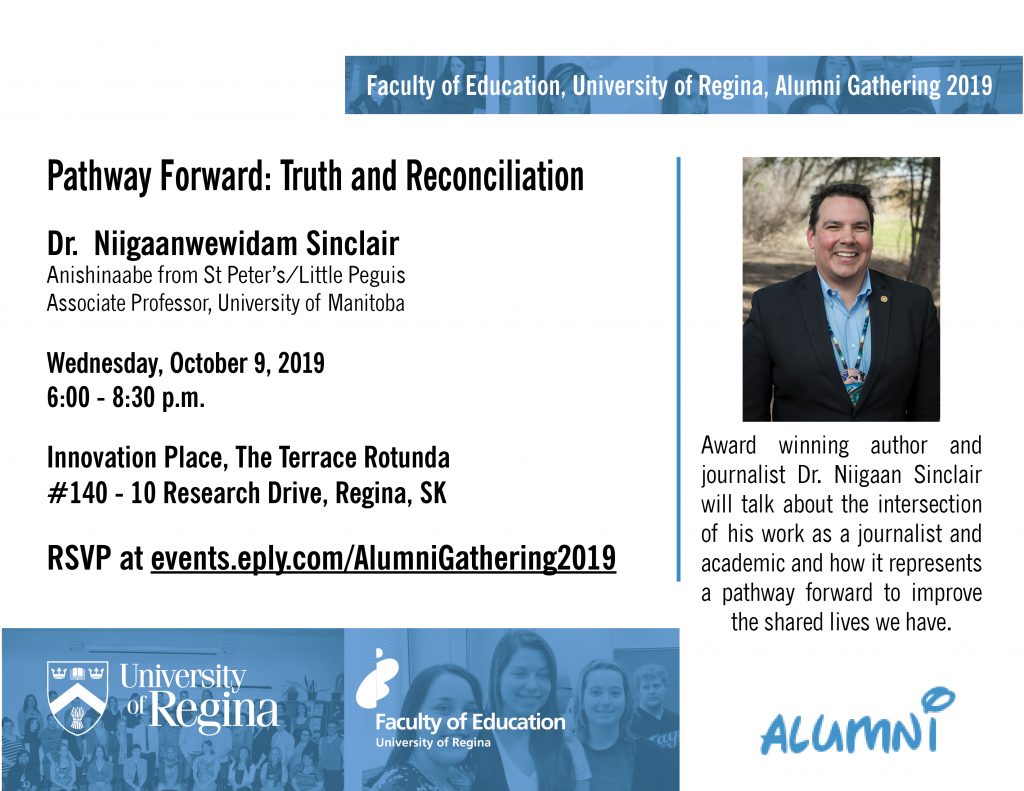

Alumni, take note of these events happening October 9. In the afternoon, an Indigenous Pedagogy Day and in the evening a presentation by Dr. Niigaan Sinclair.

Have you been wondering about the meaning and pronunciation of the Cree word “nanâtawihowikamik” when referring to the Faculty of Education’s Nanâtawihowikamik Healing Lodge and Wellness Clinic? This video will help you learn. Featuring Emerging Elder in Residence Joseph Naytowhow, Elder in Residence Alma Poitras, and Minority Language Professor Dr. Heather Phipps with Dr. Xia Ji, Dr. Melanie Brice, and Dr. Patrick Lewis. (Filmed by Dan Carr, Flexible Learning Division, and prepared by the Indigenous Advisory Circle chaired by Dr. Anna-Leah King)

What is the connection between horses, educational psychology, and Indigenous youth and culture?

Reconnecting with cultural and traditional ways of knowing and being is increasingly seen as a significant part of the healing and learning process for First Nations peoples, whose culture has been historically and systemically oppressed by the colonization process. Language revitalization has been a key focus of cultural preservation and reclamation, but Equine Assisted Learning (EAL) is a relatively new and less understood approach to learning and healing, at least among the scientific community. For Indigenous peoples, however, horses have long been viewed as carriers of knowledge and healers. The preservation of the critically endangered Lac La Croix Indigenous Ponies, then, is part of the process of cultural reclamation and preservation, and thereby healing and learning, as relations between Indigenous horses and peoples are (re)established.

