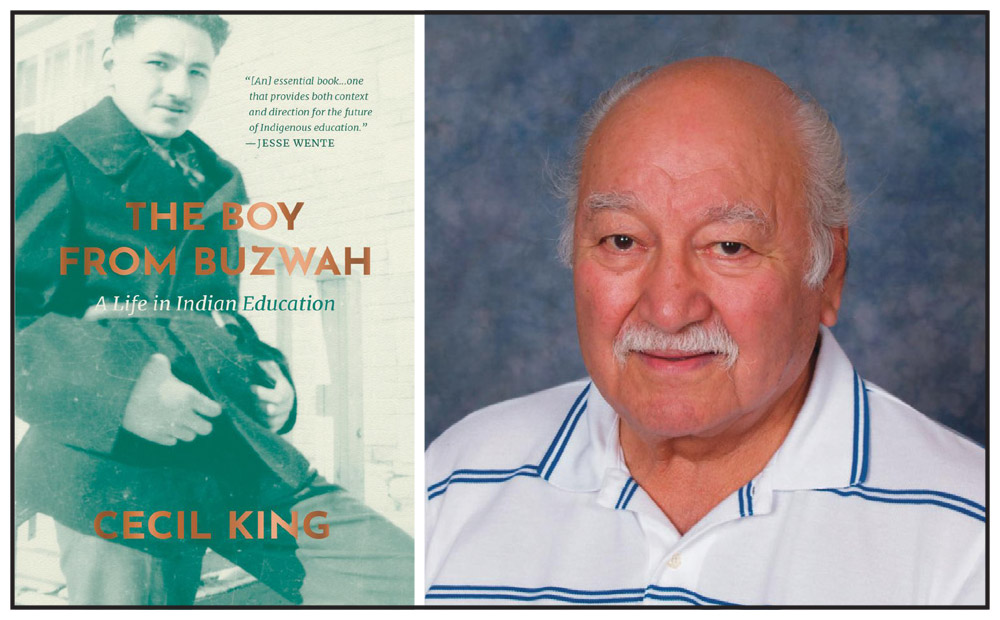

The footsteps of ancestors, family, and mentors have guided Dr. Anna-Leah King in her life-journey. Anna-Leah is Anishnaabe, an Odawa on her father’s side, the late Dr. Cecil King, and a Pottawatomii on her mother’s side, the late Virginia (Pitawanakwat) King. The name stories behind these nations are outlined in Anna-Leah’s father’s recent memoir, The Boy From Buzwah: A Life in Indian Education: Cecil wrote, “My grandfather maintained that in the beginning, there were three biological brothers—Odawa, Pottawatomii, and Ojibwe. Over the years, they went their separate ways, and as a result, three separate nations were formed—the Ojibwek, the Odawak, and the Potawatamiik,” called the “Confederacy of Three Fires—the Anishnaabeg,” a word which means, “I am a person of good intent or I am a person of worth” (pp. 1–3). These stories form the core of Anna-Leah’s identity.

Like her parents, Anna-Leah spent her early years on Manitoulin Island (Island of the Great Spirit) in Northern Ontario, surrounded by family, culture, Ojibwe language, and history. Her early experiences have lingered and wafted throughout her journey, like campfire smoke in a sand plain forest, imprinting her worldview.

Anna-Leah’s father was a major influence in her life. He blazed the trail for many of the professional choices she has made. Even though teachers are part of her blood line—her great grandmother and father were teachers—Anna-Leah didn’t like school, and didn’t see herself becoming a teacher: “I never saw myself as a teacher. When I was in my younger grades I swore to God I would never be a teacher. I found schools unwelcoming places, aesthetically dead places, with ugly muddy green and orange paint,” says Anna-Leah.

Aesthetics aside, Anna-Leah’s early experiences with some teachers were not positive either. She recalls a confusing and frightening experience in kindergarten, when she held out her hand for a reward and was instead strapped with a leather strap by her teacher.

Despite her dislike of school, Anna-Leah’s father encouraged her to become a teacher. And once, when he returned from one of his many trips, he brought Anna-Leah a miniature brief case. “It was just like his. That was the first seed planted, that when I grew up, I could be like my dad,” she recalls.

In 1969, when Anna-Leah was 6, her Dad took a job in Ottawa, where Anna-Leah spent the remaining years of her childhood. But in 1971, when her father moved two provinces west, to Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Anna-Leah determined she would follow in his footsteps: “I couldn’t wait to reunite with my dad some way, somehow.”

