– by Kaetlyn Phillips

Language is a complex and can influence design and response in multiple ways. As Pew Research (2023) summarizes in their Writing Survey Questions Methodology, word choice and phrasing, even small differences, can change respondents’ understanding of a survey question and affect their responses. So, I thought I would take a look at a recent survey from Angus Reid Institute on Canadian Cultural Mindsets to provide examples of survey question design and wording.

If you’d like to take the survey, I recommend doing it before reading the rest of this blog. It’s okay, I’ll wait.

Are you done? Let’s continue…

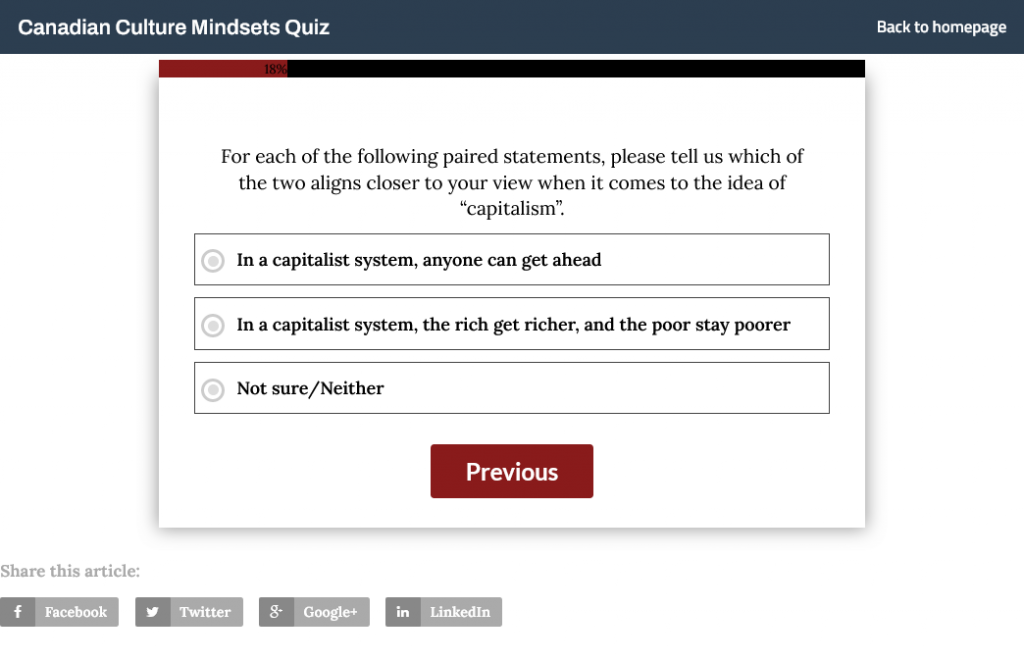

The first thing to consider when organizing a survey is the placement of questions. Designers want to avoid the context effect, which is when questions asked earlier in a survey influence choices later on. For example, in the Canadian Culture Mindset Quiz, Angus Reid Institute asked questions about opinions on capitalism and distribution of wealth. The first question they asked was “For each of the following paired statements, please tell us which of the two aligns to your view when it comes to the idea of ‘capitalism’.”

Image: screenshot of Canadian Cultural Mindsets Quiz, Angus Reid Institute, 2023

This question was asked before any other more detailed questions about opinions on capitalism and wealth distribution, including questions on wealth tax and a tax on property sales. By first asking general questions about opinions on capitalism, the Angus Reid Institute avoided influencing or changing respondents’ answers. For example, asking the more specific questions about possible wealth taxes first, when people typically respond negatively to new taxes, could influence respondents’ opinions on capitalism in general.