Dr. Angela McGinnis, an Assistant Professor of educational psychology in the Faculty of Education and an Indigenous Health Researcher, and her graduate student, Kelsey Moore, are conducting SIDRU-funded research to better understand how and why Indigenous youth benefit from working with Indigenous horses, specifically the seven Lac La Croix Indigenous Ponies being cared for by Angela and her partner Cullan McGinnis at The Red Pony Stands® Ojibwe Horse Sanctuary. Founded by Angela and Cullan, the Sanctuary “is an Indigenous owned and operated not-for-profit.” The Sanctuary receives some financial support by private and corporate sponsors and donors; however, these supports do not cover all of the costs: Angela says, “The majority of the work and expenses fall on my partner (Cullan) and I to keep the ponies happy and healthy, both physically and spiritually. Our mission is to protect, promote, and preserve the critically endangered Lac La Croix Indigenous Pony breed.”

Angela, Cullan, and the Lac La Croix Indigenous Ponies all originate from Treaty 3 territory in Northwestern Ontario. Horses have been part of Angela’s life from her earliest memories at her home in Fort Frances. “I have a picture of me on a horse before I could even walk,” says Angela. Her parents were caretakers of Lac La Croix Indigenous Ponies and Nez Perce horses. Angela credits her father as a mentor who has taught her a great deal from his knowledge of working with horses.

Reconnecting with her Métis/Ojibwe cultural identities has been a focus of Angela’s education and healing. Cultural connectedness was a central concept in her research at Western University, where she received a PhD in clinical psychology in 2015. As part of her doctoral research, Angela developed a measure to assist in determining the extent to which cultural connectedness is associated with health and well-being, specifically among First Nations youth. Angela’s findings indicate that cultural connectedness is a positive predictor of mental health. This is critical knowledge because, as Angela says, “the mental health and well-being of youth is one of the most urgent concerns affecting many First Nations communities across Canada.” Angela views her work in educational psychology as “a perfect fit” for the research in which she is engaged. She says healing and learning are inseparable: “You can’t have healing without learning, or learning without healing.”

Since completing her doctoral research, Angela has been seeking to understand how cultural connectedness can be developed through, what she calls, “real-world experiences,” which include strengthened relationships with the land and all its “more-than-human” creatures, particularly the Lac La Croix Indigenous Pony. Broadening health research to include the more-than-human world is important to Angela because, she says, “We need to situate well-being within a larger network of social relations, with both the human and more-than-human worlds. We need to focus beyond the individual and extend our understandings about health and well-being to living in relation to all else, not just for the present but for future generations as well.”

With her expertise in psychology and her passion for the preservation of the Lac La Croix Indigenous Pony breed, Angela is perfectly situated to bridge, in her words, “often seemingly conflicting world views… I understand Western mental health perspectives, but this work requires an understanding of Indigenous perspectives of holistic wellness to fully understand the role of the ponies in the resilience process.” Angela likens the loss of contact with Indigenous horses experienced by Indigenous communities to the loss of family members: “Part of their family has been ripped away,” she says. Reconnecting Indigenous youth and adults with Indigenous horses brings about “indescribable moments,” says Angela. These moments spark the ‘I remember when…’ stories told by Elders about the ponies and traditional ways of life and are, Angela believes, charged with healing potential. “These are moments that could potentially change someone’s life. To see that happening in front of you, it’s a privilege.” Angela felt especially privileged to hear of the repatriation of the Lac La Croix Indigenous Pony to Nigigoonsiminikaaning First Nation, from which her partner, Cullan, originates. She says, “I was completely moved by the return of three black geldings to this community.” During a recent visit to see the community’s ponies, Cullan had opportunity to meet the geldings for the first time. Angela says, “The reunion of these family members was so powerful—an emotional reuniting. The bond between the geldings and Cullan was instant. It’s a culturally specific relationship that dates back to pre-Colonial contact. This type of relationship can’t be replicated with any other breed of horse.”