For her final year of high school, she (along with her sister Alanis) moved to Saskatoon to be with her father. Following high school, Anna-Leah decided to become a teacher and finished her teaching certificate in 1989 through the Indian Teachers Education Program (ITEP) at the University of Saskatchewan, where her father had been the founding director. Despite her early objections, she had become a teacher, like her dad. But the trail didn’t stop there.

Cecil was an Indigenous educator for more than 60 years. He had a tremendous impact on Indigenous education in Saskatchewan and impacted the lives of the many students he taught. His career took him from teacher, to principal, to professor, and into multiple leadership roles provincially and across Canada, mostly within the university context.

Cecil King’s Legacy: An Era of Indian Control of Indian Education

During the 60s, the political and social environment was developing into a storm following the adoption of a forced integration/assimilation policy, which threatened the continuation of Indigenous languages and culture. In his memoir, Cecil (2022) wrote, the Federal Government’s “Department of Indian Affairs was busy transferring education to local school boards…negotiating joint school agreements without the approval of individual First Nations” (p. 209). This colonizing policy resulted in more standardized and irrelevant curriculum and content in Indigenous schools that devalued and disregarded Indigenous worldviews and local Indigenous involvement. Cecil regarded the policy as responsible for the problem of, “Indian children achiev[ing] only limited education characterized by low education achievement rates, high failure rates, so called age-grade retardation and early school leaving” (p. 222). He maintained that pride in one’s identity was critical to success in life and education.

Cecil grew up in a bilingual, bicultural, multigenerational home where English was the only language spoken. His grandparents who raised him had been convinced by their Catholic schooling that English was the only path to success, and should be the language spoken at home. He had a well-rounded education at home: His grandmother who had been trained as a Victorian-era teacher, was a strict disciplinarian; his grandfather was a talented handyman, who taught Cecil how to do things but also transferred the Odawa history and worldview to Cecil; and Kohkwehns was his emotional support, who, Cecil says, “listened to me and taught me how to be a ‘good’ Odawa” (p. 323).

From Grades 1 to 8, Cecil was taught by First Nation teachers at the Buzwah Indian Day school and he learned to speak Ojibwe at school from his peers. He excelled at his studies: “At school we learned and communicated in English, and although what we read was foreign to us, we learned. … We didn’t read about First Nations history or heroes, but we lived among First Nations people and learned that part of our education from them” (p. 51).

When he had finished Grade 8, Cecil had to leave his home and community to attend a residential high school, St. Charles Garnier Residential School in Spanish, Ontario. Cecil, along with three of his peers, passed the entrance exams, and bid goodbye to their families and friends. Ominous black buses arrived each year to take the children to residential school. Cecil had mixed emotions about going, because he was leaving behind his family (and beloved Kohkwehns) and community and because he knew from experience that sometimes kids didn’t return home from residential school, but he was also excited and proud to be continuing his education.

At Garnier, he again excelled in his studies, despite being told that Indigenous culture was “quaint” and that students should not expect to rise to the pious level of the French Jesuits who taught them. Students developed a subculture where Cecil continued to learn and practice Ojibwe, and where they traded off items from their assigned work areas. “Recalling these things, I realize that this was our world. We created a culture within the institution’s culture. We found a way to circumvent the forces that dominated,” (p. 131) wrote Cecil. Cecil was valedictorian when he graduated in 1953.

After high school, Cecil took a 6-week course in order to take a teaching position at West Bay School on Manitoulin Island. The post-war baby boom was creating a demand for teachers. In 1954, Cecil married Virginia, whom he had met at residential school. He also took a second 6-week course and took another teaching position at Northwest Bay. At this stage in his career, he already had a drive to take on a principal role. The following year, he enrolled at North Bay Teachers’ College and became a qualified teacher by 1957, after which he was hired as a principal at Dokis Bay Indian Day School.

Cecil worked throughout his career to take back control of Indian education. He described this work as complex, involving the development of curriculum, teaching materials, lessons, and workbooks for teaching Ojibwe. Ojibwe teachers needed to agree on how the language would be written. Cecil wrote, “It became apparent that standardizing the written Ojibwe language was a necessary step in establishing a province-wide Ojibwe language teaching program. Here we ran into the debate over the appropriate orthography. Now we realized that to teach the language in the school we needed to have written language and material for the children to read. … Success in teaching Native languages in schools would be dependent on a teacher-training program specifically for teachers of Indian languages” (p. 182).

