Following in his mother’s footsteps, a teacher before she married back in a time when women had to give up their profession if they married, Nick Forsberg knew he wanted to become a teacher. He still remembers the anticipation he felt when he opened his acceptance letter. While an Education student, he worked hard, fast tracking his program while playing volleyball with the Cougars, and even socializing enough to enjoy the life of a university student. After a very full 3½ years, in 1984, Nick graduated with his B.Ed. He then had the privilege of going back to his hometown of Chaplin, Saskatchewan to teach alongside his former teachers.

Following in his mother’s footsteps, a teacher before she married back in a time when women had to give up their profession if they married, Nick Forsberg knew he wanted to become a teacher. He still remembers the anticipation he felt when he opened his acceptance letter. While an Education student, he worked hard, fast tracking his program while playing volleyball with the Cougars, and even socializing enough to enjoy the life of a university student. After a very full 3½ years, in 1984, Nick graduated with his B.Ed. He then had the privilege of going back to his hometown of Chaplin, Saskatchewan to teach alongside his former teachers.

Before long, Nick began his master’s degree at Northern Illinois University (NIU). Dr. Larry Lang had encouraged Nick to follow in his own steps, to take his master’s in outdoor teacher education from NIU. Further, Nick says, “The people I was reading about in outdoor education during my undergraduate years were on faculty at this university.” After finishing his Master’s in 1987, Nick moved back to Regina to teach at Dieppe Elementary School and he also taught the Winter Outdoor Course as a sessional at the U of R. In 1988, Nick was offered a full-time term appointment, which eventually transitioned to a tenure-track position. This was the beginning of a 32-year career with the Faculty of Education. As a requirement of his employment, Nick began his PhD in 1992 with the University of Alberta, and took 1 year off from teaching at the U of R to do his residency in Edmonton and successfully defended his dissertation in 1995.

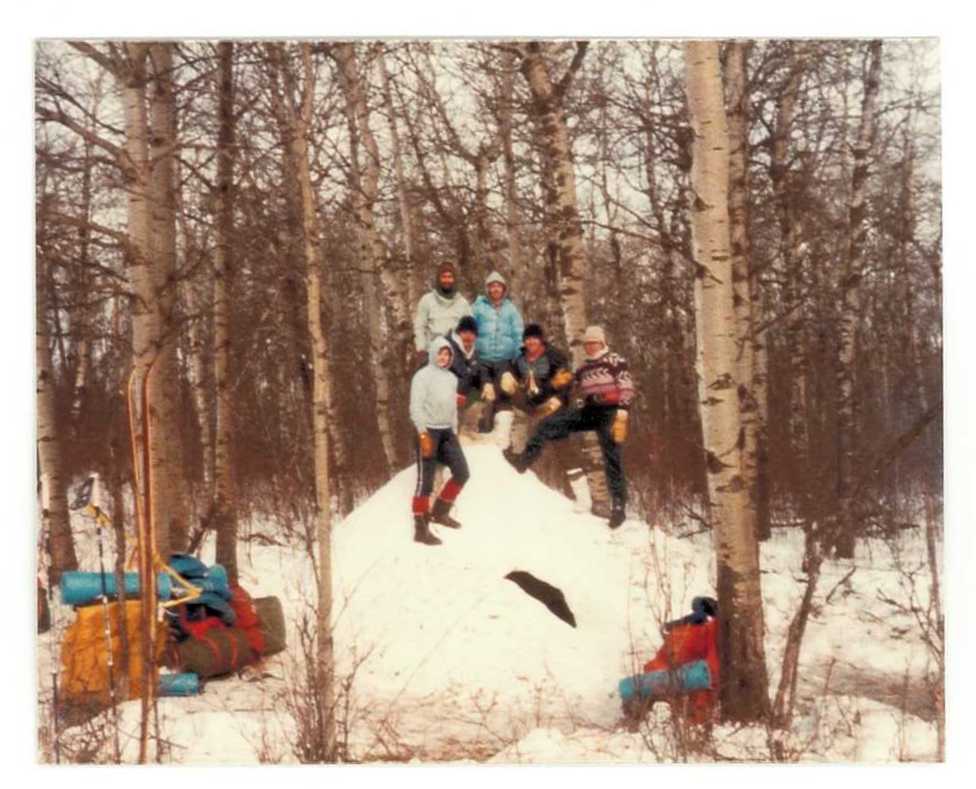

Nick points to his undergraduate and faculty experiences at OCRE (Off Campus Residential Experience) held at Fort San, Saskatchewan for many years, as the opportunity that changed the course of his career. “Everybody went, 120 students and the current faculty, 3 days in fall and 3 days in winter.” OCRE was so influential that it became the topic of Nick’s dissertation. The reason OCRE was significant was “because we did it, we didn’t just talk about it,” says Nick, “The experience modeled that relational quality in teaching where teaching and learning become real…Professors and students teaching and learning in the outdoors, eating together, and, if they wanted, sleeping in a tent or teepee in fall or a quinzhee in winter—the outdoors leveled the playing field—We were all just people.”