Reunions such as these lead to the beginning of relationships with the more-than-human world, and are what Angela calls a “doorway to the culture,” which can help youth make other cultural connections, such as ceremony. For instance, Angela and Cullan’s relationship with the Lac La Croix Indigenous Ponies at the Sanctuary has meant that they have sought guidance from local traditional Elders and engaged in horse-specific traditional ceremonies held in communities, such as the Horse Dance. Angela would like to share the doorway experience with her Educational Psychology students: “I want to help students step through that doorway. That’s how we understand how to help others, by experiencing it ourselves. And in return we help the ponies. That’s the whole mutual helping process, helping the horses in their fight against extinction. We need the Lac La Croix Indigenous Ponies as much as they need us,” says Angela. She plans to start bringing her students out to the Sanctuary for classes in Spring. A 20-foot tipi will be raised as Angela prepares to bring her students in contact with the ponies and the land.

Master’s student Kelsey Moore, who received a B.Ed. in Indigenous Education from First Nations University of Canada, is now undertaking her M.Ed. in Curriculum and Instruction at the University of Regina under the supervision of Dr. McGinnis and the mentorship of Life Speaker Noel Starblanket. Kelsey is Métis and grew up in Yorkton. Her lifelong passion for horses began with several summers spent working with youth at horse camps and riding stables and continued with her experience of getting to know the Curly Horse breed at her inlaws’ farm. Her thesis research question perfectly intersects with Angela’s interest in understanding and offering evidence-based research to explain how and why Indigenous youth benefit in both educational outcomes and mental health, through establishing relationships with horses and how Equine Assisted Learning programs can be successfully culturally adapted.

Kelsey and Angela are amazed to have found each other. Angela says, “What are the chances of me finding a student who wants to work with Indigenous horses?” The two researchers are working toward the same ends as those involved in language revitalization: “We are all tackling a shared goal: Cultural preservation,” Angela says. The actual preservation of the critically endangered Lac La Croix Indigenous Pony extends as a metaphor for cultural and identity preservation: “Their mere presence is a counternarrative to the colonial narrative of the extinction of Indigenous horses to the Americas,” says Angela. Indeed, the Lac La Croix Indigenous Pony’s survival itself inspires hope. But beyond that, Angela feels that interaction with Indigenous horses gives “Indigenous youth opportunities to connect with horses who have resilience and strength, like their own, that they can identify with, a culturally specific story,” she says.

What exactly is Equine Assisted Learning (EAL)?

Snowshoe and Starblanket (2016) state that EAL “is a relatively new approach to knowledge acquisition that draws primarily on the tenets of experiential learning, that is, learning through hands-on experience with the horse (Dell, Chalmers, Dell, Sauve, & MacKinnon, 2008).”

To deepen her understanding of EAL, Kelsey received EAL certification in August at Cartier Farms, near Prince Albert. Cartier Farms teaches that establishing an experiential hands-on working relationship with horses, with their sensitivity, non-verbal communications, resilience, and forgiving ways, can be an effective approach to learning, to self-knowledge, and to self-evaluation.

Angela, who has been guided by the traditional Elders, Knowledge Keepers, and communities with whom she has worked, sees the potential for healing and learning in culturally adapted EAL. Angela views horses as “more-than-human co-constructors of knowledge.” Horses have much to teach us about the land and living on the land, she says. Elders and Knowledge Keepers have taught Angela that, with their four feet always on the ground, horses have a greater connection with Mother Earth, and through this connection, the Creator. Thus, traditionally, horses have been considered a source of maintaining and recovering holistic wellness.

