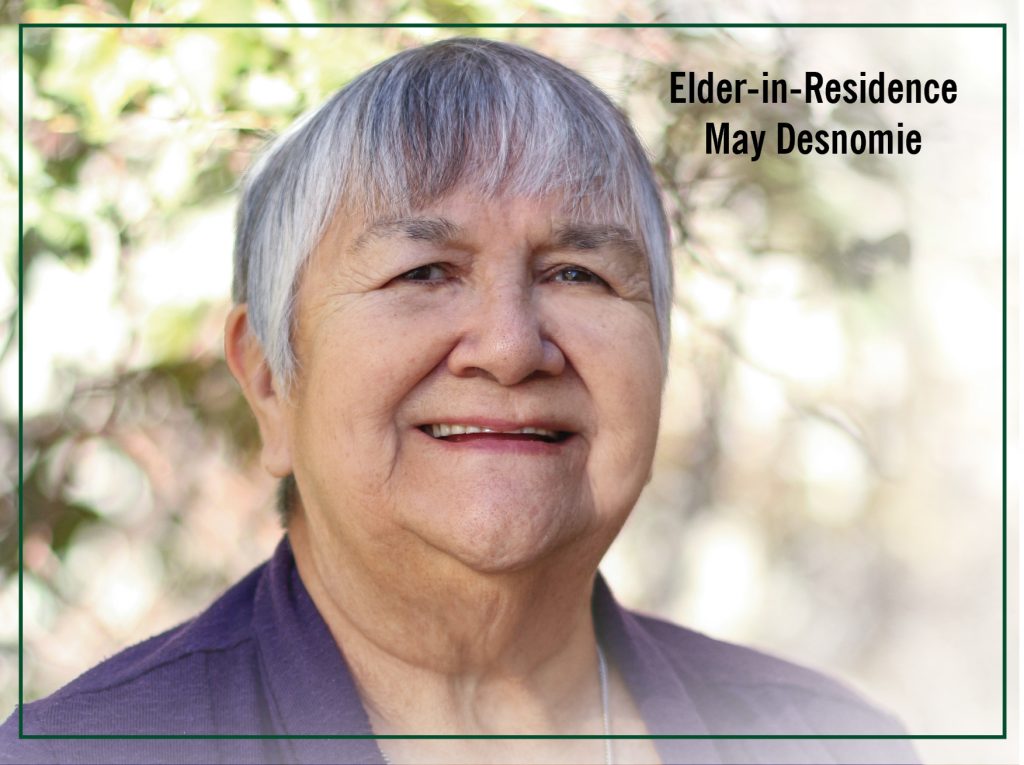

Elder May Desnomie, a Woodland Cree from Peter Ballantyne First Nation, was born and raised in the northern Saskatchewan hamlet of Sandy Bay. Her family on both of her mom’s and dad’s sides and grandparents going back generations lived off the land, hunting, trapping, fishing and gathering. Before she was taken to the Catholic-run Guy Hill Indian Residential School in The Pas, Manitoba at the young age of 6, May also lived off the land: “I was 100% immersed in my language and culture until I was taken away to residential school in 1956.”

If being far away from home at such a young age wasn’t enough hardship, residential school was made harder because of the parental visitation policies: “Parents weren’t allowed to visit in residential school. They had a room they called a parlor next to the principal’s office. The parents would come to visit there, and they were only allowed one hour,” says May.

Though attending residential school didn’t destroy May’s Catholic faith, it did affect the faith of some members of her family. “There are four of us that went to residential schools and two will not have anything to do with the church. I personally didn’t suffer any physical or sexual abuse.”

Still, May recognizes the damage done by the policies of residential schools, She says, “I have nothing good to say about residential schools. They destroyed our cultures, our languages, our families. For myself, I met many good people along my journey. Although I am not going to say anything nice about residential schools, I will say there were nice people. However, the policies were destructive: the residential school was trying to destroy our way of life. That is still their goal: They still want to assimilate us, to fit us into the Canadian multicultural dream, but they can’t forget that we were the first people on this land.”

May moved to Wilcox to attend high school at Athol Murray College of Notre Dame boarding school after 9 years as a student at Guy Hill. She says, “I was sent there as part of the integration policy. My aunt was a teacher/nun at the elementary school there, and I could see her because she was a supervisor.” The change in landscape from her northern roots was a big change for May, “It was a culture shock for me, being from northern Saskatchewan with the rocks and the forest. Honestly, Wilcox has the flattest land in Saskatchewan, I swear. And we didn’t have the water that we had up north. When I was a child, you could drink water right from the lakes up north. We drank the water from the dugout at Wilcox and it was bad.”

After being in an institution for 11 years of her life, May decided to move to Saskatoon to take her Grade 12 from E. D. Feehan Catholic High School. “I had to find some freedom. I don’t know why, but I ended up in Saskatoon. Indian Affairs put us in boarding homes.”

May decided to become a teacher after graduating high school because she wanted to help change the narrative of Indigenous people in Canadian society. She says, “When I was in residential school, I did not learn my Indigenous history, like the history of Indian people. We were told we were savages and pagans and I didn’t think that was right. I was hoping I could change that narrative in the classroom to some degree.” After graduating from the University of Saskatchewan with a Bachelor of Education, May and her husband Gerry Desnomie returned to the North, moving to Red Earth First Nation where she taught Grade 1 students.

Changing the narrative has been the work of May’s entire career in education: “It’s coming along slowly, but now they teach treaties in the classroom, and now they have native studies in high school, but they still need to change the curriculum to have more of the Indigenous perspective in there.” To help with curriculum change, May is sitting with an elder’s group that is advising the provincial government on curriculum.

May also has a heart for reparation work. She belongs to three groups dedicated to this work: the Intercultural Grandmothers Uniting (IGU), which is made up of Indigenous and non-Indigenous women working toward building bridges of understanding, respect, trust and friendship; the Aboriginal Non Aboriginal Relations Community (ANARC); and a TRC committee, with the Catholic Church. “They are hoping to repair the wrongs done by the church to Indigenous people, so that is why I joined that group.”

In her role as Elder-in-Residence with the Faculty of Education, May hopes to continue her work of changing the narrative about Indigenous people. She says, “I hope I can tell the wider society about Indigenous people, that we are part of society and we feel the way they do: We have our joys and our sorrows, our hopes and our dreams. I want them to know about our history, our Indigenous history. Many of them wonder about and have so many stereotypes about Indigenous people, that ‘they’re lazy, they don’t want to work, or they are alcoholics,’ and those are the ones you see. The majority of us are okay, we are successful. This is what I want to tell the general public. The government has made us invisible in the past, through residential schools and restricting us from leaving our reserves, and they told the wrong story about us.”

Being made invisible damages Indigenous people; May says, “They don’t know the damage they are doing to our person; it makes it so you’re not proud of yourself as an Indigenous person. I always tell my students to be proud of who you are; I know you can’t be successful until you are proud of who you are. Otherwise you are always trying to hide who you are.”

“I want to tell the right story. But not just me, I will have a hard time trying to educate society. Canadians will have to go out and educate themselves, read books, and find about our history and they will know who we are and can be our allies, and help us move forward and walk with us.”

Elder May Desnomie replaces the former Elder-in-Residence, Elder Alma Poitras, who retired recently.

Follow us on social media