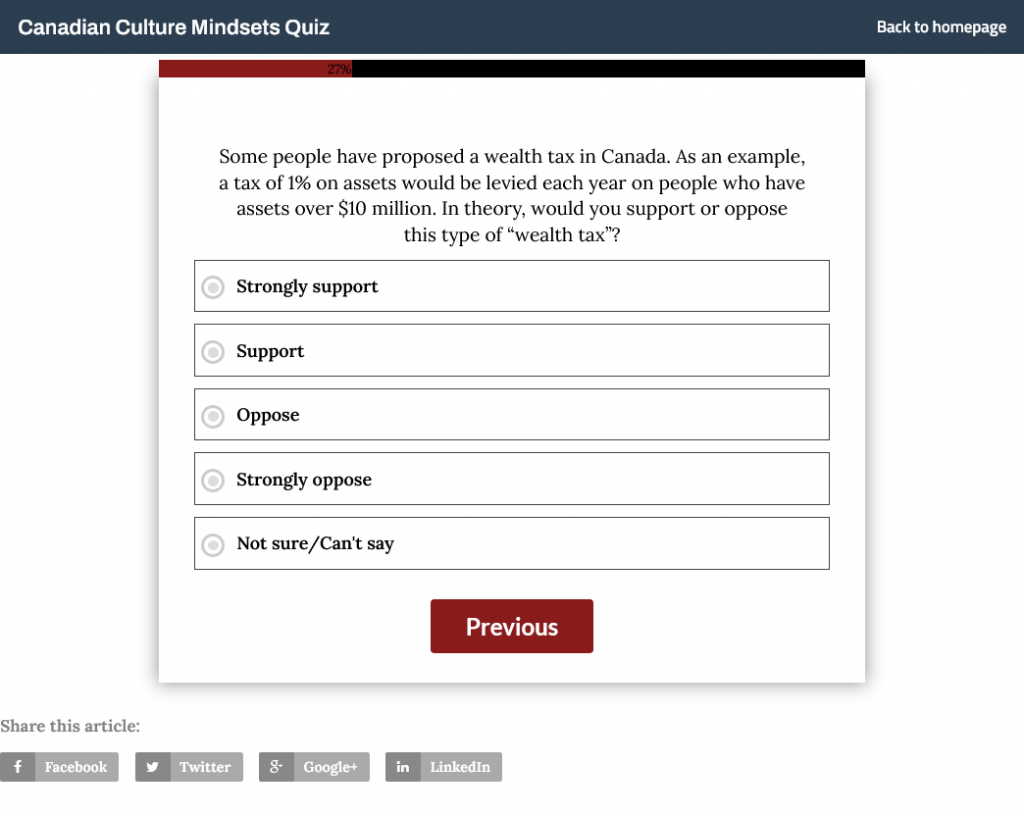

The question also demonstrates the fine balance between providing information to prompt the participant on a topic, while not providing too much information that participant is overwhelmed, frustrated, or bored. Too little information results in an imprecise answer or skipped answer (i.e. “I don’t know what this is, so I’m not answering”) and too much information also results in an imprecise answer or skipped answer (i.e. “OMG I’m not reading this I don’t care that much”). The question on a wealth tax attempts to find this balance.

Image: screenshot of Canadian Cultural Mindsets Quiz, Angus Reid Institute, 2023

The question “Some people have proposed a wealth tax in Canada. As an example, a tax of 1% on assets would be levied each year on people who have assets over $10 million. In theory would you support or oppose this type of ‘wealth tax’?” allows participants to make their judgement based on an example of a wealth tax without having to consider their existing knowledge of wealth taxes.

If the question had been written differently, for example, “The Liberal government has proposed a wealth tax in Canada … Do you think the federal government should enforce a ‘wealth tax’?” responses would be very different and the question could prime and push respondents to answer a specific way. Priming is when the initial wording is leading and makes the respondent think a specific way about the topic. Starting with “The Liberal government” is going to prime respondents to consider the question based on their political affiliations, which will bias their response. The push comes from the last part of the question “Do you think federal government should enforce a ‘wealth tax’?” The influence of political affiliation and the word choice will push respondents into a specific choice.

Which bring us to the final aspect of survey design and question wording we will be discussing today: acquiescence bias and social desirability bias. Survey questions that require Yes/No and Agree/Disagree options tend to overstate approval rates because humans really want to be liked and just naturally tend to agree with a statement when the options are to only agree or disagree. Pew Research recommends using forced choice questions to get around acquiescence bias. Social desirability bias can be reduced by allowing respondents to complete the survey privately, but cannot be fully removed. Another way to get around these biases is to ask a similar question in a different format and compare responses.