Upon the arrival of Angela’s first Pony at the Sanctuary, a beautiful stallion, affectionately named Sagineshkawa (Pleasure with my Arrival), she says, “I realized that I should not rush things. I needed to slow down and have humility, especially around a powerful being like a horse…This was the horse that I had to pay attention to and listen to spiritually.” Angela is grateful to all her ponies for their patience in teaching her. Kelsey’s experiences with horses have similarly given her the understanding that she must “slow down and be present in the moment,” she says. “Helping humans slow down is a way that the horses care for us,” says Angela. She views the horse-human relationship as one of mutual caring: “We are caretakers of them and the land, but the ponies also take care of us.”

Yet, there is an urgency that requires speed in this research due to the need for Indigenous youth to be able to access culturally adapted healing and learning programs. As a mother of a toddler, Kelsey had intended to move a bit slower with her research, but she says everything is moving much quicker than she planned or expected. Kelsey’s research, using what Angela describes as “a pure Indigenous research method,” seeks to understand the spiritual and cultural connections between Indigenous youth and Indigenous horses. Incorporating ceremony as research, Kelsey is documenting her interactions and deep listening experiences with the ponies, along with the conversations she has with Elders and Knowledge Keepers to make sense of what she observes.

The two researchers are already envisioning and talking about future plans. Angela says, “We hope to apply for an operating grant to help Kelsey set up her own Indigenous-centered Equine-Assisted Learning and healing program in the community, following the completion of her academic work.”

The Sanctuary has recently gained international attention. It will be featured in a short documentary film currently being produced by National Geographic as part of the Natural Connections Project. The film will document how EAL contributes to the well-being of First Nations youth. Through the film, Angela hopes to showcase “how Indigenous communities are using horses to connect with culture, strengthen positive relationships, and learn through activities with horses and nature.”

By Shuana Niessen

Credits for photos below: Shuana Niessen 2018

In October 2018, the Faculty of Education’s emerging Elder in Residence, Joseph Naytowhow, a Plains/Woodland Cree (nêhiyaw) singer, songwriter, storyteller, actor, and educator from the Sturgeon Lake First Nation in Saskatchewan, was recognized by the Saskatchewan Arts Board with an award for his contributions to arts and learning. Naytowhow says this award is significant to him, attributing the recognition to “the children and the people I work with, the teachers, and educators, and I share this award with them.”

In October 2018, the Faculty of Education’s emerging Elder in Residence, Joseph Naytowhow, a Plains/Woodland Cree (nêhiyaw) singer, songwriter, storyteller, actor, and educator from the Sturgeon Lake First Nation in Saskatchewan, was recognized by the Saskatchewan Arts Board with an award for his contributions to arts and learning. Naytowhow says this award is significant to him, attributing the recognition to “the children and the people I work with, the teachers, and educators, and I share this award with them.”

This isn’t the first award for Naytowhow, whose work has been recognized by several awards: the 2006 Canadian Aboriginal Music Award’s Keeper of the Tradition Award, a 2005 Commemorative Medal for the Saskatchewan Centennial, the 2009 Gemini Award for Best Individual or Ensemble Performance in an Animated Program or Series for his role in Wapos Bay, the 2009 Best Emerging Male Actor at the Winnipeg Aboriginal Film Festival for his role in Run: Broken Yet Brave and the Best Traditional Male Dancer at the John Arcand Fiddle Fest.

Naytowhow says he appreciates the awards he receives from Saskatchewan, valuing them as “gifts that validate that I have needed both worlds. They’re inseparable.” He considers the awards, as “marking posts in my life that indicated to me that I was someone who had something to share, —I think it validated what I was doing in the spiritual and cultural worlds: nêhiyaw (Cree person) and nêhiyawêwin (speaking Cree), practicing nêhiyaw-isîhcikêwin (Cree culture and ceremony). All I was doing was Indigenous ceremony and culture because that was my life force, my life source.”

At the same time it is difficult to receive the awards because, for Naytowhow, art was never about recognition. He says, “Sometimes you don’t believe it when you’ve been given an award because it’s come from the place that you’ve suffered through and healed through…Everything that I did was about healing. Returning to balance. Everything was about that.”