Working together with his cousin Mary Lou Fox-Radulovich, the two were successful at getting an Ojibwe language program approved for teaching in elementary schools. Trent University began offering a Teaching Ojibwe in Schools course that Cecil taught in 1970, delivering the course to non-Indigenous students.

There he met Dr. Art Blue who encouraged Cecil to enter full-time study at the University of Saskatchewan through the Indian and Northern Education Program (INEP). The decision was pivotal: “When I made the decision to go to Saskatchewan, I did not know that it was going to have a profound impact on my life” (p. 202).

The 1973 adoption of the National Indian Brotherhood policy statement on Indian control of Indian education, “sounded the death knell for the policy of forced integration policy and led to the establishment of on-reserve schools,” (Cuthand, 2013). At the same time, Cecil’s career was taking a dramatic turn—in his words, he was “joining the revolution” (p. 201). Little did he know that Rodney Soonias of Red Pheasant First Nation, who was the director of the Saskatchewan Indian Cultural College (SICC), had selected Cecil to be the founding director of the ITEP: “The new task was to design, develop and implement a program that produced Indian teachers who received the same credentials as other Saskatchewan teachers but who were equipped to change the education of Indian children in the province in accord with the wishes of the chiefs, communities, and parents while preparing children for their place in society” (p. 209). His decision to stay in Saskatchewan and take on this role came at a great personal cost: the permanent separation between him and Virginia. By that time, they had five children.

As director, he travelled to various Cree communities in Saskatchewan to establish pilot Cree language projects. Others were also establishing Indigenous language programs. Cecil wrote, “Everyone …was on side and working towards the same goal: to take control of education for First Nations people in Saskatchewan. The power, the force, the energy that was released was incredible” (p. 224).

After finishing his B.Ed. (’73) and M.Ed. (’75), Cecil began his PhD journey at the University of Calgary. In 1983, he was the first Indigenous Canadian to receive his PhD from the University of Calgary. During the 1980s, he was head of the Indian and Northern Education Program, which positioned him as a faculty member in the College of Education at the University of Saskatchewan. Cecil served on multiple dissertation committees at multiple universities including the University of Regina. After the program he headed was folded into the Foundations department and Cecil was denied promotion, he left the University of Saskatchewan and took a full professorship at Queen’s University where he became the founding director of the Aboriginal Education Program.

Looking back to Cecil’s 1953 valedictorian speech, the seeds of the vision that would characterize his career can be seen: Cecil said, “We all realize how advantageous it would be to have our own teachers, lawyers, doctors and politicians, men and women who will work hand in hand with those who now are working for our rights and prosperity. We need men and women who will be exemplary leaders in our own communities …men and women of vision, initiative and energy” (p. 138). Cecil himself became that exemplary leader, and a man of vision, initiative and energy. He cleared the trail for many who would also follow in his footsteps.

When Cecil passed away May 4, 2022, Doug Cuthand eloquently wrote, “At 90 years of age, the final school bell rang and he began his journey to the next world. King may have moved on, but his work lives on in the hundreds of teachers whose lives he touched”.

Dr. Michael Tymchak, former dean in the Faculty of Education at the University of Regina, and former director of the Northern Teacher Education Program (NORTEP) in La Ronge, says, “Cecil was a leader in Indigenous Education here in Saskatchewan, and across Canada. As Director of ITEP he broke trail for many other First Nation educators to follow. Cecil understood the corrosive impact of colonialism but his life spoke most eloquently to vision-casting and the creation of educational opportunities for First Nation students. He was a believer in self-determination and an advocate for the vital importance of preserving Indigenous languages and culture. Strong in his own Anishnaabe identity, he was unafraid of strategic ‘co-determination.’ Cecil knew that Indigenous peoples and their culture(s) had much to offer the larger society and he dedicated his life to manifesting this conviction.”

Dr. Tymchak continues, saying, “Cecil provided a role model for others to follow and was unfailingly supportive of the establishment of other Indigenous teacher education programs. During my years at NORTEP, Cecil offered enthusiastic encouragement, came up to La Ronge to teach courses and spoke to significant gatherings, such as the annual Graduation Ceremony. He was unfailingly eloquent and inspiring, a statesman and later a highly respected Elder. His passing leaves a void, but his legacy of accomplishments and the memories he leaves of kindness, educational leadership, and collegial friendship will endure as long as the sun shines and the rivers flow.”

