Crowstand Indian Residential School | Kamsack

Crowstand Indian Residential School | Kamsack

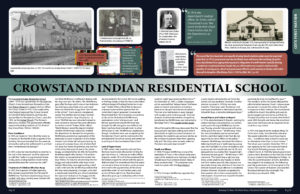

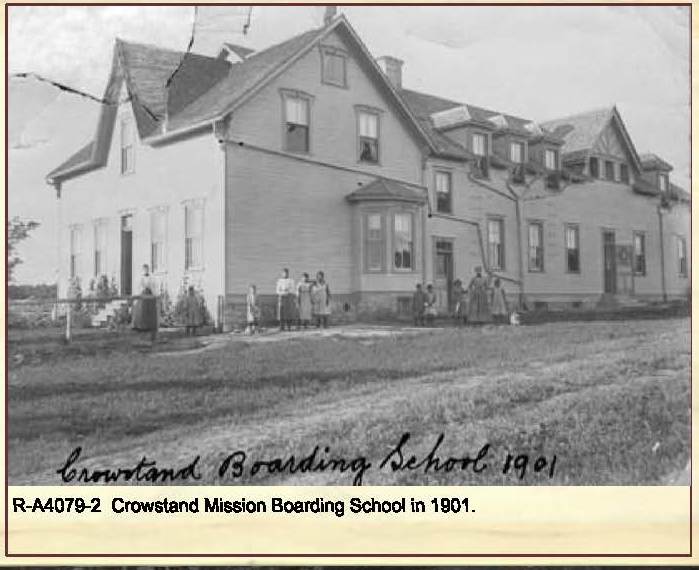

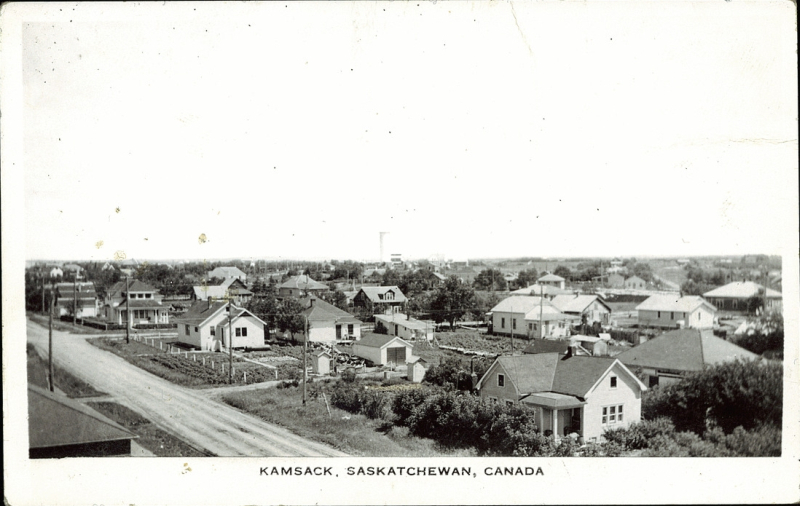

The Crowstand Indian Residential School (1889 – 1915) was operated by the Presbyterian Church. It was located near Kamsack on Cote First Nation Reserve on Treaty 4 land. The building was erected in 1899. When the school closed in 1915, it was replaced by Cote Federal Improved Day School in December 1916, located on Cote First Nation Reserve, and was also operated by the Presbyterian Church, and after 1925, by the United Church (The Women’s Missionary Society). The government officially approved boarding students at Cote Federal Day School from 1928 to 1939/40.

______________________________________________

In 1887, Rev. Geo. A. Laird (B.A. Dalhousie; B.A. in Theology, Manitoba College) was appointed to Fort Pelly reserves, which has since become known as Crowstand Mission. It was “during his regime a boarding school was established. It began by Mr. and Mrs. Laird taking some 8 or 10 Indian children into their own home during the severe weather of winter. From this self-denying and unremunerated beginning, the school grew until at one time it had as many as 55 pupils, but owing to transfers to Regina and other causes, this number has been reduce to about 30. Mr. Laird was succeeded in April, 1892, by the Rev. C. W. Whyte (B.A) who is assisted by his brother Mr. John S. Whyte as tade’s instructor, by Miss Kate Gillespie, as school teacher, and by Miss Flora Henderson, as matron (p. 18)”. Baird, Andrew Browning. The Indians of western Canada. Toronto: Press of the Canada Presbyterian, 1895 retrieved from http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/bibliography/2182/20.html

