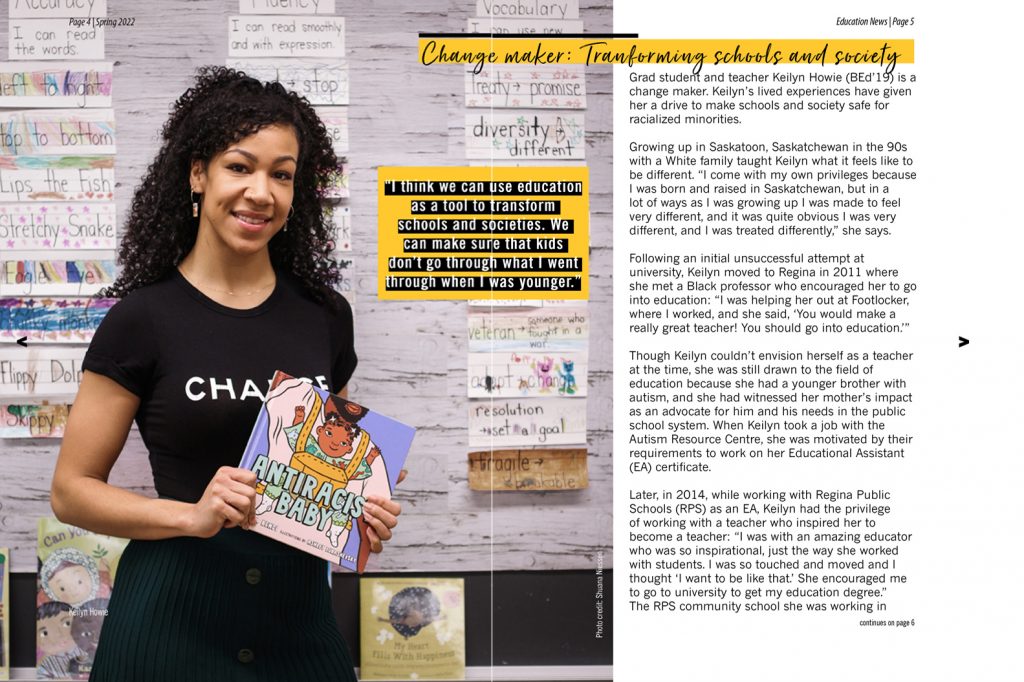

Grad student and teacher Keilyn Howie (BEd’19) is a change maker. Keilyn’s lived experiences have given her a drive to make schools and society safe for racialized minorities.

Grad student and teacher Keilyn Howie (BEd’19) is a change maker. Keilyn’s lived experiences have given her a drive to make schools and society safe for racialized minorities.

Growing up in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan in the 90s with a White family taught Keilyn what it feels like to be different. “I come with my own privileges because I was born and raised in Saskatchewan, but in a lot of ways as I was growing up I was made to feel very different, and it was quite obvious I was very different, and I was treated differently,” she says.

Following an initial unsuccessful attempt at university, Keilyn moved to Regina in 2011 where she met a Black professor who encouraged her to go into education: “I was helping her out at Footlocker, where I worked, and she said, ‘You would make a really great teacher! You should go into education.’”

Though Keilyn couldn’t envision herself as a teacher at the time, she was still drawn to the field of education because she had a younger brother with autism, and she had witnessed her mother’s impact as an advocate for him and his needs in the public school system. When Keilyn took a job with the Autism Resource Centre, she was motivated by their requirements to work on her Educational Assistant (EA) certificate.

Later, in 2014, while working with Regina Public Schools (RPS) as an EA, Keilyn had the privilege of working with a teacher who inspired her to become a teacher: “I was with an amazing educator who was so inspirational, just the way she worked with students. I was so touched and moved and I thought ‘I want to be like that.’ She encouraged me to go to university to get my education degree.” The RPS community school she was working in also affected Keilyn: “Education looked different in a community school, just the impact you could have as a teacher. I felt that I could contribute something, just through the relationships formed with students. Teaching is so relationship based, especially in a community school. I felt that who I am and my experiences and lenses would fit well in a community school setting.”

With all this encouragement, Keilyn finally decided to become a teacher. She entered the Elementary Education program at the University of Regina and found the experience life changing. “The first class was BAM, so eye opening;” Keilyn says, “Dr. Carol Schick’s class gave me the language to describe my experience. Growing up in Saskatchewan, we didn’t really talk about race and racism. Especially when I was growing up in the 90s, there wasn’t a lot of diversity; it was a pretty lonely world. I learned the language for the world around me, to name, recognize, and address oppression and racism in different forms. I’ve been drawn to this work in this field ever since.”

Reflecting further on Dr. Schick’s class, Keilyn says, “My identity was being validated in that class—to learn that this is how society is and that it needs to change. Before I had thought it was just me that needed to change. Even for the other students in the class to learn the language of anti-racism and anti-oppression … it wasn’t only my introduction to this language, it was also new to my peers. I remember another person in the class making sense of intersectionality and binaries, saying, ‘So if you’re a woman and you’re Black, it’s like a double negative?’ It was so jarring for me to hear that, but at least he was trying to make sense of it, and he was realizing that somebody who looks like me has a lot more to overcome than somebody who looks like him. Even with moments like that, as hard as they are to hear, there is hope: people are still learning, and people are changing, and it gives me much hope for the future.”

In her third year of university, Keilyn experienced her first Black professor, Dr. Barbara McNeil, who had encouraged her while she worked at Footlocker: “I think that shows how important representation is. I had lived my whole life with White teachers who never told me that I could be a teacher or that I would be a great teacher. I didn’t feel seen when I was growing up, didn’t see myself reflected in the classroom. I didn’t see Black kids in books or hear Black voices. It inhibited my identity growth for a long time.”