Naytowhow has invested a lifetime in healing from the trauma of being taken from his family and community at the age of 6, and placed in Indian residential schools for the next 13 years.

“What I went through is one thing, right, 13 years of residential school, is one thing, but you never really understood what you were experiencing academically in education. It didn’t make sense. I didn’t come from that world. I didn’t come from Shakespeare; I didn’t come from math, or from overseas, and yet I was totally immersed in that, and just totally struggled to get through it every step of the way.”

When Naytowhow graduated from highschool, it wasn’t due to academic achievement: “It was like a bull dozer going through a big mud pile, just edging along. I finally got pushed out of that system with a fifty average. I think they just wanted to get me finished. I was really a below average student according to my marks. I was really a very silent learner and you can’t be a silent learner in this system; you have to speak, you have to present, you have to do it their way. And it never really resonated with me,” he says.

After residential school, Naytowhow spent his youth in search of himself. His search for harmony and balance began with attempting to live in the colonial culture. Knowing that education was important to earn a living, Naytowhow, who enjoyed athletics, found a physical education program at a university in Calgary that would accept him with his grades. The program was more about physical performance than academics, and, Naytowhow says, “I did really well; it was all based on skill. I excelled and the first semester my marks were good so I immediately applied to the U of R.” Naytowhow was accepted into the Faculty of Education, but struggled through the next three and a half years before withdrawing from the program. “I was still trying to make sense of this culture that was imposed on me and I sort of got it, but I sort of didn’t. I just barely squeezed by. … I would try to read and I would read for a while and I would fall asleep. I was reading some scientific theory and my mind wanted to write a poem,” he says.

However, after withdrawing from the education program, and while he was working as an Education Liaison for the Friendship Centre, Naytowhow realized that without a degree he wasn’t being taken seriously by the educational administrators, so he decided to finish his Education degree, but this time through ITEP {Indian Teacher Education Program) at the University of Saskatchewan. His practicum took him north to Stanley Mission, to a federally funded school. Naytowhow graduated with a B.Ed., but he didn’t stay in the teaching position he acquired due to a lack of support from the administration.

As Naytowhow continued his search for fulfillment and self, he drifted from job to job, moving from the North to the South, to the further north (NWT) and then back again, trying to fit into the protestant work ethic of 9 to 5 work: “There was something about my experience at residential school that affected my ability to, not so much retain jobs, but stay in a job for any longer than two years. For some reason it was the limit of my mind and body. So I would move; I would want to move: miskâsowin (finding oneself), and opapâpâmacihôs, (moving about in life), that searching for oneself. I wasn’t really fulfilled in the position I was doing. So I would just resign and take off.”

Having children made life a more serious affair and Naytowhow did what he could as a parent to try to maintain stability. He says, “I started being a father and looking after my kids as much as I could within the kind of terrible child rearing that I got through residential school. Some was good, you know; it wasn’t all bad, but it was basically being parented by surrogate parents who didn’t—who couldn’t really take the time to train you to be a young man, a responsible young male, or human being. They just didn’t have time. There was no way they could raise me like a son. So I was trying to raise my own kids from a place of no parenting skills, not learning how to be intimate, not even knowing if I could maintain a job. …. But all along, I really was not feeling fulfilled as a human being, as a male, as a man. I wasn’t being all that society requires for one’s life to be in harmony and in balance, like having the 9 to 5 job, or having a steady income. It happened but it didn’t really make any sense to me.”

What did make sense, what always made sense to Naytowhow, was culture and ceremony: “Singing with the elders or praying with the elders, that was what made sense to me, of anything I was experiencing. The Canadian culture, the protestant work ethic, just didn’t make any sense to me.”

All through his healing journey, Naytowhow was developing an awareness of his Indigenous roots, what he had left behind at the age of 6, the lost memories of loving relationships and experiences with family members and his community. It started first with a realization in his 20s that he was Indigenous (not Canadian as he had been taught), and then the gradual addition of Indigenous culture and ceremony to his life.