___________________________________

Staff Relations:

The Presbyterian school in Kamsack underwent a period of constant state of turmoil in the early twentieth century. Two days into her first week of teaching at the school in 1901, the new teacher, Miss Downing, informed Principal Neil Gilmour that, “on account of the children not being very healthy, the atmosphere of the class-room will not be such that she can stand it.”232 A week later, the matron, Miss Wright, also resigned. Gilmour strongly recommended that Wright’s resignation be accepted, since “she is certainly not the right person for the work.”233 Gilmour hoped to replace her with his cousin, a Miss Gilmour, who, in the past, had worked at both the Kamsack and Regina schools. However, Miss Gilmour initially turned the job down, saying she was glad to be rid of the “endless task of telling the same thing over and over again until my head used to get dizzy, and I would think, how much easier to do the work myself.”234

Gilmour was dismayed to learn that a former matron at the Regina industrial school, a Miss Nicoll, had been appointed as the new matron. He wrote that at Regina, “they have a cook, a baker, a laundress, a seamstress, and an assistant matron.” Therefore, the duties of a matron at Regina were those of a manager. At Kamsack, Nicoll not only would have to “understand how to make bread, but that she must do a larger share of the kneading of dough for 72 loaves of bread.” Does she know, he wrote, that “this is not merely an issuing of orders regarding the meals but doing the cooking herself and so with all the work?”235

It appears that Gilmour succeeded in discouraging Nicoll from taking the position. He also managed to convince his cousin to reconsider her initial rejection of the position, and she became matron at the end of 1901.236 It was Principal Gilmour who resigned by the end of 1902. Miss Gilmour, however, stayed.237 By 1911, she was acting principal. She appears to have been viewed as having made a positive contribution to an often-troubled school. In 1914, after she had retired, Indian agent W. G. Blewett wrote of the Presbyterian school in Kamsack, “Dormitories fair, play rooms dirty, water closets dirty. Many pupils dirty and poorly clad. Miss Gilmour’s retirement seems to have started it on the down grade.”238 Whether or not this was an accurate assessment, it is clear that a school’s success or failure was regularly laid at the principal’s door. (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, pp. 712-713)

Also read Denise Hildebrand’s thesis:

“At Crowstand I have found very warm and kind friends in Mr. and Mrs. Whyte. Mrs. Whyte keeps such a motherly eye on Miss Scott and me that it is never necessary for us to make her acquainted with the fact that we are feeling tired or sick, as she always sees it for herself. There are discouragements as well as encouragements connected with our labours here, but we share them with each other, and are all happy and hopeful (MIL, WFMS, WD, PCC, July 1894, Vol. 11 No. 3, letter by Miss Gillespie, dated 30 Apr 1894, p. 73).

Schools were understaffed and students unprotected (sexual abuse)

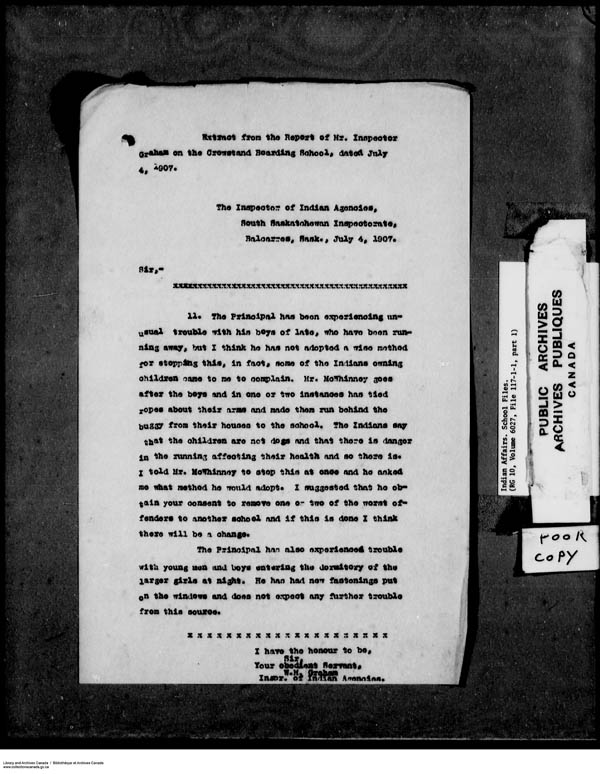

…the understaffed schools created the conditions for sexual relations that offended the morals of the churches and were beyond the oversight of the broader Aboriginal community. The schools also served as a setting for the sexual abuse of students by both staff and other students. Kamsack, Saskatchewan, Presbyterian school principal W. McWhinney’s 1907 comment to a church official is representative of church attitudes: “The Indian boy or girl you may know, yields easily to any impulse or desire and from twelve upwards their passions are peculiarly strong.”39 (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, p. 649)

However, parents understood that it was due to lack of supervision.