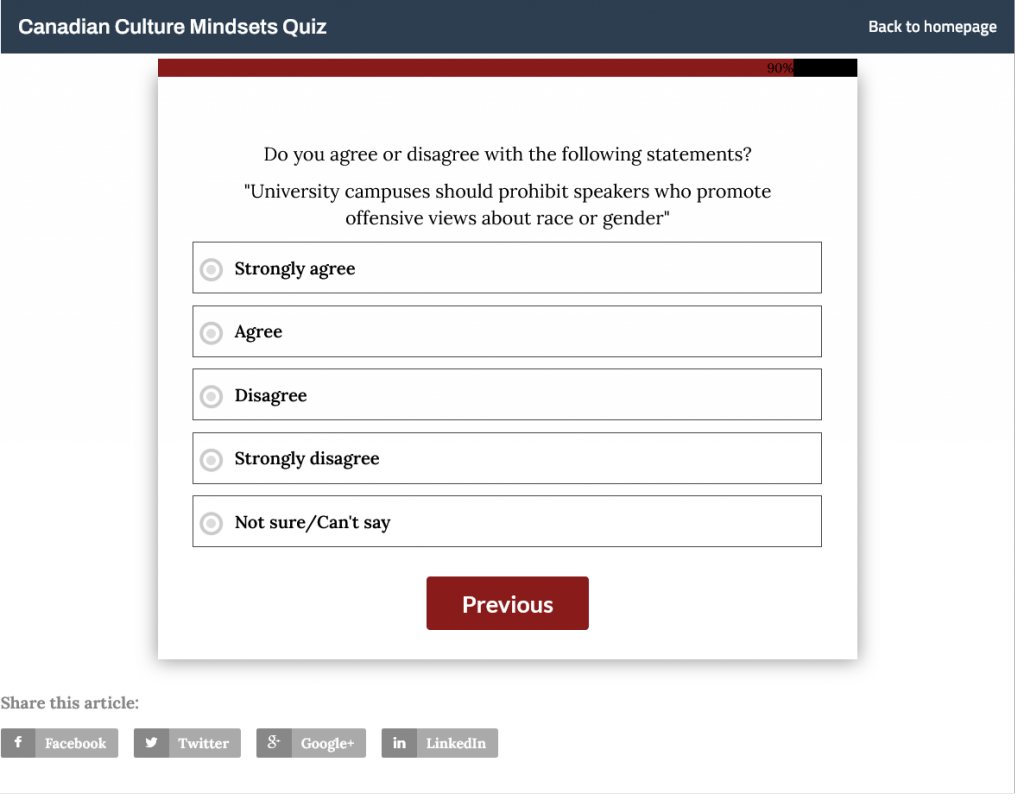

For example let’s look at this question on freedom of speech:

Image: screenshot of Canadian Cultural Mindsets Quiz, Angus Reid Institute, 2023

The question “Do you agree or disagree with the following statements? ‘University campuses should prohibit speakers who promote offensive views about race or gender’” is an Agree/Disagree question about a sensitive topic. It’s possible that respondents will be more likely to choose agree because of bias; although, having a scale of options will reduce the bias.

However, Angus Reid Institute follows up with a different question about a similar topic.

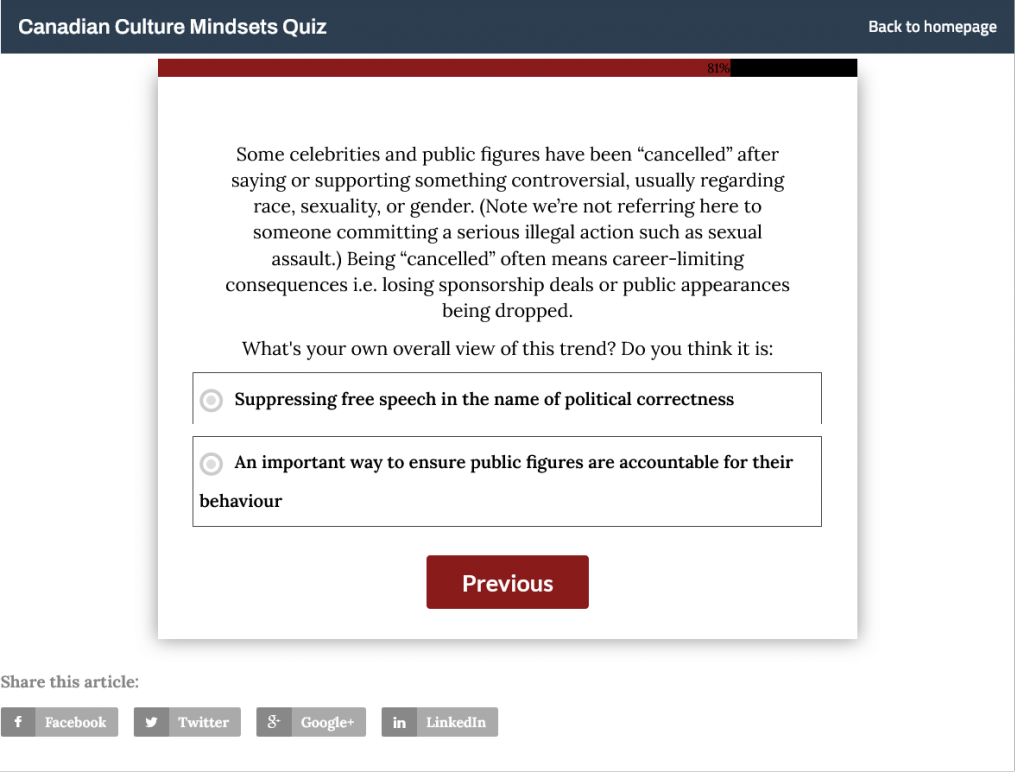

Image: screenshot of Canadian Cultural Mindsets Quiz, Angus Reid Institute, 2023

This question “some celebrities and public figures have been ‘cancelled’ after saying or supporting something controversial, usually regarding race, sexuality, or gender. (Note we’re not referring here to someone committing a serious illegal action such as sexual assault.) Being ‘cancelled’ often means career-limiting consequences i.e. losing sponsorship deals or public appearances being dropped. What’s your own overall view of this trend? Do you think it is:” uses the forced choice option to reduce acquiescence bias. Both of these questions measure beliefs on freedom of speech and political correctness, but ask the question in different ways. If the responses are similar, then we know the potential bias of the Agree/Disagree question was reduced.

Surveys like the Canadian Cultural Mindsets need to be well designed as they are discussing sensitive topics about people’s lives and attitudes. If the wording is not precise, it’s possible the results will be dismissed due to bias. We also need to keep in mind that the analysis shared by these surveys shapes public policy. If we encounter poorly written surveys, we need to be critical of their intentions.