While attending the University of Regina, Naytowhow picked up a drum for the first time: “I had a strong urge to go to the drum. I never looked back, ever since I hit that drum.” A visiting visual arts professor from the state of Washington, Leroy of the Yakama tribe, and a colleague, Tim of the Umatilla tribe, introduced him to the drum: “From there,” Naytowhow says, “I went into powwow, into the Sundance, into all the other ceremonies connected through a drum. The drum moved me into the sacred music and songs, and that totally made sense for me to do.”

Naytowhow explains: “My soul was calling out, was being called out, to the elders and ceremonies; that was where I was supposed to be; that was supposed to happen, and I absolutely totally trusted that intuitively.”

“The gifts of music and song and stories that I got from the elders, those were the most critical and most important [awards] that I needed to keep this being alive on this planet. Cause when you’ve gone through residential school, you’ve got extreme trauma that you have to deal with and its always going to be there. Even to this day I still experience pockets of anger and depression and just dark holes that I can’t make sense of, but those stories, or ceremonies, or laughter, anything to do with that, I just had to be there, I had to go there.”

The wisdom of age and experience has given Naytowhow the understanding that “what went wrong, when I went into the colonization culture, was that I tried to be a part of it 100%. I just had to be in and out of it. Had to find short term work and depend on that. That’s probably why I became more a musician and storyteller, became an artist. It was far more flexible and fulfilling as a singer, as someone fascinated by story and fascinated by culture, and I slowly got into acting. For me, I could live there.”

The first time Naytowhow began to consider himself a practicing artist was when he started a residency in Meadow Lake as a storyteller, between 1995 and 2000. He then thought, “Ok, now I can make a living being an artist, being a musician, putting out an album now and then, travelling to storytelling festivals, to music festivals.” His healing journey became the source, he says, “whereby my art practice would flourish and my cultural and spiritual practice. Healing was more a spiritual and cultural journey, more that part, and the art kind of came out of it as a result.”

The Saskatchewan Arts Board Award came with $6000, which is something Naytowhow really appreciates because it allows him to focus on his art: “As an artist, I just need to do the art. But I can’t do it when I’m doing presentations in different areas and being pulled all over. What I need is just some financial support to pay bills and pay my rent. And then I can do songwriting…the things that I do anyway, but I’ve never really been focused as an artist.”

Naytowhow’s healing journey, reconnecting with Indigenous culture and ceremony, and expressed through the arts and education, keeps him connected to both worlds. His presentations begin with Cree concepts, and he relies on the wisdom of the old people to guide him as he educates students. The balance and harmony he has found reflects his Indigenous name, which means “guided by the spirit of the day.”

By Shuana Niessen

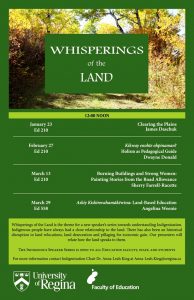

Whisperings of the Land is the theme for a new Indigenous Speaker’s Series towards understanding Indigenization. Indigenous people have always had a close relationship to the land. There has also been an historical disruption in land relocations, land desecration and pillaging for economic gain. Our presenters will relate to how the land speaks to them.

Whisperings of the Land is the theme for a new Indigenous Speaker’s Series towards understanding Indigenization. Indigenous people have always had a close relationship to the land. There has also been an historical disruption in land relocations, land desecration and pillaging for economic gain. Our presenters will relate to how the land speaks to them.

The first speaker will be Dr. James Daschuk, author of Clearing the Plains.

January 23, 2018 at 12:00 p.m. (noon)

Education Building, Room 210

The Indigenous Speaker Series is open to all Education faculty, staff, and students.