School officials could be reluctant to provide their superiors with reports on problems with sexual activity. It was only after the matter had already come to the attention of the local Indian agent that Kamsack school principal W. McWhinney told Presbyterian Church officials of how a group of young men, all former students of the school, had been caught with a bottle of whiskey in the girls’ dormitory in the summer of 1907.45 McWhinney wrote that he had refrained from reporting the matter earlier because of his “distaste for putting the disgraceful affair on paper.” In his letter, he explained that the problem was not new to the school. Prior to his being appointed principal in 1903, he said, a number of girls had been sneaking out of the school to meet with young men. These included former students of the Kamsack and Regina Presbyterian schools, one of whom was working as the school’s farm instructor. After he became principal, McWhinney discovered that, several times, the boys and girls had been visiting each other’s dormitories at night. Students were punished and the “windows were blocked so that they could only rise a short distance, while the stops were securely nailed on. The doors also were kept locked.”46 The problem recurred at the school in 1911 and 1914.47 In 1914, McWhinney argued that sexual relations between students were ongoing problems at all residential schools. “In our case these are always reported while in other schools the Agents there take the view that no good can come of reporting them.” He also returned to his argument that “Indian boys and girls have strong sexual passions.” He felt the “best remedy” would be “separate schools for boys and girls.”48 (The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, Vol. 1, pp. 649-650)

____________________________________________

Many educators, working in Native day schools, were frustrated by inconsistent school attendance. Kate Gillespie, a Presbyterian teacher in Saskatchewan described this challenge,

“… the attendance was irregular and not punctual and on bad days in order to secure anything like progress I had to walk up the road … go into [each] house, and hear and set lessons. In the afternoon return, correct exercises of the work, hear and set fresh lessons. The children could not come to school…I had to go to them.” Peter Bush. (2004). The Native Residential School System and the Presbyterian Church in Canada. Presbyterian History: A Newsletter of the Committee on History. The Presbyterian Church in Canada 48(1)

__________________________________________

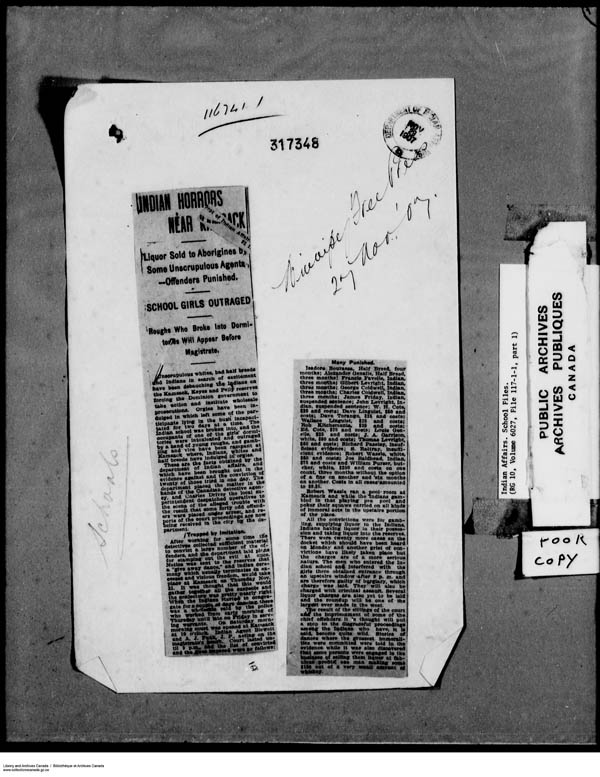

School Scandals

Inspector Report: Boys running away and being tied with ropes and break-ins to girls dorms

B’yauling Toni’s Moccasins of Remembrance Bike Tour Photos (August 8, 2021) in Kamsack https://my-site-102728-103753.square.site/byauling-toni. Toni writes of Crowstand IRS: “The site is on private farmland and I was unable to visit it. The exact location is unknown. It is suspected to have unmarked graves and Cote First Nations are in the process of gaining access to survey the site.”