After graduating in 2019, Keilyn began her teaching career in a community school. Just one month later, she was challenged by the pandemic and the movement to remote teaching. The pandemic, she says “really opened my eyes to some of the inequities that community schools face, so I really wanted to become an advocate for these communities. That’s been driving me ever since.”

To make the changes that are needed, Keilyn is active with her Division’s Diversity Steering Committee and an Anti-Racist, Anti-Oppressive Advisory Committee. “All of these experiences over many years have put me in a place to speak and advocate for people in these communities, to advocate for the change that is so desperately needed in our Division, not only in community schools. The necessary conversations are being shied away from and I really want to be the voice to open those doors and make it seem less daunting to talk about what’s right, justice and equity, even with my young students.”

Now in her third year of teaching, Keilyn brings all of her personal and professional experiences, to her classroom of Grades 1 and 2 students at Thomson Community School in Regina. “I just love it here. Being a person of colour is really helpful in a community school. The demographics in a community school are diverse and representation is so important. With my experiences, I feel I’m able to connect with these students and even their parents who might be new to the country, or who might have some generational mistrust of schools.”

In her master’s program in education, Keilyn is planning her thesis and anticipates exploring anti-Black racism in Saskatchewan. “It’s such a big void, but it’s something I still personally experience and I’m from Saskatchewan so I can only imagine what other people are experiencing.”

Inspired by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission model, Keilyn says, “First there needs to be truth so we can get at what the issue is, how deep this issue is, what we even need to address, and then working on the action pieces to follow: How can we create these changes? How can we create more safe and inclusive spaces?”

With her work to make change in education, Keilyn hopes we can “re-imagine education. I think we can use education as a tool to transform schools and societies. [see K. Kumashira’s anti-oppressive model]. We can make sure that kids don’t go through what I went through when I was younger.” Keilyn summarizes with a quote by Ivan Fitzwater, saying, “The future of the world is in my classroom today.”

Keilyn’s Recommendations for Safe, Inclusive Classrooms

A foundation of belonging. Creating a classroom climate where kids feel safe and have a sense of belonging is important for them to learn. Keilyn says, “I’m intentional about making sure they all see themselves in the classroom. Even little things like this board on wall (see photo left.) My students love it. It builds that community.” This sense of belonging is fostered by several aspects in Keilyn’s teaching:

A foundation of belonging. Creating a classroom climate where kids feel safe and have a sense of belonging is important for them to learn. Keilyn says, “I’m intentional about making sure they all see themselves in the classroom. Even little things like this board on wall (see photo left.) My students love it. It builds that community.” This sense of belonging is fostered by several aspects in Keilyn’s teaching:

Conversations guided by great literature. Having a great selection of books with diverse topics and characters is Keilyn’s top teaching best practice suggestion. She says, “I don’t use a lot of pencils and papers, or worksheets. I teach through conversations, started with high quality literature. We have amazing conversations. Books are so important. I aim for three read alouds every day. I look for a books that match what I want to achieve. I don’t just read the book and move on. We talk about it. I ask them ‘What are your questions?’ which is more inviting than ‘Are there any questions?’ I am honest when I don’t know the answer to their question and we research it together.”

Responsive teaching. Part of creating a sense of belonging is being guided by the interests of students and their identities. Keilyn says, “I try to be culturally responsive. I use that globe all of the time because we are always talking about who we are as people and how we are all connected on this beautiful land. If I get a new student, we pull out the globe and look at where they come from and what languages they speak. If they are comfortable, they tell us about that, and we learn some of their language. It’s really important to me to let the kids be leaders and to introduce them to as many viewpoints as possible.”

Flexibility. Flexibility with daily plans is another aspect of Keilyn’s responsive teaching. “I’m very flexible–I have my day plans, if I veer from that, it’s okay. Listening to students and where they are at and what they are wondering might be the most important thing you do that day. If something negative happens, such as an experience of racism, stop your lesson to address what is happening because that will be the most important lesson of their day. We want students to feel seen and validated, so if we brush off their experiences or the things they are feeling, that’s not going to help them, the classroom climate, or the world. We have to address these things as they come up.”

Critical self-reflection. Keilyn adds that critical self-reflection is another important piece of developing a culture of belonging: “Teachers need to keep educating themselves about, for example, anti-racism. This is a pretty new field for a lot, especially in Saskatchewan. Teaching is so influential because were not just teaching the curriculum but also the hidden curriculum. If you don’t take the time to address your lenses or biases that you might be bringing, you might just be perpetuating those norms.”

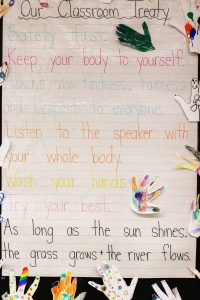

Decolonize and Indigenize. Keilyn is working to decolonize and Indigenize her classroom as well. Walking into her classroom, one immediately sees the bundles of wild sage hanging on the door, which were gifted to her class. The next thing you might see is the classroom treaty that she and her students develop at the beginning of each year. Keilyn explains this activity is “a simple way to talk about treaty and historical context.”

Using the resources she finds through the School Division, Keilyn develops new opportunities to start conversations about what people have experienced, what they did historically, how newcomer settlement affected their lives, and how to get back to learning on the land. “I invite a lot of guest speakers into the classroom and I have the school Elder come in once a week to spend times with kids.”

Follow us on social media