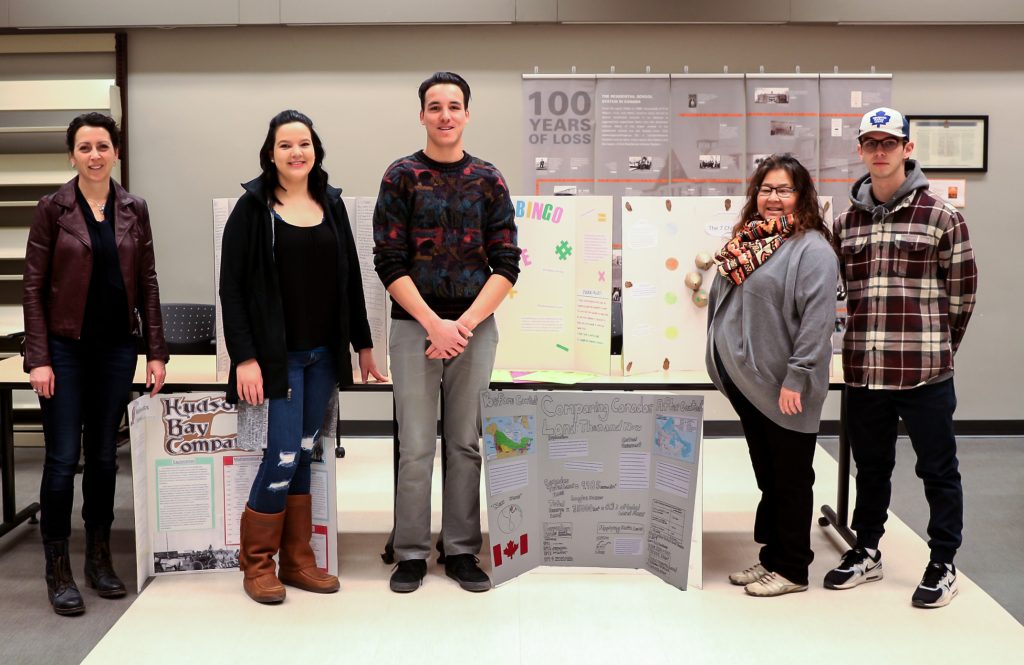

On December 11, 2017, Math 101 students held a mini Math Fair, presenting their posters which reflected the Indigenization of mathematics concepts. (see photos above)

The concept of Indigenization is identified as “one of the University’s two overarching areas of emphasis” within the 2015-2020 Strategic Plan (https://www.uregina.ca/strategic-plan/priorities/indigenization.html). Depending upon the definition consulted, Indigenization may or may not be considered the work of settler/immigrant Canadians for it involves first-hand revitalizations of First Nations, Inuit and Métis languages, legal systems, and ceremonies, among many other aspects. Indigenization, however, lies in relation with decolonization and thereby challenges all Canadians to work at disrupting and changing current institutions and systems, including those educational. Thus, as a doctoral candidate of mathematics education, Shana Graham has been studying Indigenization and decolonization so as to inform her dissertation research which involves (re)imagining possibilities for mathematics education.

The idea for the implementation of a Mathematics 101 final project as poster and Mini Math Fair was informed by Show Me Your Math: Connecting Math to Our Lives and Communities, a program developed by Dr. Lisa Lunney-Borden and Dr. David Wagner (http://showmeyourmath.ca/). While a final poster project is not unusual within education courses, it is unique to a Mathematics 101 course. Decolonization, however, encourages considerations of context/community, which for this particular mathematics course involved only preservice teachers from the Saskatchewan Urban Native Teacher Education Program (SUNTEP-Regina). Thus, in adapting/decolonizing curricula for context/community, the arguments presented for changing the Mathematics 101 final evaluation from exam to project were accepted by Dr. Shaun Fallat, Head of the Department of Mathematics & Statistics. The support of Dr. Fallat and the Dean of Science, Dr. Farenick, need be acknowledged for reconciliatory acts may not otherwise be possible without the support of such powerful individuals.

Graduate students with diverse backgrounds have come together with a common goal of decolonizing adult learning.