Anna-Leah’s career path mirrors many of her father’s footsteps: She, too, chose to further her education with a Master’s degree and then her PhD (2016), which focused on reclamation of Anishnaabe song and drum in education. She was a recipient of the University of Alberta Human Rights Education Recognition Award in 2013. She served as the Co-Director of the Aboriginal Teacher Education Program (ATEP) at the University of Alberta from 2008 to 2010. And she now works as a professor of Indigenous education and core studies and has been serving as the Faculty of Education Chair of Indigenization at the University of Regina for the past several years.

Virginia King’s Legacy

While it is clear that Anna-Leah has followed in her father’s rather large footsteps, she also follows in her mother’s less visible but no-less-valuable footsteps. For instance, Anna-Leah recalls 3 days of cooking massive pots of soup and making heaps of sandwiches at her friend’s granddaughter’s funeral and wake. “I thought of my mom, she would have done the same thing. My mom was always bringing soup to the friendship center in her down time,” says Anna-Leah.

Throughout her career, Virginia worked with Indian Affairs, eventually working her way to the role of director, with signing authority on treaty cards. “My mom was really proud. When I was between about 6 or 7, I went to Parliament Hill and did a march with her. The night before, we were making a placard and I was to write: ‘Indian women are women, too.’ I thought how can people think Indigenous women aren’t women, too? Bizarre! I didn’t have that feeling myself. I always felt accepted, and there wasn’t a big cultural gap. We proudly marched. My mom wasn’t brave enough, but she made me hold the sign. And I knew there was activism to do,” says Anna-Leah.

As a residential school survivor, Virginia didn’t talk much about her experience until later in life, but, “she did realize the wrong that residential school did in trying to snuff out the language and the culture,” says Anna-Leah.

Though her parents could speak Ojibwe, they did not pass the language on to their children. Anna-Leah says, “My mom and dad had a conversation about not teaching us the language so we would be successful at school because my dad was seeing the kids come in to school and struggle and struggle and then get turned off and eventually drop out because they were always behind.”

Other Teacher/Mentors

Another woman was influential in Anna-Leah’s life, her auntie, the late Mary Lou Fox-Radulovich, a member of M’Chigeeng (West Bay) First Nation and founding director of the Ojibwe Cultural Foundation, an organization formed to preserve Ojibwe, Odawa, and Pottawatomii Nations’ culture and language. Mary Lou was a teacher and language activist who also inspired, supported and worked alongside Cecil King. Anna-Leah had the privilege of spending a summer with Mary Lou at the Foundation.

“My dad must have asked if she could take me on as a summer student. I got to go there, and live with my grandmother at Wikwemikong. I would travel 45 minutes to M’Chigeeng each day. When I got there, Mary Lou came and gave me a warm hug and a kiss. I think the first day we went sweetgrass picking, and then we braided the grass. She joined us in braiding, and talked about how beautiful it was to be outside, to enjoy the wind, and to braid sweetgrass in the company of other women. I think ancestral memory was part of that day for her. I felt in an indirect way she was teaching us the power of that exercise. I really loved that. I felt in tune immediately with the practice and what we were doing,” recalls Anna-Leah.

The rest of the summer was spent in preparation for an Elder’s conference. The braids they had made were for the Elders. Anna-Leah says, “I was honoured to be making those braids for the Elders. Mary Lou was connected to Elders all over Canada, because she was trying to do something about the languages and cultures.”

Anna-Leah continues, “I learned a lot from her and the girls I worked with. I learned where the sweet grass grows. I learned to wear rubber boots, to not be afraid of anything that might be there. I learned smudging, and how to clean a porcupine with my bare hands. Delia Bebonang, an extraordinary quilt maker from M’chigeeng First Nation was there, so when the porcupine arrived, I worked with her. She showed me and I just followed and that’s what we did all day until we got the quills off. That was an awesome summer.”

At her first teaching job as the art teacher at Joe Duquette High School in Saskatoon, Anna-Leah met another teacher/mentor, the late Bowser Poochay from Yellowquill First Nation. Bowser recognized that they “were the same people,” honouring the braided ethnicity of the Anishnaabe and the Saulteaux peoples, which warmed Anna-Leah’s heart. The late Bowser and Maggie, his partner, adopted Anna-Leah and her daughter Tanis into their family, and in time they were also adopted into the community of Yellowquill, where she and Tanis participated in seasonal ceremonies.

