We’ve moved our blog to a new website, please visit yoURArcher to see some exciting upgrades which gives you a better reading experience.

We’ve moved our blog to a new website, please visit yoURArcher to see some exciting upgrades which gives you a better reading experience.

We are happy to report that the Regina and Wascana Rooms, as well as our archival retrieval service, are now back to normal after a busy summer of basement renovations. Thanks for your patience and support!

The Dr. John Archer Library & Archives is excited to announce our new authentication system for access to electronic resources! Users will enjoy the same level of access as before, but with several additional benefits:

Please note that EZProxy links will still work as the Library is transitioning to this new system. For questions, please email Library.Help@uregina.ca.

The University of Regina’s institutional repository, oURspace, will be migrating to a new national repository platform, Scholaris. As a result, oURspace will be unavailable from Monday, August 18 to Wednesday, August 27, 2025.

Once the migration is complete, oURspace will have a new URL. Redirects from the old address will be set up to help users transition smoothly.

If you have any questions about Scholaris or the oURspace migration project, please contact ourspace@uregina.ca.

Congratulations to our Archer Book Club 5 Year Celebration winner for their outstanding review of Animal Farm by George Orwell! We received an amazing 88 submissions, and we want to give a big THANK YOU to all participants!!

Check out the contest page for the winning review and honourable mentions:

Our Fall 2025 Book Club sessions are all books that are being adapted into new films:

• Wednesday September 24, 2025 – 12pm (online) – The Housemaid by Freida McFadden, hosted by Brandi Adams. Film release set for December 2025.

• Wednesday October 29, 2025 – 12pm (online) – Frankenstein by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelly, hosted by Arlysse Quiring. Newest film adaptation release set for November 2025, directed by Guillermo del Toro.

• Wednesday November 26, 2025 – 12pm (online) – Project Hail Mary by Andy Weir, hosted by Jennifer Hall. Film release set for March 2026.

To attend any meeting, please email Arlysse.Quiring@uregina.ca. All faculty, students, staff are welcome.

Jump into our Summer Movie Contest for a chance to win prizes: library goodie bags, Starbucks gift cards, and more!

Who can enter?

Registered University of Regina students

Deadline:

August 26, 2025

How to enter:

Swing by the Archer Library Entrance Display, scan the QR code, grab a bookmark or mood pencil (while they last), and check out our movie-themed display.

Or just enter online here: Summer Movie Contest Guide

Celebrate 5 years of reading with the Archer Book Club! In June 2020 we began the virtual club both as an outreach initiative during trying times and as a way to form a community of readers on campus.

We select three books per semester and have strived to cover as many authors, subjects and genres as possible. Some of our absolute favourites over the years have been Homegoing (Yaa Gyasi), The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek (Kim Michele Richardson), Born a Crime (Trevor Noah), The Song of Achilles (Madeline Miller), and Rebecca (Daphne du Maurier).

We’ve also had the great pleasure of hosting guest authors and speakers, as well as partnering with both the UR Alumni Association and UR Press. Our book club archives offer details on each book and guest over the years.

To celebrate these years of reading and wonderful discussion, we have launched a reading contest. Just tell us your favourite (or least favourite) recent summer reads and you could win a Starbucks gift card! All details can be found at our library guide, on the contest tab. There are no entry limits – the more you read, the more chances you have to win! On our guide you will also find information about our small team, suggestions for staycation reading, a few special events, and even our full list of club reads, both current and past. You can also vote for future book club selections!

The contest runs until July 25th, with winners announced on the 30th. Have fun and get reading!

From May 14 to June 15, we received 55 entries from 41 undergrads and 13 grad students who shared their favorite summer reads—thank you! 💛 ✨ Check out the winners and the Summer Book Recommendations on the Spring Wonderland Contest Guide.

Submit what you’re reading + your thoughts for a chance to win a Starbucks Gift Card!

The Dr. John Archer Library & Archives is pleased to host a health equity-focused visual art project from the Faculty of Nursing, “Photovoice for Health Equity.” In 2024, Dr. Shauna Davies, Dr. Coatlicue Sierra Rose, and Mr. Claudio Bezerra Azevedo Filho, of the Roots + Wires Research Collective, facilitated a Photovoice project focusing on the health and wellness needs of marginalized communities in Saskatchewan and how these needs may differ from the mainstream.

This project brought together a diverse group of 14 University of Regina undergraduate and graduate students who were asked to take photos from their daily lives speaking to the concerns of their respective Indigenous, Black, newcomer, 2S/LGBTQIA, and low socioeconomic status communities. This exhibition is a collection of the photos the students nominated as most representative of their collective concerns.

Photovoice for Health Equity Visual Art Exhibition Opening Reception

Dr. John Archer Library & Archives Archway Exhibition Space (LY 107.22)

Wednesday, June 18, 2025

6:00pm to 7:00pm

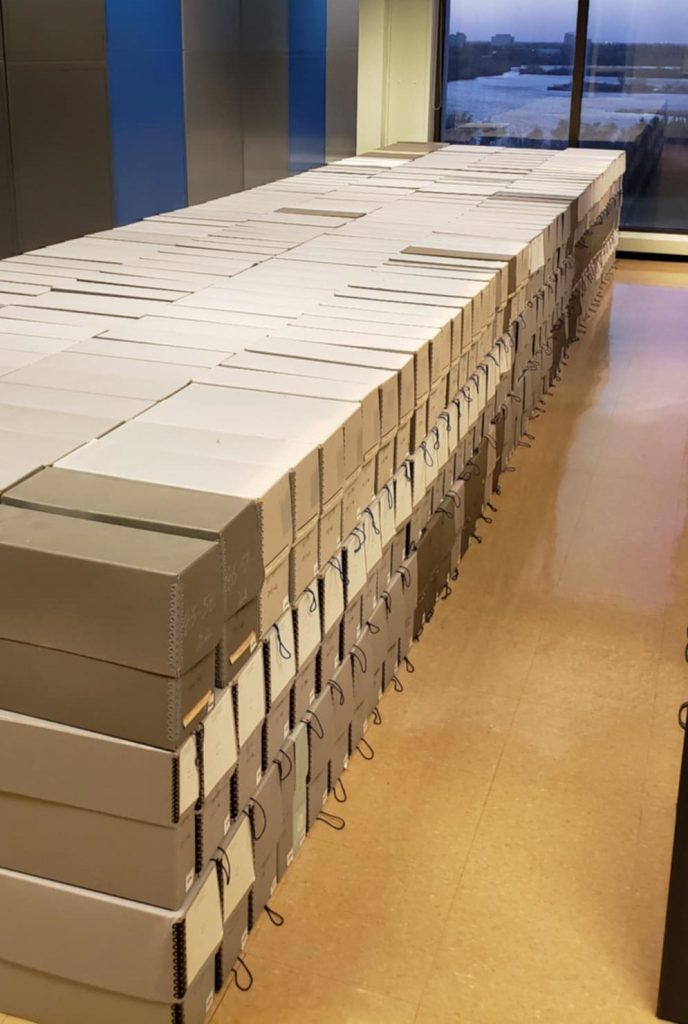

Renovations are underway in the main storage room of the

University Archives to help us to better preserve and provide access to our

collections. Special Collections materials are still accessible during the

renovations (we’ve moved hundreds of boxes upstairs, see photo 2) but there

will be retrieval delays for archival items still in the impacted space. Thank

you for your patience!