The graduate course, Trends and Issues in Indigenous Adult Education, explores research, theory, and the practice of trends, issues, and perspectives in Indigenous learning.

Students from six countries were in the class from Brazil, Canada, Nigeria, Pakistan, South Africa and Sri Lanka. The diversity speaks to the higher number of international students who are choosing to further their studies at the University of Regina.

Having such a mix of backgrounds and viewpoints in one class made for some eye-opening perspectives on trends and issues involved in decolonizing adult learning in order to improve Indigenous education.

The class was led by Dr. Cindy Hanson, Associate Professor of Adult Education/Human Resource Development in the Faculty of Education.

“The class was important in this case because it was a coming together of international and Indigenous students in a very organic way and with a broad range of understandings regarding history, culture, and politics in Indigenous Adult Education,” says Hanson. “The course offered an opportunity to put this into practice. Experiences from the field of adult learning were built into the content.”

Many also feel little has been done to build structures and programs in communities for adult learning about decononization and Indigenous issues. They see this class as a good start. The students appreciated the participatory approach to Hanson’s class, allowing for discussions.

José Wellington Sousa is from Brazil and is working on his PhD in Adult Education at the U of R. He has earned a BA in Economics and a Masters of Science in Administration at the University of Amazonia in Brazil.

“The class was a great example of what is going on in Canada right now. I can see the diversity in the classroom. We can learn from each other. We had many nations and sharing and reflecting on Indigenous education,” says Sousa. “In Brazil, we are kind of behind in the discussions of decolonization. So we are not even talking about reconciliation and addressing the injustice. I see this class as an opportunity to understand and learn.”

Issah Gyimah, who earned his Bachelor of Education at the University of South Africa, grew up in the post-Apartheid era. He’s taught in South Africa, South Korea, and Saudi Arabia. He started his studies at the U of R in September.

“Coming from Africa and knowing about Apartheid, colonization, and racism, I have learned a lot from here and this class,” says Gyimah. “It has changed my perspective on how I see things. This class is a good foundation.”

Gyimah points out that adult education in South Africa is a growing area and a field that is not completely developed.

“We’ve been looking at children, but adults have influence on the children. There is a backlog of adults who did not get an education so this has left a big gap in South Africa,” he says.

Pauline Copland earned her Education Degree from Arctic College in Nunavut. She’s working towards her masters in curriculum and instruction at the U of R. Her first language is Inuktikut.

“From the readings and talking to my classmates, I learned things about our Canadian history, even my own history, like residential schools. It affected who I am without knowing,” says Copland, who appreciates the class diversity. “Compared to where I went to school, coming here looks like the whole world is here. The diversity is really nice, meeting people from different countries.”

The class includes one student from Saskatchewan, who sees her experience and diverse views as an asset that will help her down the road.

Chantelle Renwick has a Business Degree from the U of R and a graduate diploma in teaching from New Zealand. It was her experience in New Zealand that started her passion for Indigenous education. She’s working on her masters in Indigenous Education.

“What we hear over and over is that colonization has happened in so many part of the world and that Indigenous people have been dealing with the loss of culture and language,” says Renwick, who is an instructor of Office Administration at Saskatchewan Polytechnic in Regina.

“You realize with such a diverse class the different history and different feelings and perspective that the adult learners bring to the classroom. You become more conscious about the impact colonization has on people.”

The final class December 5, in the presence of elder Alma Poitras, featured a discussion about what the students learned and how it could be applied to their workplace or personal lives.

The classes also featured speakers including elders, a speaker from the Office of the Treaty Commission, a Metis lawyer storyteller, a talk by the U of R’s James Daschuk author of Clearing The Plains, and a fieldtrip to the Royal Saskatchewan Museum led by curator Dr. Evelyn Siegfried.

“Decolonizing adult education is a current theme in the field of adult education and a critical perspective on how to do this with a range of learners is important,” says Hanson.

The University of Regina has enjoyed an increase of graduate students. As of the Fall 2017, 1,902 graduate students are furthering their studies at the University.