addictions and trauma, and she has learned, “the science is clear: what occurs in the nervous system during pregnancy imprints the child,” says JoLee. As mentioned, JoLee’s medicine man had instructed her 11 years ago to keep her baby’s environment stress-free.

Maternal Care Key to Positive Health Outcomes For Future Generations

JoLee says, “Although the Harvard Center for the Developing Child has validated the importance of the environment for babies in utero and the role of adverse childhood experiences (ACES) for the past 25 years, it is still not widely recognized or practised in mainstream society. This underscores the need for increased education and awareness regarding the effects of stress on fetal and child development. Our team views maternal care as the key to reversing health outcomes. Supporting moms will have impacts for generations to come.”

Bringing Indigenous Lactation Consultant Training to Saskatchewan

JoLee and Mamata hope other Indigenous moms will be trained as lactation consultants. JoLee says, “We want to bring the training here and put it in the communities or have an Indigenous-specific urban one. Jolene can help inform what we bring here. … Whatever we bring here will be adapted because we’re different here: The urban must look different, and the Métis one must be different.”

Indigenous support, improved access to Western health services, and the revitalization and restoration of cultural birthing practices protect mothers and babies from preventable health conditions and promote wellness. This work is vital to reversing historical trauma and poor health outcomes for future generations. As Jolene said, “everything starts at conception,” so cultural protections, access, and supports must also be put in place before birth.

Congratulations to Education student Ace Casimiro on being awarded one of three University of Regina Retirees Legacy Scholarships! The $8000 award goes to three University of Regina students going into their final year whose “potential for doing graduate work has come to the attention of faculty members.”

Dr. j wallace skelton, who nominated Ace for the award, wrote, “Ace’s final project was a series of detailed on-line learning modules for teachers of English Language Learners to support them in becoming more inclusive of 2SLGBTQA+ students. It was interactive, rigorous, detailed, engaging, thorough. The sheer volume of research Ace had done to put this together was well above my expectations for a 3rd-year class. It’s classic Ace that his response to the assignment was to see an actual need in the world (a lack of 2SLGBTQA+ resources specific to ELL classrooms) and to then work to create professional quality resources to meet that need. It was clear that he had a deep understanding both for the topic and ways to motivate teachers to change their practice. In education, we encourage students to employ a social justice lens a teach for justice. It’s clear that that infuses Ace’s work and thinking.”

This is only the second time the award has gone to an Education student!

An ARTS EDUCATION degree can OPEN DOORS to opportunities beyond being a teacher in the school system as today’s spotlight demonstrates.

We’re shining light on arts education alum Dillon Lewchuk (MA, BA, BEd, RCAT, RCC, CCC) who currently has three professional roles: He is a full-time clinical counsellor working at Homewood Ravensview with a dynamic interdisciplinary team of psychiatrists, addiction physicians, nurses, and a large range of therapists to treat mood and anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, and addictions. He is also an art therapist in a private practice, providing virtual art therapy and counselling services to children, teens and adults. And he picks up contracts to teach postsecondary classes for art therapy colleges, to advise on academic theses, and to train mental health professionals about 2SLGBTQIA+ therapeutic care.

SUCCESS. CONFIDENCE. PROFESSIONAL SKILLS.

Our arts education program equipped Dillon for these professional roles by giving him confidence and essential skills for success:

“I learned how to understand learning styles to present information that is accessible and I gained the confidence to present in order to help those I support, like when I give lectures and training to develop the competencies of other professionals, run group therapies, or provide psychoeducation to clients struggling with their mental health.”

The arts education program helped Dillon to “create and deliver educational content and training that helps support individuals belonging to vulnerable and marginalized communities,” as well as helping to foster his passion to continue learning and to “further cultivate my helper side by completing my Master’s in Art Therapy.”

Through his arts education program, Dillon strengthened his intuition “to trust his creativity and think outside the box to fill the gaps in society.” Dillon says, “I have been able to start community initiatives for adults with intellectual disabilities, connect diverse communities together to work towards reducing stigma, and construct/revamp programs for non-profit organizations.”

CONNECTIONS.

Like many alumni, Dillon appreciates the deep connections he made through the arts education program: “I created life-long friendships with my peers, as well as meaningful, professional relationships with my professors who supported me, and continue to support me beyond my undergrad program.” Dillon believes that this learning community strengthened his confidence that he could excel in any area he chose after graduation.

Dillon also enjoyed the “variety and vastness” of the program, with its opportunities for “multiple internship experiences, the holistic range of academic classes (literacy, music, dance, drama and visual art) and the small cohort of like-minded individuals.”