An insight Nick gleaned from the OCRE experience was that “teaching and learning are not confined to a four-walled building or classroom.” He refers to the late Dr. Garth Pickard’s regular question about exit and enter signs above doors in buildings, asking, “When we leave the building are we exiting or entering a way of teaching and learning? Maybe these signs should be reversed: exit signs on the outside and enter signs on the inside.”

Nick has vivid memories of colleagues teaching their subject matter outdoors, often through an interdisciplinary lens. Reminiscing about the days before budget cuts took OCRE and its later version PLACE (Professional Learning as Community Experience) out of the program, Nick points out that being out on the land at OCRE was a natural way of teaching and learning content. “We also learned alongside our colleagues from SIFC (now FNUC) and SUNTEP as well as the Bac program. Being on the land created an embodied living curriculum and we engaged in this experientially.”

Some major influences who encouraged Nick’s path in health, outdoor and physical education (HOPE) include Dr. Larry Lang, Dr. Garth Pickard, Dr. LeOra Cordis, Dr. Meredith Cherland, and Dr. Ray Petracek. Nick says, “The embodiment of what I experienced as an undergrad drew me to work at the U of R because of the respect I had for the professors who taught me. The relational quality they modelled, I wanted to emulate in the Faculty.”

Nick continues, “The privilege of teaching alongside my former professors was very gratifying. They invested their time in me, so I felt a responsibility to pass that forward to my students, and to get in the trenches and teach.” But, beyond their encouragement, Nick says, “I always felt that I could have a greater impact by teaching future teachers. I wanted to help shape the field of education and to create a voice for health, outdoor and physical education and the vital role it plays in the lives of children and youth.”

To further his influence, in 2003, Nick took on the Associate Dean of Undergraduate Programs role: “Working with undergrad programs—that was my passion—finding ways to meet with faculty in groups and talk about programs and the ways to deliver the best program.”

Over the years, Nick also chaired the HOPE subject area and sat on various committees and external boards, at one point serving as president of the Canadian Association for Health, Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance (CAHPERD–now PHE Canada). It was meaningful, to “find a network of colleagues with a similar passion for human movement and the critical importance of the outdoors, and to have the opportunity to sit around tables and influence changes provincially and nationally,” says Nick.

Nick fondly recalls his summer outdoor education class that he taught every 2 to 3 years, where he took students for a 3-week trip on the Churchill River in northern Saskatchewan. Part of the experience was a “solo,” where students were dropped off on an island by themselves for 25 -30 hours. “It was an opportunity to be by yourself without technology. We believed that this experience allowed students to take time for inward reflection. Students were always saying, ‘Don’t take solo out of the course. It’s the best thing I could have done.’ For some, the experience was like an epiphany.” says Nick.

Quoting Nel Noddings, “We live storied lives and we tell stories about our lives,” in answer to the question of what advice he offers colleagues, Nick says: “Invest in what it means to be a pedagogue, know the stories about teaching and embody those stories. Know the story of the teacher education program of the Faculty of Education. We have a responsibility to the voices that came before us. Never lose sight about why you are here and continue the story.”

In answer to the question of what is significant about the work done in the Faculty of Education, Nick says, “The responsibility of our work may seem simple but it is complex because we work with people. It’s a huge responsibility to help prepare and support (be)coming teachers who will influence children for 12 years of their lives. This work requires humility, and we need to walk alongside these future teachers and experience what they experience. It’s living that story: ‘I need to be in the quinzhee, not just talk about it.’”

As he retires, Nick has no intention of taking a break from teaching: “I plan to engage in leadership development but I want to do this experientially and through the outdoors. I believe this truly allows us to ‘see’ the human side in all of us and for who we are.” He’s moving to his classroom of choice, the great outdoors, allowing nature to do its work. “But more importantly,” says Nick, “I’m looking forward to more time with my family who unselfishly gave their time for me to pursue my passion for the past 32 years, mixed in with time for some paddling and golf!”

Follow us on social media