Also during her time at Joe Duquette, Anna-Leah became friends with the late Elder Laura Wasacase, who also became her mentor. “An Elder, I had seen her here and there, and she smiled at me and said ‘Good morning.’ I was a little bit shy because I knew she wanted to converse with me. We became friends. Laura and her sister were instrumental in the formation of FNUC. She was inspirational. And open. She made me look up and smile and feel significant in the world. It’s such a cold place in the world. I try to be that way with younger people, I try to connect.”

Anna-Leah’s parents and mentors guided her as she navigated her way to the career in Indigenous Education that she has followed. Her father broke the trail.

Cecil King wrote that he had encountered many barriers in his career but because of his efforts, Anna-Leah has not experienced those same barriers. She says, “With all of his diplomatic movement and conversations and connections and how he acted in diplomacy, he created good positive relationships, and he had the backing of Indigenous people who needed somebody like him to do negotiations at the institutions. I think that he made White people Indian friendly.”

Anna-Leah continues, “He had to tolerate a lot—people weren’t as open, especially back then. He had a lot of hard people to deal with, to change their minds, to get them to accept, to not be fearful of preserving our language and culture. I know that he had good relationships. At U of S they said, ‘Your father walks on water.’ What they meant was that his words were profound to them. He was an orator, and University was a place where his oratory was accepted and appreciated. He would sooner speak something than write it. He loved giving a good oratory and he would always start his speech with his grandfather’s prayer and end with ‘Mii maanda didabaajimowin’ (These are my words) spoken in the language.”

Carrying Their Legacies Forward for Future Generations

Cultural and language revitalization, participating in ceremony, and building relationships through community involvement and service outweigh the academic, paper-writing side of Anna-Leah. Her current research projects reflect her interest in cultural reclamation. She also has a passion for Indigenous visual art, which has inspired her to develop a master’s course in Indigenous art. Becoming an artist herself is an as-of-yet unexplored path. She has, however, collected some art teachers, having taken a course with Degen Lindner (daughter of Artist Ernest Lindner) and Mina Forsyth, another renowned artist, and Lois Simmie, a watercolour artist, as well as taking a portraiture class. Anna-Leah may yet explore this path in when she retires.

As a parent, Anna-Leah has adopted her parents’ model of parenting. Her father was influenced most by his Kohkwehns, whom, he says, “taught me to encounter the world with joy and wonder. She taught me so many things by letting me experience that world, in contrast to the way Mama taught” (p. 160). Anna-Leah says, “I think about my parents and the subtle way they taught me—not a direct pedantic approach, more the suggestion of things, so I would come to the right conclusion. My dad was a mentor and a teacher, but not necessarily in a spoken way. One principle I value is to be the model for the kids, and hope that they will pick that up. That’s important.”

In a letter to her daughter Tanis, included in her dissertation, Anna-Leah described her understanding of her role in shaping future generations: She wrote, “Ever since you were born, I realized my reason to be. I had one important job and that was to see to your well-being and I can say I did my best. I may not have always been perfect but I sure did my best. You are my anchor in bringing me back to my purpose which is to see that you are loved and know you are loved. I always put your needs before my own as my parents taught me. And so I write this letter to once again centre myself as I look forward with you in mind to the task at hand in thinking about our future generations.”

Returning once again to her father Cecil’s valedictorian speech, about the advantage of having Indigenous teachers, lawyers, doctors … and the need for leaders, Anna-Leah is also fulfilling her father’s youthful vision: She is a teacher, professor and leader and her daughter Tanis is also following in their footsteps, having benefited from the trail her grandfather blazed, and will complete her training as a physician on May 24, 2023.

Footsteps left by her ancestors, such as the Anishnaabe seven grandfather teachings of love, respect, bravery, truth, honesty, humility and wisdom, and the oral traditions, songs and stories passed on from her grandparents to her parents have also served to guide Anna-Leah as she seeks to live inter-relationally, in honouring the earth and its creatures and all those who have gone before her and those who will come after her.

Anna-Leah says, “We always have one foot in the past, as that defines who we are, and one in the present, moving forward to the future. Ekosi! Mii maanda didabaajimowin.”

Follow us on social media