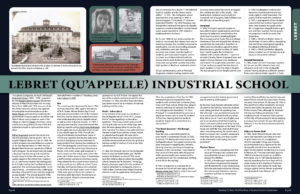

Lebret (Qu’Appelle) Indian Industrial Residential School

The Lebret (Qu’Appelle, St. Paul’s, Whitecalf) Industrial School, (1884 – 1998) , operated by the Roman Catholic Church (Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate and the Grey Nuns) from 1884 until 1973, was one of the first three industrial schools that opened following the recommendations of the Davin Report, and was fully funded by the government (Battleford was the other in what is now Saskatchewan). This school was located on the White Calf (Wa-Pii Moos-Toosis) Reserve, west of the village of Lebret on Treaty 4 land. Lebret school has a long history as one of the first industrial schools to open and the last to close.

Former Student Stories and More

Kerry Benjoe

Noel Starblanket

Lorna Rope | Where are the Children exhibit

Rita Watcheston | Where are the Children exhibit

Dillon Stonechild | Where are the Children

Wesley Keewatin

Joseph Martin Larocque “They scared us. From the time I was small ’til the time the, the priest, the nuns, the whole thing, they scared everybody with dead people, and, you know, talking about the devil. And, and they had this little chart, catechism, where here’s you’re going up this road, and the, the roads are winding like this, and the, the devil’s with a pitchfork. I was scared for a long time.304 (Survivors Speak p. 87)

Blair Stonechild

Ochankuga’he – (Daniel Kennedy)

Louise (Trottier) Moine

Andrew Gordon

Andrew Gordon’s daughter Edith claimed the nuns and priests were pestering her about her father being a pagan while she was ill with pneumonia. Andrew Gordon, believing it was their pestering that caused her death, requests the withdrawal of his other daughter.

Clive Linklater

Harold Greyeyes (as told by Jack Funk)

Audrey Redman (St. Paul’s Indian High School)

Greg Rainville

Documented Student Deaths: Valerie LeCaine , May 30, 1935, died of vomiting, after recovering from pneumonia in January and measles in March (Probably TB related); Victor Sugar, January 30, 1936, died of pulmonary TB at age 16; Evelyn Gordon, April 22, 1936, died of pneumonia. (Valerie Le Claire in records has been corrected to LeCaine by a family member)

Lloyd Brass

Big Change In Boarding Schools by: Lloyd Brass

January 1978 Saskatchewan Indian

Obit: https://leaderpost.remembering.ca/obituary/lloyd-brass-1065631212

Rick Pelletier

Gary Edwards

Seraphine Kay

Mike Pinay

Menu at Lebret School

Grey Nuns Archived Collection

Girls at Lebret

If These Hills Could Talk

Parental Resistance

Westwind Evening’s “Whisper in the Wind”

1923 Fire at Lebret/Qu’Appelle

Lebret Community Profile

Archdiocese of Regina: A History (Lebret)

Qu’Appelle Indian School marks 100 years Indian Record 47(4)

Photos

David Greyeyes-Steele

LEBRET, Sask. – June 7, 1953 will long be remembered by the students of Lebret Indian School, when six High School Graduates received their diplomas from the hands of Archbishop M. C. O’Neill, of Regina; the R.C.M.P. Band from Regina was providing the music.

Members of the graduation class were Linda Anaquod, Rose Alma Bellegarde, Clive Linklater, Herbert Strongeagle, Percy Mandy and Kenneth Goodwill.

The evening program featured R..c.M.P. band selections, numbers from the High School ‘and the girls chorus as well as piano and vocal solos. Archbishop O’Neill addressed

the graduates at the close of the commencement exercises. To the graduates we wish success and happiness.

Hazel Bitternose, who attended schools in Lestock and Qu’Appelle, Saskatchewan, said she enjoyed working in the priests’ dining room. “They had some good food there and I used to sneak some food and able to feed myself good there. So that’s why I liked to work there.”266 (Survivors Speak, p. 77)

Joseph Martin Larocque found religious education at the Qu’Appelle school frightening.

Joseph Martin Larocque found religious education at the Qu’Appelle school frightening.

They scared us. From the time I was small ’til the time the, the priest, the nuns, the whole thing, they scared everybody with dead people, and, you know, talking about the devil. And, and they had this little chart, catechism, where here’s you’re going up this road, and the, the roads are winding like this, and the, the devil’s with a pitchfork. I was scared for a long time.304 (Survivors Speak p. 87)

When she returned to the Qu’Appelle school after being sexually abused by a fellow student the year before, Shirley Brass decided to run away. She did not even bother to unpack her suitcase on the first day at the school.

I took it down to the laundry room and everybody was taking their suitcases down to wherever they kept them. I took my suitcase down. I told the nun, I said, “I have to do my laundry,” I said so I took it to the laundry room. I hid it there and that night this other girl was supposed to run away with me but everybody was going up to the dorm and I went and I asked her, “Are you coming with me?” And she said, “No, I’m staying.” So I said, “Well, I’m going.” So I left, went and got my suitcase and I sneaked out. I went by the lake. I stayed there for I don’t know how long. I walked by the lake and I sneaked through the little village of Lebret, stayed in a ditch. I saw the school truck passing twice and I just stayed there. I never went back. I hiked to—I had an aunt in Gordon’s Reserve so I went there. I had a brother who was living—a half-brother who was living with his grandparents in Gordon’s and he found me and somehow he got word to my mom and dad where I was and they came and got me. My dad wouldn’t send me back to Lebret so I went to school in Norquay, put myself back in Grade Ten. I didn’t think much of myself. I quit when I was [in] Grade Eleven in Norquay.463 Survivors Speak, pp. 133-134)

At the Qu’Appelle school, Raynie Tuckanow said, he witnessed staff committing sadistic acts of abuse.

But I know what they did. I know what they did to me and I know what they did to others, too. Looking up here, just like that up here, I watched the young man. They tied him. And I know him today, I see him today. They tied him by his ankles and they tied him to the [heat] register and they put him out the window with a broomstick handle shoved up his ass. And I witnessed that.548 (Survivors Speak, p. 154)